From now until Nov. 6, President Obama and GOP presidential candidate Mitt Romney will emphasize their differences. But the two men's lives actually coincide in a striking number of ways. In this installment of NPR's "Parallel Lives" series, a look at Obama's time at a Hawaii institution called Punahou.

Punahou School was founded by missionaries in 1841 — the campus is just up the hill from Waikiki, and it's built around a historic spring.

Punahou occupies a privileged position, not just on the hillside, but in Hawaii society. In his memoir, Dreams From My Father, Barack Obama recalled how his grandfather pulled strings to get him in.

"[F]or my grandparents, my admission into Punahou Academy heralded the start of something grand, an elevation in the family status that they took great pains to let everyone know," Obama wrote.

For generations, Punahou educated the children of plantation owners, businessmen and politicians. Pal Eldredge graduated from Punahou in the 1960s.

"In the beginning, we were known as the 'haole school,' " says Eldredge.

Haole is Hawaiian for foreigner — or white person. Eldredge says that when young Obama arrived as a fifth-grader in 1971, the school's complexion was just beginning to change.

"We didn't have a lot of African-Americans. So your first thing is, 'Oh, we've got an African-American. Terrific!' " says Eldredge.

He was teaching at Punahou at the time, and he remembers the future president as a pudgy, cheerful kid.

"He used to wear these shorts and striped T-shirts a lot, and sandals. But after you got to know him, not only was he a bright student, but he was just a funny, all-around kid, and everybody liked him," says Eldredge.

But in his memoir, Obama dwells on moments at Punahou when his race made him feel conspicuous, such as the time he was teased for playing with the only other black child in his grade.

"When I looked up, I saw a group of children, faceless before the glare of the sun, pointing down at us. 'Coretta has a boyfriend! Coretta has a boyfriend!' " Obama writes.

In the book, Obama's struggles with racial identity grow as he reaches high school, and he recalls intense discussions with another black student, an embittered boy he calls "Ray."

"Ray" is really Keith Kakugawa. He's part black, part Japanese.

Kakugawa says he and young Obama did have some heart-to-hearts about race but, in general, it wasn't a big issue at the school because Punahou kids had to stick together.

"Because we knew once we left that school, there was a target on our backs. No matter what race you are, you're Punahou. You're the rich, white kids. Period," Kakugawa says.

Of course, young Obama was not rich. He was a scholarship student. He worked at a Baskin-Robbins ice cream shop. It's still there, near the school. So is the apartment building where he lived with his grandparents.

In a way, Punahou was his neighborhood — and this being Hawaii, so was the beach.

Sandy Beach Park was one of his favorites. Surfer Turk Cazimero says the scene hasn't changed much since the '70s.

"You come down here on a weekend, you smell every type of weed there is," Cazimero says with a laugh.

Obama has admitted upfront that he did drugs in high school — that's in his memoir. But there are lingering questions about how much he did.

At Punahou, he and his buddies called themselves the "Choom Gang" — choom means smoke pot. And things sometimes got out of hand. One guy rolled a car. But his homeroom teacher, Eric Kusunoki, says he never saw signs of trouble. Young Obama's grades stayed good, as did his attitude.

"Every day when he'd come in, he'd always walk in the door very positive, very pleasant, big smile, you know, 'Hey, Mr. Kus, how you doing?' " says Kusunoki

Another school friend, Ronald Loui, says that when talking about the Choom Gang, you have to keep a sense of proportion.

"There was a group called the Stoners. And the Choom Gang wasn't the Stoners," Loui says.

The Choom Gang were the sons of successful people — one boy's father was a prominent judge — and there was an expectation that they would be successful, too. Loui says if you're looking for Punahou's lasting gift to Obama, this was it: The elite environment familiarized him with success.

"Everywhere he turned, he could see a path to leadership. The highest level of achievement is something he can touch — it's tangible," Loui says.

And it was during that Choom Gang period that young Obama took a class called "Law in Society," taught by attorney and Punahou alumnus Ian Mattoch.

"He was a student who appeared to be serious and yet he was able to socialize with all of his classmates, which isn't an easy thing to do at Punahou School," says Mattoch.

