A new technology holds the promise of treatment for the nearly one million Americans with epilepsy that don’t respond to medications. The FDA has approved a new implant that uses bursts of electricity to stop seizures before they start.

That’s good news for people like Chrissy Goodman. She’s 32, from Concord, and had her first seizure at age 14.

Epilepsy has affected every aspect of her life, from where she can live to relationships to education.

“I dropped out of high school, I was having many seizures at school, and just getting picked on for it, and I just decided to get my GED,” says Goodman.

She’s held positions, including as a secretary, cashier, and in food service, but seizures at work and on the bus on the way to work derailed employment.

Like roughly 30% of people with epilepsy, medications failed to help Goodman, and surgery to remove the portion of her brain where the seizures originate was ruled out as too risky.

Goodman says it’s all been tough on Madeline, her 10-year old daughter.

“When I was having seizures before I had the surgery, I remember you would cry and go get Aunt Becky or Uncle Bob or Grammy or whoever we were with. I know you were very traumatized,” says Goodman.

“I just don’t remember,” says Madeline.

Surgery, And Fewer Seizures

She does remember her mom’s trip to the hospital in 2007, and can quickly part Chrissy’s straight brown hair to reveal the scar.

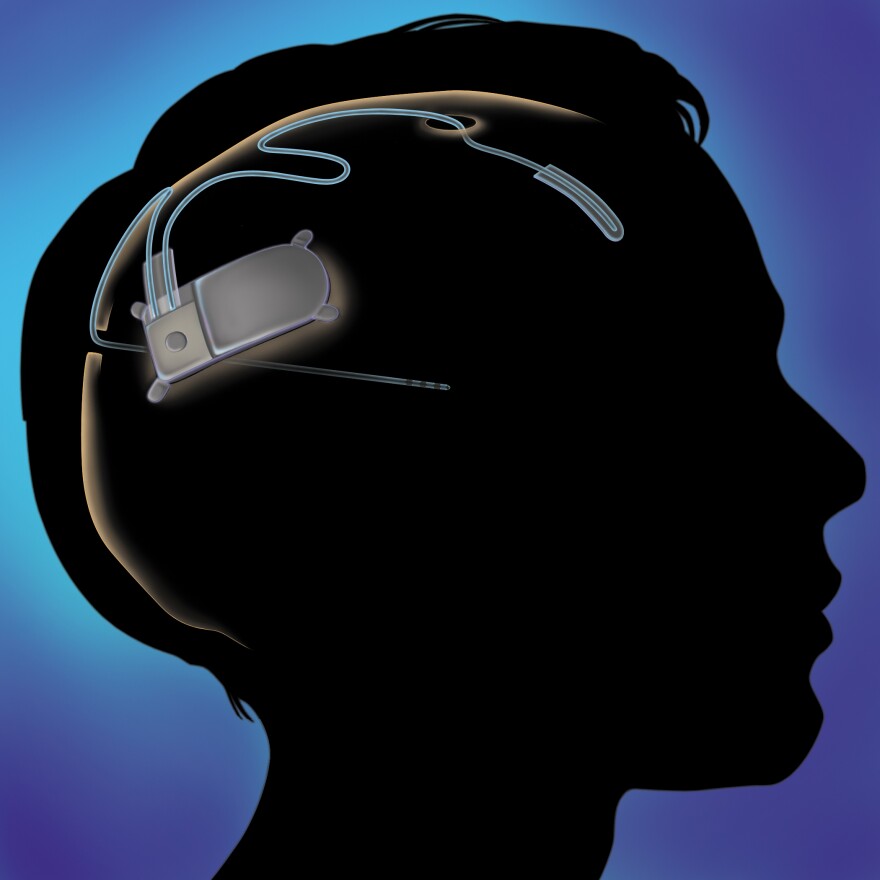

As part of a multi-year clinical trial, Goodman had a device implanted into her skull. It’s slightly larger than a matchbox, with thin wires snaking out that burrow into the areas of the brain where her nerve cells commonly misfire.

This RNS Stimulator is constantly checking for irregularities, and then when it detects something wrong, shooop, it sends a burst of stimulation through the wires.

“We believe that we could disrupt that abnormal activity and prevent it from spreading through the brain and therefore eliminate some seizures,” says Fred Fisher, CEO of Neuropace, a Silicon Valley start-up backed by $215 million in venture capital.

He says the responsive technology is a step forward from what’s available today. Something called the Vagus Nerve Stimulator has been in use since the late 1990’s. It gets implanted in the chest and uses an on-again-off-again pulse.

Neuropace is smarter, as it can be more finely tuned to the flaws in a patient’s brain.

“I think this is a huge advancement and a huge step in the right direction to develop treatment therapies that are specific to patients, and patients’ brains,” says Dr. Barbara Jobst, who runs the Dartmouth Epiliepsy Center and was part of clinical trials.

An Ongoing Treatment

Once a week from her home, Goodman holds what looks like the handset of an old landline telephone right up to her head. The wand communicates with the device, and then transfers data that Dr. Jobst can look over. She can then tweak the stimulator’s settings—without surgery—as needed.

More than half of patients in the Neuropace trial saw more than a 50% reduction in seizures. Results for Goodman were also positive: she can now go months at a time without one.

“And hopefully things will progress, maybe I’ll get a job, if I go 6 months I can drive, and maybe we’ll get a place of our own someday. But little steps at a time,” says Goodman.

Neuropace is ready to take a big step.

Right now, only five hospitals around the country including Dartmouth offer the procedure. By the end of this year, the company hopes to grow that number ten-fold.