New analysis of state and county-wide data shows black and Hispanic people are arrested and incarcerated at higher rates in New Hampshire than whites are, and at more disproportionate rates than blacks and Hispanics nationwide.

Blacks and Hispanics make up less than 5 percent of New Hampshire’s population, but account for 9 percent of the state’s arrests. That racial disparity increases when you look at the jail population in New Hampshire.

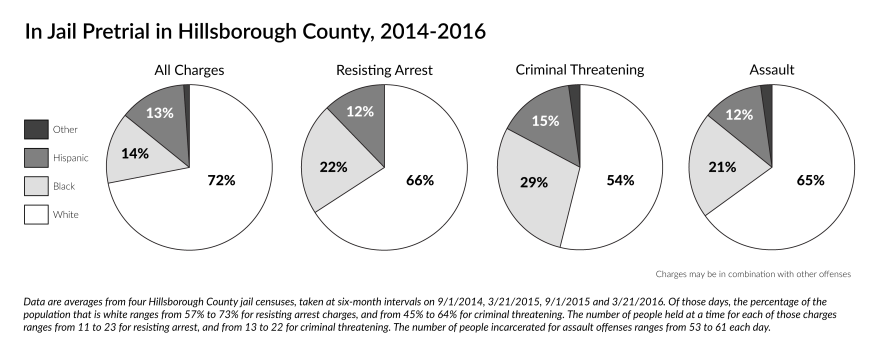

For example, drug crimes are the most common type of offense for which people end up at the Hillsborough County jail. While whites make up 83 percent of those arrested for drug offenses in the county, they are only 69 percent of those incarcerated while awaiting trial.

Disparities in New Hampshire's criminal justice system are especially notable for black people.

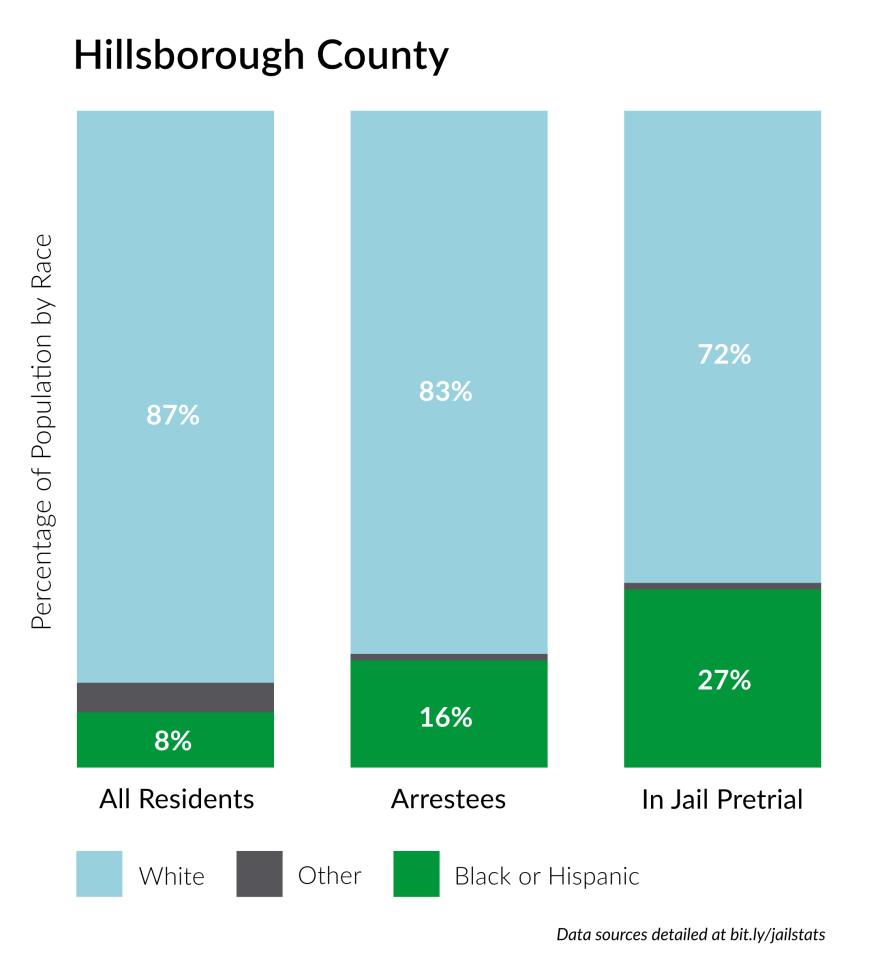

Nationally, blacks are 3.5 times more likely to be in jail than whites. In New Hampshire, blacks are 5 times more likely to be in jail, and in Hillsborough County – the most populous and diverse county in the state – they are nearly 6 times more likely to be in jail than whites.

