Ten years ago this month, the monster storm Hurricane Katrina thundered through New Orleans and coastal Mississippi and Alabama. Many who survived the storm and its aftermath are still feeling its terrible impact.

This week on For the Record: Hurricane Katrina's mark on one family, 10 years later.

In 2005, sisters Regina and Talitha Halley had just moved out of the Lower Ninth Ward in New Orleans into a new house on Spain Street. Regina, now 33, took care of her sister full time while their mom worked as a professional caregiver.

In the days leading up to the storm, Regina had been paying attention to the news. When the weather alerts turned serious, the girls got worried. Their mother was at work and the family didn't have a car.

Regina stayed glued to the television.

"The mayor [Ray Nagin] came on and said ... 'If you have nowhere to go, you can come to the Superdome.' "

When their mom finally got home, Talitha says, they packed up a few things and left for the Superdome.

"I thought that it was kind of a big deal, but that we'd be able to go home maybe in a couple of days," she remembers.

They found a city bus that was headed to the Superdome and they got on, hoping they were moving toward safety.

But the scene when they arrived was overwhelming. Thousands were lined up outside. Talitha, Regina and their mom waited for seven hours before they finally got inside.

While the desperation was visible everywhere, Talitha, then 12, didn't see it.

"I felt like it was a big party in the beginning," she says. "My friends were there, and my brother's friends and my sister's friend were there, people from my neighborhood that I've grown up around, been around them my entire life."

It's one of many things Regina remembers differently.

"You know, you got to see a few people you know, and it was OK," she says. "By, let's say 2 o'clock in the morning, it was a third-world country."

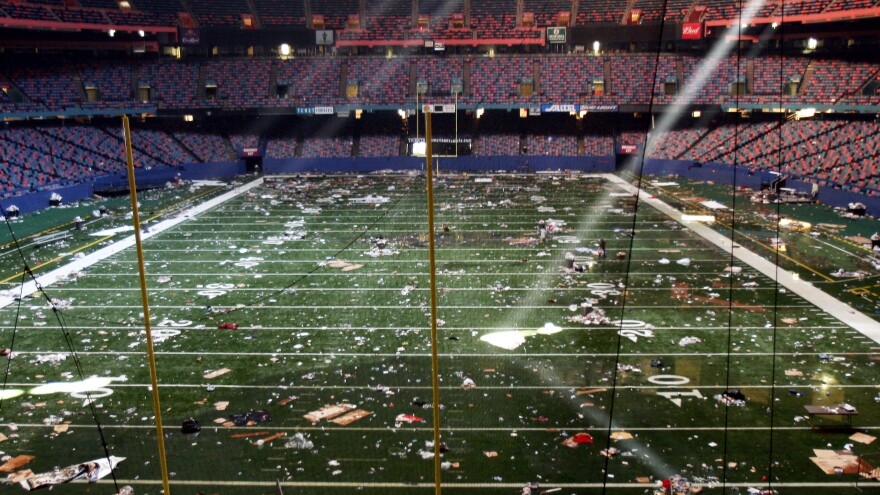

Tens of thousands packed into the sweltering corridors and arena seats of the Superdome, eating MREs and waiting to go home. The girls' mother clicked into survival mode, especially when the storm ended and people thought they'd be able to leave.

She became obsessed with finding a way out, and eventually, Regina says, her mom started to lose her grip on reality.

"She would come wake us up out of our sleep and tell us, 'Come on, come on, let's go get into the line, they say the bus is coming! Come on, come on, let's go, let's go!' And I said, 'Mom, no bus is ... coming.' "

Regina felt it was up to her to get them through. Days passed and conditions inside the Superdome deteriorated. Talitha remembers small pieces of the ceiling falling on her. Going to the restrooms was nauseating.

"If you could imagine, even after a few hours at a football game or a basketball game, or even a concert, restrooms are horrific by the end of a night," she says. "So could you imagine that for seven days?"

Regina remembers the sinks in the restrooms — the kind with big bowls that a lot of people can use at the same time. She remembers one particular trip to the restroom with Talitha.

"When we got ready to get to the bowl, they have two children in the bowl. Their ages had to be between 3 and 5. It was a little boy and a little girl, and they were face-down. 'They can't be alive,' " she thought. "So, we ran out the bathroom, and they had a guard that was standing, I want to say, about maybe 20 feet away. And I told him, 'Hey, they got two children that's in the bowl in the bathroom!' He said OK.

"So, me and Talitha, she's looking like, 'That's all you going to say is OK?" Regina continues. "So I told him again, I said, 'Maybe I'm not explaining it right. There are two children face-down in a pool of water in the bathroom.' It took them three days to come get those kids."

Here, again, the sisters' memories diverge. Talitha doesn't remember two children face-down in the bathroom.

The chaos that unfolded in the Superdome was widely reported. Conditions were horrible, the experience traumatic. But 10 years later, it's still hard to determine exactly how many people died there.

Accounts vary. In surveying half a dozen different reports, NPR found the number ranges between six and 10. It's impossible to verify Regina's story about the two children, and NPR couldn't find any reference to children in the reports.

But there is no doubt that Regina Halley believes that is exactly what she saw, and it has haunted her ever since.

What Talitha remembers is getting out. After seven days in the Superdome, the buses finally came.

"And everybody was just — you could see a sense of relief, but so much pain and kind of, a lot of people just in shock," she says.

They arrived in Houston. Volunteers were there to help. They were given food and clothes.

"I remember just feeling clean," Talitha says. "We hadn't even taken showers, but just the feeling of being able to put on fresh underwear, and a new change of clothes. It was everything in that moment."

The Halleys had a relative in Houston, so they had a home until they figured things out. They knew they weren't going back to New Orleans, so Talitha got settled into middle school.

"And I was like, 'OK, this is not so bad,' " she says. "That's when I realized that it would've been OK. That the new life was going to be fine."

That's not how Regina felt.

"I still don't feel like I'm OK," she says. "Like, for us, tomorrow never came. We were supposed to go back to our house. My sister was able to push through ... I don't even know how she was able to cope with it as a child, or maybe her coping was to move forward and not let it stop her. But in me and my mom's case, it's totally different.

"To this day, if it's raining, my mom, she still packs a suitcase," Regina continues. "She goes through the cabinets and gets all her canned food, and puts it in her suitcase, and she sits it by the door."

Regina still lives in Houston with her mom, but she's not happy there. She's training to become a barber and sees a therapist to work through the trauma she suffered during the storm.

Talitha thrived. She did well in school and graduated from Howard University this spring. Last week, she moved to Baltimore to start a new job. She says she doesn't talk about Katrina much with her mother and sister.

"Never in depth," she says. "There are small conversations, but it's never, 'Let's have this big conversation about how we feel and where we think we're going,' and different things like that. It's a touchy topic."

"Me and her have our little bits and pieces," says Regina. "As far as in her talking about the stay in the Superdome, and all that different stuff, she don't talk about that. Maybe she goes through it on her own, but I think she just kind of blocks it out. And maybe that's a good thing for her, because she's stronger than I am now."

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.