A mid-summer Saturday afternoon should, by normal standards, be a sleepy time in New Hampshire politics. The presidential primary is months in the rearview mirror. The state elections are just revving up, and the Legislature has left town for the year.

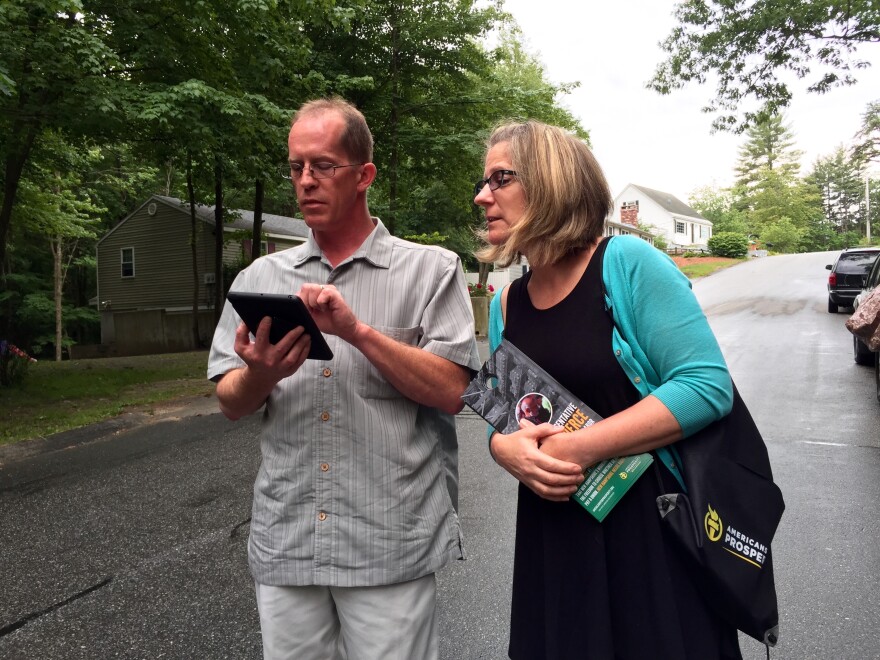

So why were John and Laura Spottiswood loading up the family van to go canvassing in Goffstown?

The Pelham couple has been involved in local Republican committees, and they’ve campaigned for GOP candidates in the past. But, increasingly, they’re turning to a different outlet for their political activism, and it's one most New Hampshire voters know little about: Americans for Prosperity.

The wide-reaching conservative advocacy network, backed by business moguls and mega-donors Charles and David Koch, pushes for “lower taxes, less government regulation and economic prosperity for all.”

But since it launched in New Hampshire eight years ago, the local arm of AFP has grown into a de facto third party in state politics. It recruits and trains volunteers, canvasses heavily around state elections, injects itself into local policy fights and has otherwise managed to build a grassroots infrastructure that now rivals the state Republican Party's.

“They’ve helped elect some people in Concord. They’ve also caused trouble for others,” says Ryan Williams, former communications director for the New Hampshire Republican Party. “They’re definitely a force that people have recognized during their time in New Hampshire.”

But while its positions are fiscally conservative, the group brands itself as nonpartisan: “It’s not about who sits in the seat,” says Greg Moore, AFP’s New Hampshire Director, “it’s what comes out of the policy pipeline in the process.”

That branding is part of what's helped AFP build a local following that covers the conservative end of the ideological spectrum. The crowds showing up to its events include seasoned Republican operatives and politicians, but also members of the libertarian “Free State Project” and twenty-something activists who say they don’t fit into either party.

AFP’s constant presence in New Hampshire also helps to further its rapport with local activists — who it relies on, in turn, to power much of its work on the ground here. Even though it’s just one arm of a much larger political advocacy network, to Laura Spottiswood, it “feels like they have roots here.”

