Third in a three part series.

Whether or not the Northern Pass transmission line gets the state and federal permits it’s looking for, HydroQuebec is poised to send ever more of its hydro-power south. It’s increasingly clear that New England will need more power soon and with transmission lines are being proposed all around the Northeast, Canadian hydro is likely to play a role.

In just a couple of weeks, companies are scheduled to have a chance to bid for the right to supply electricity to New England in 2017, in something called the Forward Capacity Market. This auction’s job is to make sure the lights will stay on, three years out.

“What it does is really it’s a reliability market,” explains Dan Dolan, President of the New England Power Generators Association, which represents many power plant operators that bid into this auction. “It ensures there’s going to be enough power plants on the system three years from now to meet consumer demand.”

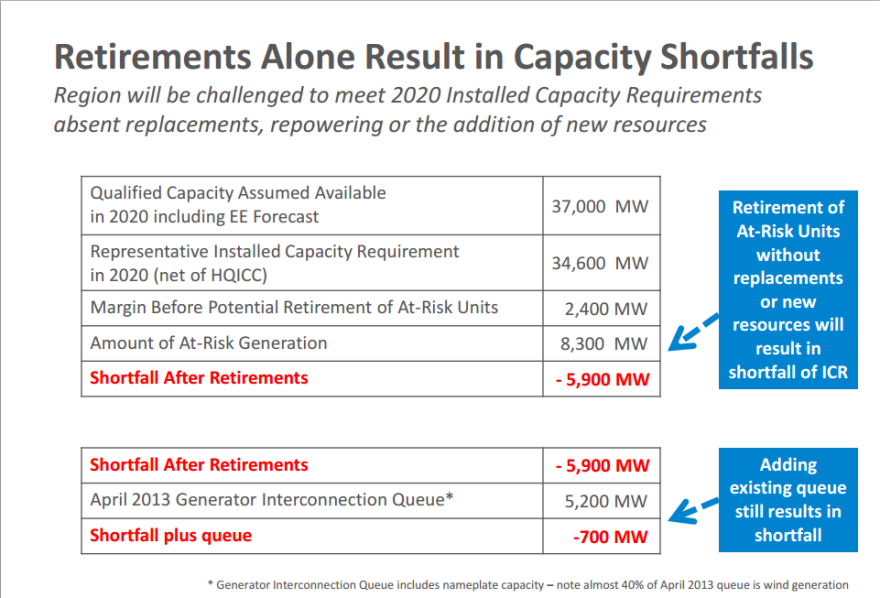

This year, for the first time in the market’s 8 year history, there might not be enough plants signed up to deliver in 2017.

“We’re seeing a transition away from some of the older generating stations, particular the coal and the oil facilities, where they do play an important role on the system but there have been a series of retirements taking place,” says Dolan.

The Vermont Yankee Nuclear Station will switch off at the end of this year, and Brayton Point – New England’s Largest coal plant – has announced it wants to shut down in 2017 (The grid operator, has asked it to stay online because of fears that the retirement could lead to blackouts, but the final decision rests with the plant’s operators)

At the same time, our neighbor to the North has got hydropower to spare, especially in summer. Most people in Quebec heat with electricity, so their grid is built up for really high use on the coldest days.

“There’s a lot of surplus energy in the summer that we can export,” says Hydroquebec spokesman Gary Sutherland.

Electricity prices in Quebec are pretty low, which means exporting boosts HydroQuebec’s profits. In 2012, exports – mostly to New England and New York – accounted for 15 percent of its sales volume, but 24 percent of its sales revenue.

“Working on those export markets is a really interesting part of our business,” explains Sutherland.

The head of the Northern Pass, PSNH’s Gary Long puts it another way. “They very much want to do business with us, in simple terms it takes transmission lines, and that’s been the difficulty.”

The trick about getting from where the hydro is to the demand in Boston and farther south: is what’s in between. “To get from Canada to New England,” says Long, counting off on his fingers, “New Hampshire, Vermont, or Maine.”

Here in New Hampshire, the Northern Pass has hit major opposition because of the impacts associated with the lines.

But not every proposal to move power South looks like the Northern Pass. Opponents have plenty of examples of proposed alternatives to point to: one to New York City buried under the Hudson River, another proposed in Vermont would be buried under Lake Champlain, and a third in Maine that would be buried along Maine’s highways.

PSNH has repeatedly said burying the line through New Hampshire would be prohibitively expensive, but critics are confident that if the utility backs down, someone will step up who is willing to bury the line.

“If that’s what it’s going to cost, it’s important that the developers know it’s going to cost that,” says Christophe Courchesne of the Conservation Law Foundation, one of the Northern Pass’ leading critics, “and if some of the developers lose some interest… my suspicion is that there are other developers who can make the spreadsheets work.”

And it’s all about spreadsheets these days.

“We made a decision in the 90s,” says Meredith Hatfield, New Hampshire’s Director of Energy and Planning, referring to the decision to move to a “deregulated” energy market, shifting the risks from bad market decisions by utilities from the rate-payers to investors. The hope of deregulation was that it would drive down costs.

“We were going to join a market and really try a market approach,” says Hatfield, “And if we feel like the market is not working, I think we have an obligation to try and fix it.”

If New Hampshire doesn’t like the projects the market is providing policy makers have to figure out how to change that. The conversation is underway right now about changing the states rules for siting new power plants, and adopting a new, non-binding state energy strategy.

“We really are at an interesting time where people are asking fundamental questions, and that’s a good thing,” says Hatfield, “When we did the last energy plan there really wasn’t this level of public interest in these issues.”

Whatever the conclusions, New Hampshire is going to have to decide how, if at all, it’s going to help the region replace its aging fleet of power plants, with or without Northern Pass and Hydro Quebec.