Little research has been done in New Hampshire around race and the state's 10 county jails, which are run by county governments. No comprehensive data is available regarding these jails’ populations.

But data provided to NHPR by the Valley Street Jail in Hillsborough County allows a glimpse into the details of who is incarcerated here, and why.

Read: How We Crunched the Numbers

Manchester Police Chief Nick Willard said he plans to analyze his department’s arrests by census tract, to better understand the disproportionate arrest rates in Manchester. He says he has questions like “what types of arrests are being made? Who are the victims? Who’s reporting it? Is it a police officer making a car stop and doing it of his own productivity? Or is it a victim calling to make a report?”

When first presented with data indicating disparate arrest rates in Hillsborough County, Willard suggested offenses committed in Manchester by people of color from across the Massachusetts border were skewing the data. He provided NHPR with his department’s arrest data, which includes offenders’ city of residence. That data, from 2014, shows black residents of Manchester are three times more likely to be arrested than white residents: a more disparate rate for blacks from Manchester than overall in Hillsborough County.

Putting the numbers in context

This data comes in the midst of national strife around criminal justice and minority communities. Although cities in New Hampshire have not been in the national spotlight for police conduct, the data indicates that the state’s criminal justice system contains inequities that are similar to those in communities nationwide.

Woullard Lett, a former police commissioner in Manchester and the city’s current NAACP chapter president, said the NAACP gets about 10 complaints per year about law enforcement across Southern New Hampshire. As he puts it, “law enforcement exists within the context of the larger society.”

Lett said that larger society, because of its history, arbitrarily attributes characteristics to people of African descent “that are fairly negative: criminality, violence, that kind of stuff – so the police approaches them differently.”

Disparities increase during bail setting

The police, however, are just the beginning.

State law requires judges to release defendants on personal recognizance unless the judge or bail commissioner “reasonably” concludes that person is a threat or a flight risk. While blacks and Hispanics make up eight percent of the Hillsborough County population, they make up 16 percent of county arrests, and 27 percent of those who are locked up while awaiting trial.

Population numbers for those incarcerated in Hillsborough on charges other than drug, theft, and assault offenses are relatively small. Still, the common charges for which people of color are most over-represented while awaiting trial are criminal threatening, assault, and resisting arrest.

Gilles Bissonette, legal director at New Hampshire’s ACLU, said it’s not surprising the state’s numbers are similar to national trends. He cited decade-old research from The Sentencing Project, which ranked New Hampshire as having the 19th highest rate of incarceration among blacks, and the sixth highest rate among Hispanics. He called such disparities “very concerning,” and said, “It needs to be looked at in great detail by criminal justice leaders and politicians.”

“Being subjected to pretrial detention, particularly if the individual is low-income and committed a nonviolent offense, like a drug offense, it can cause job losses, evictions; it could cause issues with custody of children,” Bissonette said.

Because New Hampshire’s non-white population is increasing, Bissonnette said, the ACLU will be committing more resources to racial justice issues.

Administrative Judge Ed Kelly oversees the state’s circuit courts, where his job includes assuring consistency in the courts, while protecting judges’ discretion. Kelly said unlike some other states, New Hampshire doesn’t have a computer program designed to predict defendants’ risk levels and standardize bail practices, known as a “risk assessment tool.” Kelly said he tells the state’s 47 full and part-time Circuit Court judges to “strip away every conceivable bias that they may have,” whether it’s about people with addictions, poor people, or something else.

It’s been years, however, since judges have had any training on the matter. Kelly said that now that the issue is in the news – and because New Hampshire has many new judges -- he hopes to have more bias-training for judges.

Efforts underway

There are efforts in New Hampshire to reduce inequities in the justice system.

- In addition to requiring more bias-training for judges, Kelly is considering bringing computer-based risk-assessment tools into practice. These are not a panacea, however. ProPublica has shown these tools can also be biased against blacks.

- New Hampshire does have a coordinator and committee dedicated to reducing contact between juveniles of color and the criminal justice system. Andrew Smith has spent the last five years working to reduce arrests and encourage diversion among justice-involved youth across the state. Over the last few years, he's had some unusual, quantifiable success reducing contact between kids of color and the justice system in Hillsborough County.

- In Nashua, police have had a particularly negative reputation among minorities in years past, according to NAACP officials. After a new chief was appointed in early 2015, however, officers and a committee of residents began meeting monthly to build trust.

Read our methodology to see how we crunched the numbers.