“There’s always an issue, too, to be involved with. That’s fun, too,” John added. “It’s a never-ending cycle, and it just keeps bringing more and more people in.”

Building an organization, behind the scenes

Earlier this year, AFP expanded beyond its Manchester headquarters to open field offices in Dover and Nashua, where it holds regular phone banks. It has 10 paid staffers, Moore said, and counts about 44,000 volunteers across the state.

It puts those volunteers to use in a number of ways: get-out-the-vote campaigns (it was involved in each of the last five legislative special elections), phone banks meant to drum up public pressure against state lawmakers around a particular issue, and even the occasional tax dispute at the local level. Last fall, it held a series of phone banks around a special election over the Derry budget, and later did the same when Dover was weighing whether to override its tax cap.

But as its political presence grows, much of AFP’s inner-workings remain out of sight. That’s because, unlike actual political parties, AFP doesn’t have to tell the public how it raises and spends its money in New Hampshire, and it doesn’t have to follow the same rules as other political committees.

(For more details on what AFP does have to report, and what kind of oversight it's subject to: What We Know About Americans for Prosperity in New Hampshire)

While special interest groups aren’t new in New Hampshire politics, AFP stands apart for its ability to carry out all of the major tasks associated with a traditional political campaign and the strength of its voice, particularly among lawmakers on the right.

Each year, it mails out pledges to all candidates running for state office — its planks include a commitment to pass Right-to-Work legislation and to oppose all forms of the Affordable Care Act in New Hampshire.

This year, Moore says about 110 signed pledges were returned within the first week. And when the Republican candidates for governor met for their inaugural debate of the primary campaign, one of the first questions they had to answer was whether they would commit to signing.

New Hampshire Republican Party Vice Chairman Matt Mayberry says AFP has also had a more subtle effect on the political scene: Their full-throated, instant pushback leaves less room for nuance during high-profile debates.

“If you vote a certain way and you do it for whatever reason you do it, outside groups are jumping down right away: You voted this way, why did you vote that way? There’s an instant accountability,” Mayberry says.

A delicate dance with the "Establishment"

AFP has at times complicated things for the state’s Republican establishment. For one, Republicans say, people wrongly assume that the organization is just another arm of the state GOP. At one recent event, Mayberry recalls, a new candidate for state representative spoke up to ask: “When is AFP going to go knock on doors for me?“

In reality, Mayberry says the two groups have two distinct, and sometimes competing, missions: The state party is there to support and elect Republican candidates of all stripes; AFP is there to advance a set of specific ideals, and sometimes that means taking aim at Republican candidates who don’t align with its views.

For one example, look no further than AFP's response after the Legislature voted to extend the state’s Medicaid expansion, which the group opposes. AFP held a series of “Accountability Phone Banks” and door-knocking campaigns targeting the officials who voted against it — including longtime Republican Sens. Nancy Stiles and David Boutin. Both have since announced plans to step away from their seats.

In its early years, under the leadership of one-time Donald Trump campaign manager Corey Lewandowski, New Hampshire’s AFP chapter earned more of a reputation for publicity stunts than policy clout. There were Lewandowski’s staged debate with a cardboard cutout of then- Gov. John Lynch, for instance.

Moore took over as AFP’s state director in 2013, but before that he worked for years in and around state government: former chief of staff to the Speaker of the House; legislative policy director; advisor to the state health commissioner. These days, you’re more likely to see him sitting in on committee hearings than debating a cardboard cutout to advance AFP’s goals.

Untangling the group’s direct influence on policy can be complicated, both because of the opaqueness of its finances and the complicated nature of the legislative process. Still, AFP has taken credit for helping to sway the outcome of a number of recent high-profile policy battles: The inclusion of business tax cuts in last year’s state budget and the cuts to the state budget enacted during the 2011-12 session, for example.

'They've ingratiated themselves and integrated themselves into the political society.'

