Stunning images this week out of the Big Island of Hawaii show lava flows from the Kilauea volcano inching closer to the village of Pahoa.

As of Saturday, the lava's leading edge is stalled just a few hundred feet from the nearest home and the main road.

But John Lockwood, a volcanologist who lives near Pahoa, says underneath the flow, there's activity in lava tubes, or what he calls pyroducts.

"Right now, even though no lava is being supplied directly to the flow-front, there's plenty of what we call breakouts. Lava is breaking off from the sides of the flow further upslope and sending out new flows," he says.

It moves so slowly that one might wonder if there's anything humans can do to stop or divert the flow.

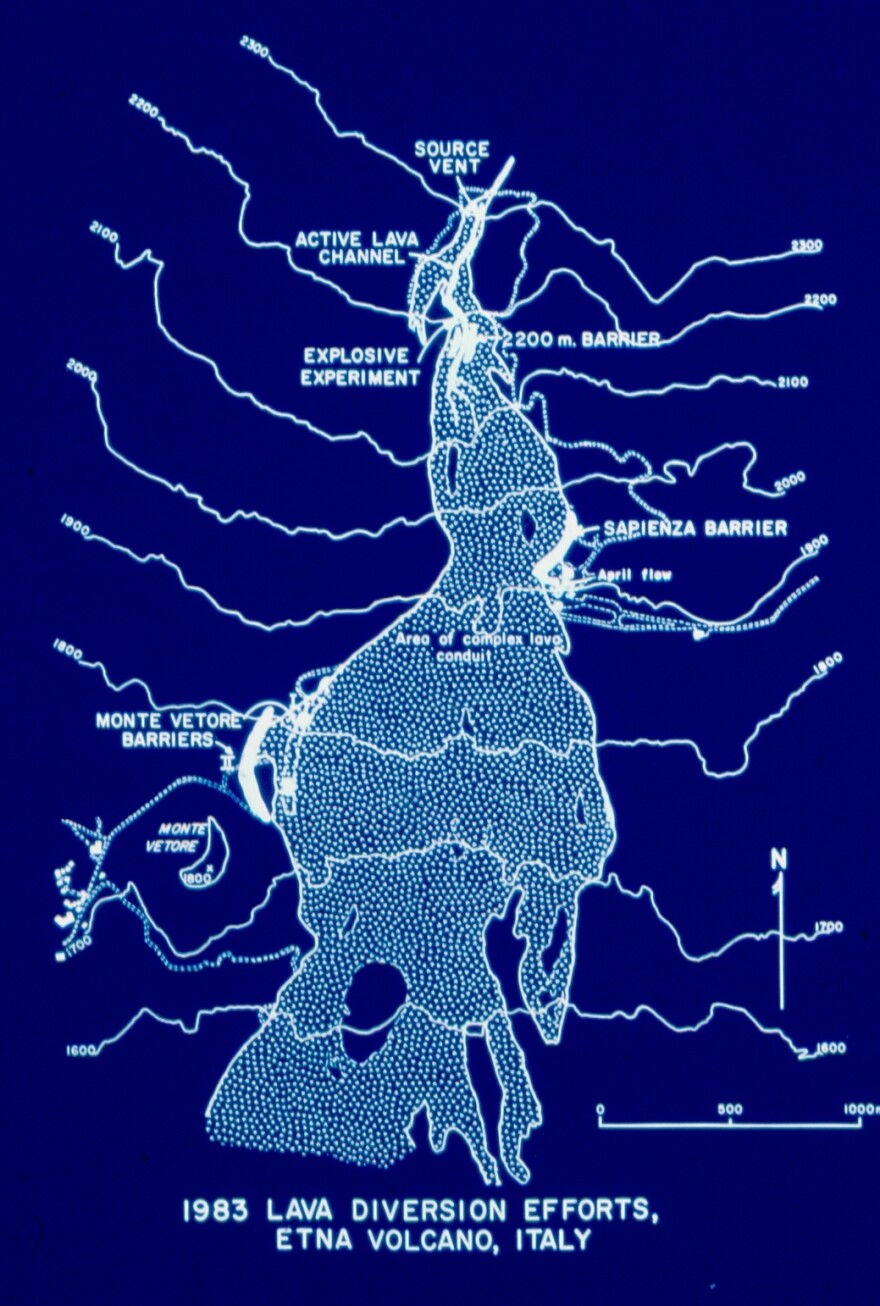

In fact, lava diversion is possible. Lockwood knows all about it: He was an American adviser during the 1983 volcanic eruption of Mount Etna on the east coast of Sicily.

"Mount Etna is a complex volcano," he says. "It looms above the major city of Catania on the island of Sicily. Etna is one of the world's most active volcanoes."

To save the towns below, teams scrambled to divert the lava.

"It was a massive engineering effort involving several hundred men and hundreds of pieces of equipment," Lockwood says.

Workers were on the front lines. They gouged out channels in the lava, then inserted and set off explosives; they also used bulldozers to build giant earthen walls to divert the flow.

"In some cases, a bulldozer is actually driven over red, incandescent lava to be able to push it up," Lockwood says. "Five minutes on the flow and then the bulldozers have to be pulled away. The fire department would spray massive amounts of water to cool down the bulldozers. It was pretty heroic efforts."

While the project cost an estimated $2 million, Lockwood says they saved about $100 million worth of property from destruction — all with bulldozers and explosives.

There is another technique, but it only works near the ocean: Dump massive amounts of sea water to chill and solidify the molten rock. That worked once in Iceland back in 1973.

No matter how you do it, diverting lava is complicated.

"First of all, the terrain has to be amenable," Lockwood says. "The economics have to be right. What will be the cost of diverting the lava flow? What are the benefits that you hope to achieve if you're successful? There's always that element of 'if.' "

Some efforts in the past have failed — including in Hawaii.

"Lava diversion has been attempted in Hawaii in 1955 and 1960," he says. "And they were futile; they were not well-engineered, people didn't know what they were doing, and they failed. Barriers were destroyed and towns were overrun."

Plus, politically, it's a risky decision. Lava diverted from one town could flow right into another.

And even some residents in Pahoa, whose homes are in danger, don't want to divert the lava. As of right now, there's no plan to do so.

"Our volcano has deeply held religious significance to lots of people, to the Hawaiian people," Lockwood says. "Heck, to non-Hawaiian people that have lived here a long time. You know, I've been in Hawaii for 40 years, and one ends up with a great deal of respect for the volcano. 'She' — we refer to our volcano as 'she,' because we're talking about Pele, the volcano goddess — she deserves respect."

At a public meeting held in September by Hawaii County Civil Defense and the U.S. Geological Survey, Pahoa residents spoke out against diversion.

"You cannot change the direction. It's Mother Nature. It's like me telling you, 'Move the moon because it's too bright,' " one woman said.

Still, if the lava flows pick back up near Pahoa and continue in the same path, diversion might be a consideration.

"There's some very large subdivisions with over 1,000 homes that could be in jeopardy," Lockwood says.

But any sort of diversion would be a temporary fix.

"Whatever the efforts of humans are, they'll be pretty puny compared to the long-term plans of the volcano," Lockwood says.

Especially for Kilauea, which has been erupting on Hawaii's Big Island for over 30 years.

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.