It was a quiet summer night in June when EMTs in Laconia got the call of a possible overdose at a nearby house.

When they arrived, they were brought to a bedroom with posters on the wall, laundry spread on the floor and a snowboard laid up against a dresser.

A 29-year-old man was lying on the ground not breathing, after overdosing on Oxycontin and fentanyl. He was wearing pastel board shorts and a t-shirt that accentuated his muscles.

Once inside, they got right to work, at first giving him a nasal dose of Narcan. But when his heart rate and breathing did not increase, EMTs gave him Narcan through an IV, causing him to regain consciousness in a matter of seconds.

Since the late 1990s, New Hampshire has seen a 500 percent increase in overdose deaths, to 325 in 2014, more than triple the number of traffic deaths. A third of those deaths were caused by opioids. Last year Narcan was given roughly 1,921 times statewide. The state reached almost half that number in just the first four months of 2015.

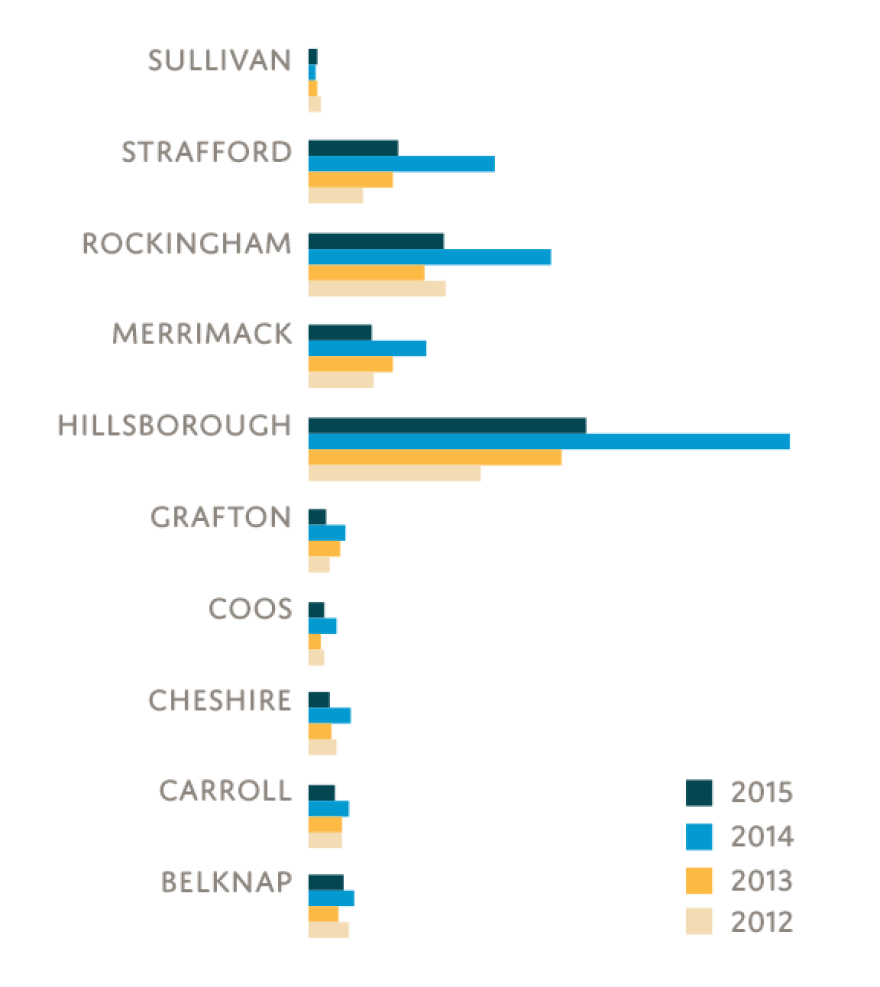

NH Town Map: Per Capita Narcan Cases 2012-2015

“It’s absolutely a lifesaving tool that if we get there in time, Narcan almost instantly reverses whatever they are overdosing on, if it is a narcotic based drug like that," says Lt. Jason Bean with the Laconia Fire Department, who adds that in Laconia, Narcan has been used more than 60 times since January. "And it’s probably one of the more important drugs we are carrying now, especially with this epidemic.”

That’s why lawmakers and the governor supported legislation this year to get Narcan to more people including police officers, family and friends and even addicts.

But, so far the rollout has been slow.

Despite reducing the hours of training officers who carry Narcan are required to complete from 100 to eight, only half a dozen departments are in the process of getting officers certified.

New Hampshire is now one of the 39 states and Washington D.C. that allows friends and family of addicts to get prescriptions for Narcan. And federal lawmakers are working to expand access nationwide.

Bob Stout with the state’s Board of Pharmacy says the bill’s simplicity has caused some confusion.

“The problem that we have in the early stages here is just the lack of clarity in the bill around how dispensing will go, limitations and proper training for people,” Stout says, adding that until the specifics are cleared up it will take time for physicians and pharmacists to feel comfortable prescribing it.