AFP also publicly tracks its own successes through an annual “Legislative Score Card.” This year’s edition identifies a dozen specific votes on the House side used to assess which lawmakers were most in line with its priorities.

In that chamber, the group’s preferred position prevailed in eight of those cases: stripping funding for a passenger rail study, killing efforts to create a new capital gains tax and stopping a measure that would allow local communities to increase the rooms and meals tax, for example.

Its effort to halt the state’s Medicaid expansion or to advance Right-to-Work legislation, on the other hand, fell short – but that hasn’t stopped the group from calling out lawmakers who didn’t vote the way it wanted them to.

Despite its varying level of success on a policy level, AFP’s ability to work state politics from the inside has nonetheless allowed it to establish a level of authority that sets it apart from other third-party groups around the Statehouse, Mayberry says.

“They’ve ingratiated themselves and integrated themselves into the political society,” Mayberry says. “They do make a difference. When they’re standing in the hallways of Concord saying to a state rep, ‘Are you going to vote on this?’ There’s some accountability there. “

Case in point: When the Spottiswoods were knocking on doors in Goffstown a few weeks back, they were handing out fliers targeting state Rep. David Pierce, a Republican, over a vote he took on a recent “Right-to-Work” bill.

One of the doors on the couple’s route belonged to another lawmaker, Rep. John Burt. The third-term Republican assured the canvassers that he was a “huge supporter of Right-to-Work.” On this and other issues, Burt said lawmakers have learned that, if they oppose AFP, they’ll have to answer for it.

“This is important,” Burt told the Spottiswoods, holding up the flier targeting his colleague. “New reps that are coming up, they’re saying, 'Oh, that's what happens.' And I said, 'Yeah, misbehave, and you’re going to get one of these.' ”

AFP is able to send this kind of message to New Hampshire lawmakers thanks in part to the size of the local legislative districts — where swaying a small number of votes could unseat a state representative — but also thanks to the state’s shifting media landscape.

Where newspapers used to routinely print recaps of how individual local legislators voted on key issues, Moore says the shrinking Statehouse press corps has made it easier for groups like his to push their own information directly to voters.

“The way the media’s changing and evolving has created a vacuum,” Moore says. “And part of what we’re trying to do is trying to fill that vacuum so that the public has an awareness of how their elected officials are voting on important issues.”

To understand why this outside organization spends its time taking umbrage with one state representative’s vote on a single bill, it’s worth remembering that New Hampshire is just one piece of a much larger effort by Americans for Prosperity to change policies across the country from the ground up. The Koch network reportedly has more than 1,200 employees in 38 states, and the staffs of AFP and other Koch-backed groups grew by 50 percent in 2015.

A critical part of that effort is investing not just in fliers or advertisements, but in volunteers like the Spottiswoods. One way AFP does that is by holding a recurring "Grassroots Leadership Academy" — a free, six-week advocacy training course — and by sending local volunteers on all-expenses-paid trips to its national conferences, where they can receive more training from AFP.

In most of the group’s policy battles, over tax caps or Medicaid, volunteers amplify AFP's ability to push back on lawmakers: They can call a state representative to complain (or praise) their vote, they can canvass and collect voter data to guide future campaigns, and they can help to shape the public conversation in their communities around a particular issue that AFP might want to elevate.

Sending volunteers out to knock on people’s doors and talk about Right-to-Work laws, for example, is just one step in AFP’s long-term goal of keeping that issue on the radar for the upcoming legislative session.

“Part of this effort that we’re focusing on right now, as far as Right-to-Work, is an opportunity to have a conversation with the public, at the door, on the phone, but also to make the Right-to-Work issue an important one this year,” Moore says. “So that as we enter the 2017 session people say that they’ve had a chance to understand the issue, they know what the issue is.”

AFP has already taken credit for pushing other state legislatures across the country to pass this kind of legislation. If things go according to plan, Moore says, their goal is make sure that New Hampshire becomes the 27th Right-to-Work state next year.