Early-learning programs have always been a tough sell in New Hampshire. Child advocates and educators have tried for years to break lawmakers’ resistance to the idea, yet a proposal to put more 5-year-olds in all-day kindergarten can still roil Concord for months.

A Washington, D.C. political group with deep pockets, a team of lobbyists and a small army of volunteers wants to change that.

Save the Children Action Network, or SCAN, established a New Hampshire operation in 2015, setting up shop in the offices of a prominent Concord lobbying firm. Since then, the group has spent well over a half-million dollars on an agenda that includes an experimental model to finance preschool programs for 4 year olds.

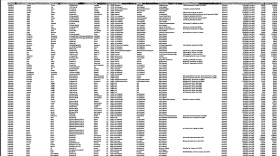

SCAN’s investments include:

- Nearly $431,000 for mailers, digital ads and polling to support two candidates for governor, including Democratic nominee Colin Van Ostern;

- Financial sponsorship of a series of televised forums for presidential hopefuls; SCAN also bought $140,000 worth of digital and TV ads;

- $88,000 for a campaign to back 21 Manchester aldermanic and school board candidates who pledged to increase investment in pre-K education;

- $13,000 for lobbyists to push a bill in the State House, drafted with SCAN’s help, that would solicit private investment in early-childhood programs.

The organization's investment in New Hampshire is significant, especially in this year's governor's race, where SCAN's spending on the primary far exceeded that of any other outside group.

“We want to be the political voice for kids,” said Brendan Daly, SCAN’s senior communications director. “We want to be out there talking about early-ed and trying to get the candidates, whether at the presidential level or the state level or the local level, talking about it because we feel it’s an important issue that doesn’t get discussed enough.”

Daly acknowledged that building political support for early-childhood education in New Hampshire is a work in progress. But SCAN appears in it for the long haul, and the group’s strategy, from paid media to grassroots organizing to statehouse lobbying, is a window into how special interests try to steer the debate on public policy in New Hampshire.

Bipartisan politics

SCAN is the political arm of the Save the Children Federation, an international child-welfare organization with a dual mission: preventing maternal and newborn deaths; and getting more U.S. kids into preschool programs.

The group has received at least $13 million from the Save the Children Federation since it was founded in 2014. Whether SCAN receives funding from other sources is hard to know: as a tax-exempt 501(c)4, it is not required to disclose its donors.

But the group has been generous with candidates and causes aligned with its mission. In the run-up to New Hampshire's September 13 gubernatorial primary, SCAN accounted for four of every five dollars of the nearly $500,000 in outside spending on the two races.

Unlike many political groups, SCAN has taken a bipartisan approach in its spending. In addition to endorsing Van Ostern, the group spent about $200,000 to support Jeanie Forrester’s unsuccessful bid for the Republican nomination. (Forrester and Jonathan Lavoie were the only Republican gubernatorial candidates to answer SCAN’s candidate questionnaire, Daly said; all the Democrats in the field responded.)

The group’s work in Manchester before the city's 2015 elections was similarly bipartisan. And it may have been the difference in several races that were decided by fewer than 100 votes.

SCAN’s "Don't Wait. Educate" campaign touched every ward in the city. Volunteers made 8,000 phone calls, visited 3,000 households and mailed out 150,000 postcards, according to the group. It also sponsored radio and newspaper ads.

Of the 21 candidates who signed SCAN’s “statement of principles,” pledging to expand early-childhood education in Manchester, 13 won -- including at least two Republicans.

Meryl Levin, who founded New Hampshire’s first public Montessori charter school, was co-chair of the “Don’t Wait. Educate” campaign. She said SCAN’s investment paid off. It put data on early education in the hands of candidates and voters, and it laid the groundwork for policy changes in Manchester, a city where more than half the school-age children receive free or reduced-price lunch.

“There are people in New Hampshire who have been working on early-childhood education for a long time, but I don’t think they were engaged in media or worked beyond those circles in quite the same way,” Levin said. “Part of that is because Save the Children [Action Network] had the resources to do that, and that was their goal very clearly. I think it had a real impact.”