Seddon Savage, director of the Dartmouth Center on Addiction, Recovery and Education, says doctors may be wary of prescribing Narcan because of the broad terms of the new law.

"The wording is, 'in good faith with reasonable care,'" Savage says. "So, what is good faith and reasonable care in this kind of setting? Do you have to have a doctor-patient relationship? Or can I, as a physician, write a prescription for somebody in the street that I see that looks like they're using opioids?"

Narcan, which is not addictive and cannot be used to get high, has been used in emergency rooms since the 1960s. But Lt. Bean said it’s only recently become a necessary tool for first responders.

“It was always one of those medications that we used occasionally, but then we would have to replace it when it expired because we never used it," he says. "Now we are to the point where the stuff we have on the trucks aren’t expiring because we use it so much."

Narcan works by binding to receptors in the brain, blocking the opioid from causing respiratory arrest. Depending on how many drugs a person takes, an overdose can stop a person from breathing in a matter of minutes.

And because some opioids, including heroin, are now being laced with fentanyl, a more potent and dangerous narcotic, first responders often have to double their doses of Narcan. Lakes Region General Hospital, where the 29-year-old Laconia man who overdosed was transported, has tripled its supply of Narcan this year.

Studies show for every drug-related death there are nine survived overdoses, and the expanded use of Narcan is expected to increase the survival rate.

Kathy King’s son is one of those Narcan success stories. Her son, who is in his 20s, is now in recovery from heroin, but she’s still haunted by his close call.

“When they are using Narcan, they are bringing people back. If they do not have Narcan on their truck or in their police car, these people are not living, they’re dying,” said King of Rochester.

Donna Marston of Concord has a 32-year-old son in long-term recovery. She says to her knowledge, Narcan was never used on her son, but said when he was using, having Narcan around gave her a sense of security.

“Can you imagine walking into your child’s bedroom and he or she is unresponsive," she says. "And then having to call the ambulance and having to wait, depending on where you live, it could be four minutes it could be 10 minutes for them to get there. How would you feel if your child passed and you’re standing there watching your child die?"

Marston now runs a support group and is working to help families gain access to Narcan, which is relatively inexpensive.

A nasal kit cost $30 to $40. Many insurance companies include the drug on their formularies, depending on the policy. New Hampshire's Medicaid program covers patients on a case by case basis, officials say, but the state is not required to pay for it. For people without insurance, the cost of the kit falls to the ambulance company that responded to the overdose.

As demand for Narcan increases the cost may go up. That's what happened in both Massachusetts and Rhode Island after they passed similar laws.

At Concord Hospital, the price of Narcan has almost doubled from $13 a dose to $28 in the past year, says pharmacist David DePiero, who expects the cost to continue to go up once the new law is fully implemented.

Only one pharmaceutical company manufactures Narcan in the dosage that is used as a nasal spray. Jason Shandell, the president of Amphastar Pharmaceuticals, declined to address the company’s pricing, but says “manufacturing costs have increased on an annual basis.”

More recently the FDA approved Evzio, an injectable form of naloxone that comes with electronic-voice directed instructions. An Evzio kit can cost as much as $700.

Support group leader John Burns urges parents, spouses and friends to get Narcan in whatever form they can afford.

His 18-year-old daughter was saved by Narcan after overdosing on heroin last year. He now runs support groups in Dover and Rochester and has been working to get dozens of families access to Narcan. But he’s worried not enough people know about it. He says many of the doctors he has called across the state are not yet informed of the new law.

“You know heroin is almost looked at as more of a law enforcement than a healthcare issue, and this is a prime example of it, with the healthcare community isn’t even aware of an important law like access to the public for Narcan, let alone trained or understanding it,” Burns said.

The state's new law allows the use of standing orders. That means a doctor can authorize Narcan prescriptions for anyone who says they’re at risk of an overdose or has a friend or family member who is. Under this measure, third party organizations such as drug treatment centers and NGOs can also store and distribute Narcan.

The Attorney General's office is working with the Board of Medicine, various state agencies, as well as pharmacies such as Walgreens, on crafting prescribing protocol and training under the new law, something that could take two to three months.

But as promising as Narcan is, it doesn’t cure addiction.

Justin Younger is 31 years old and lives at a treatment center in Dover. Younger, who has been clean of heroin for more than a year now, says he was saved by Narcan multiple times.

“I literally like left the hospital and went to my friend’s house who is a dealer right away and grabbed some more," he says. "Like that didn’t even faze me, like almost dying didn’t even faze me. It’s kind of insane when you really think about it."

But Burns says Narcan buys more people more time – more time to seek treatment for addiciton.

“Narcan is not the end all be all. There are people who don’t seek recovery after," he says. "But there is a lot of people that do, and if they are not here, we can’t get them treatment, so why not use this tool and give them a shot to find recovery like my daughter did.”

And advocates say that, for some people, that second chance could make all the difference.