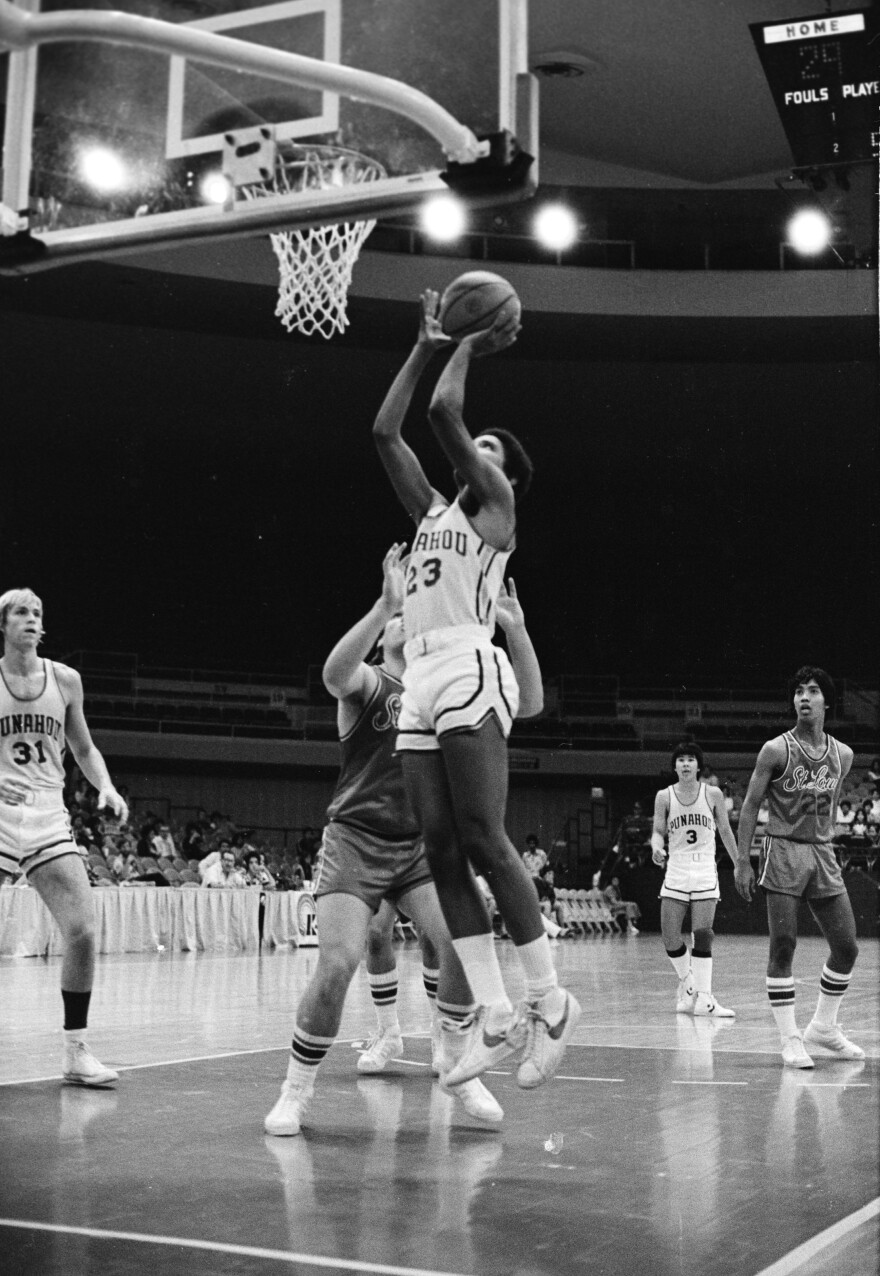

That may be an early glimpse of political skills — but he wasn't into politics yet. No student council meetings for him, perhaps because it would have meant less time for basketball.

"Basketball is his passion. He loved the game," says classmate Alan Lum. He played varsity with Obama. Today he teaches second grade. In high school, Lum says, if you were looking for the kid known as Barry Obama, the first place to check was always Punahou's outdoor courts.

"Just pickup games. That was his realm," Lum says.

Always shooting hoops — it's the one thing everyone remembers about him at Punahou. Another friend says that back then, if he'd had to guess, he would've predicted Obama was destined for a bright career — as a basketball coach.

On Weekend Edition Sunday, Don Gonyea will report on Mitt Romney's years at Cranbrook prep school in Michigan.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.