A new model

While there may be nothing less politically divisive than the welfare of children, how to pay for it is another matter. On the state level, SCAN is trying to transcend that battle by bringing private investors to the table.

It’s called social-impact bonding, or “pay for success.” The start-up costs are funded by banks, charities and other private entities. If the program meets its goals and saves public money, the state pays back the investors with interest. If not, the investors -- not taxpayers -- are on the hook.

In 2015, SCAN helped draft a bill, sponsored by Democratic Sen. David Watters of Dover, that would set up a commission to study the pay for success model. The bill cleared the state Senate, but failed in the House.

Undeterred, SCAN hired the Institute for Child Success, a South Carolina research and policy organization that advises policymakers and government agencies on the pay for success model. Meanwhile, Watters and lobbyists from SCAN met with other lawmakers, child advocates, state health and education officials, and charitable organizations.

The bill they came up with this year, SB 503, went even further than the first one. It proposed authorizing the state to award pay-for-success contracts for pre-K programs for 4 year olds. It would create an 18-member commission to review requests for proposal and appoint an “independent evaluator” to determine whether the program met its goals of improving third-grade reading scores and reducing special education enrollments.

“We decided that, with pay for success, you really have to have something measurable, that saves money, so that you can justify spending the money,” Watters said.

The bill initially would have allowed the state to issue up to $10 million in bonds to pay back investors. That provision was later removed. But after passing the Senate, the bill was once again defeated in the House.

Watters said questions about how much, if any, state money should go toward education played a role in SB 503’s failure. So did the belief among some lawmakers that the state should focus on funding all-day kindergarten.

Then there was the concept itself, which is relatively new and untested.

“It really does take some explaining for people to figure out how it works,” Watters said.

Indeed, less than a handful of pay for success programs have existed long enough to properly evaluate, and the results have been mixed.

In 2012, teenage inmates at New York’s Rikers Island prison received group therapy to reduce the chances they would re-offend after their release. Three years in, a report found it had no effect on the recidivism rate. The program was shut down, costing Goldman Sachs, which put up the money, $9.6 million.

Two early-education programs financed by pay for success may or may not prove more successful in the long run.

In May, the first of four annual evaluations of the Chicago Child-Parent Center found that 59 percent of the first cohort of preschoolers were considered ready for kindergarten. That triggered $500,000 in “success payments” for investors who put up $19 million for the program, which targets 4 year olds in high-poverty neighborhoods.

The state of Utah paid investors $267,000 after only one of 110 “at-risk” 4 year olds in a school-readiness program needed special education after kindergarten. The 99 percent success rate was challenged, however, by skeptics who told the New York Times it was too good to be true. One expert said the program either “performed a miracle, or these kids weren’t in line for special education in the first place.”

Trying again

Watters said he plans to introduce a modified version of SB 503 in January that would allow Manchester and other municipalities to use the pay-for-success model.

Despite the past resistance in the State House, Watters is optimistic. The state's business and philanthropic communities are ready to invest in early education, he said, and there is emerging consensus that it’s not only good for families, but for New Hampshire's economy.

“I think, around the state, a lot of the stakeholders realize it would be good to try and do this,” he said. “We have 14 percent of our children in individualized learning programs now, and that number is growing. Financially, it’s putting so much pressure on school budgets.”

Even if the bill passes both chambers, it could be several years before a privately financed pre-K program is launched in New Hampshire - and even longer before anyone knows if it works.

Watters said all-day kindergarten is his first priority in the next biennial budget, so funding for pre-K won’t likely be available until 2019. Once a program is up and running, evaluating the third-grade reading skills of the first cohort of 4 year olds would take another four to five years.

Daly said SCAN is prepared to keep working in New Hampshire. The group’s local “mobilization manager” recently met with child advocates, supportive lawmakers and state officials to talk about how to get the bill through the House, and the group is involved in developing a proposal for a model preschool program in Manchester.

SCAN has also continued its support for Van Ostern’s campaign for governor. The group recently spent another $32,000 for polling on the issue, and Daly said there are plans for direct mail and digital ads later this fall.

“Early education is important to us,” he said. “That’s why we’re doing this.”