The energy grid is vastly more complicated than it was ten years ago. The old model was to plug in and pay for what you use, but now the grid is starting to ask for something back from consumers. This change is aimed at flatten the demand curve.

Think about how you use electricity: you wake up, turn on some lights, and maybe have a hot shower. After work you come home, cook some dinner, and watch TV. In the winter, maybe you heat with some kind of electric heat, or – even more likely – maybe in the summer you switch on AC.

At the same time, millions of others are doing the same thing and that sets up big peaks and valleys in electricity demand. New England has two seasonal peaks: one in the dog days of summer, and another smaller one on the coldest winter days. These peaks are a problem, which we’ll get back to.

Flattening the Curve

Gordon Van Welie, CEO and President of the Grid’s operator, ISO New England, says one way of dealing with this is not just to put power plants on the grid, but to reward big electric consumers – factories and such – for getting off.

“Really that’s what’s driven us from hundreds of assets to thousands of assets that we’re having to keep track of,” Van Welie explains.

The ISO says those thousands of assets represent 1,100 megawatts worth of demand that can be shaved off the peaks: that’s just shy of five percent of New England’s record peak demand. This usually works by factories switching on big diesel generators at peak hours so that they can unplug from the grid.

But Mike Hogan – who works for the Regulatory Assistance Project advising policy makers on how to get carbon out of the electric supply – says now folks are getting more creative.

For example, say the manager of a big office building wants to run the AC all day, but doesn’t want to pay daytime electricity rates. Hogan says “It’s relatively straightforward to install a system. In this case if it’s for air conditioning you would make ice and store the ice, and delivered chilled air at the time that he wants it.”

Another Use for Storage?

So, low off-peak prices can be stored for use during peak hours in a lot of ways. That brings us to Seabrook New Hampshire, where Richard Brody, a Vicepresident at SustainX shows off a prototype air compression electricity storage system.

“Taking power from the grid, compressing air, storing that air, and then reversing that process to run the air through our machine and generate power again,” is what it’s all about.

SustainX was founded on the invention of a couple of Dartmouth graduates. Their huge, super-efficient air compressor is special because it’s isothermal. That means that they’ve come up with a way of keeping it from giving off too much waste heat.

And while it’s a new technology Brody says it’s built on the back of a tried and true invention: a diesel ship’s engine. “These type of engines, this family of engines, powers 80 percent of the world’s marine fleet,” he says, signaling a once naval-green hulk of metal that has been re-painted SustainX blue, “Very dependable, very mature technology.”

The technology was imagined as a way to smooth out the supply provided by intermittent renewables like wind, but its developers say any factory could use it to provide power on demand.

The test facility SustainX is building will be able to put away 2 megawatts of air. It’s small, but it’s still “grid-scale”: about enough to power 1,000 homes.

Technologies like this can, in turn, make power cheaper overall. That’s because there is literally a fleet of power plants that just sit for most of the year, waiting for those peak hours and seasons. The problem of having to fire up these expensive and often dirty power plants is what the grid operators are trying to solve.

Residential Solutions

The solutions aren’t limited to factories and huge electricity consumers. For example, some utilities will give electric hot water heaters to their residential customers for free in exchange for letting the utility control the heater. The power company can turn off heaters during peak hours. Folks can still use the hot water stored in the tank, but the heat gets stored back up when electricity is cheap.

These types of technologies are part of what those talking about Smart Grids are referring to. In New Hampshire, the New Hampshire Electric Coop is the only utility making these improvements in a big way on the residential side, helped by a $17 million dollar stimulus grant.

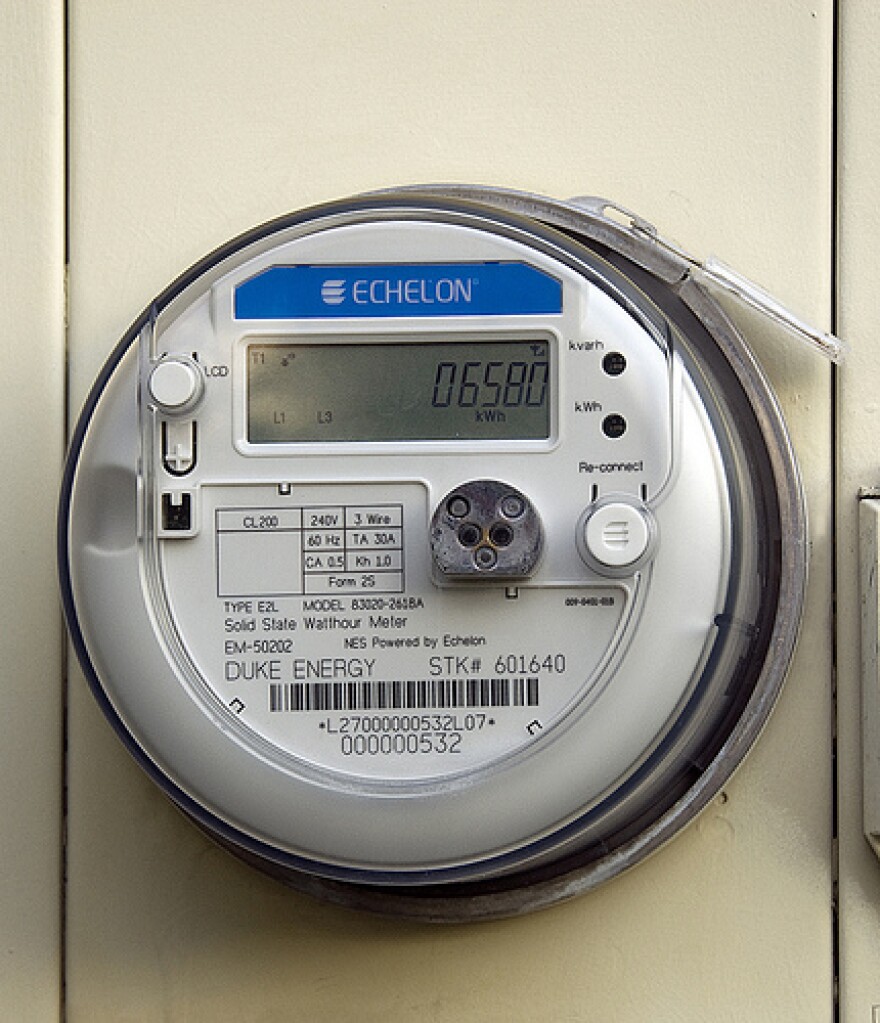

The Coop serves about 38,000 meters in the central part of the state and Communications Director Seth Wheeler says, “We just recently finished installing our new Smart meters in all of those locations.”

It’s working with a few hundred customers to pilot something called a dynamic pricing model. This charges more for consumption during peak hours and less for off-peak, giving an incentive to conserve during the peaks.

It can save utilities money too since the meters report usage automatically. “We cover nine out of the ten counties and we’ve got over 5,500 miles of line,” says Wheeler, “So meter reading costs alone, there are significant savings to be realized there.”

But also, the utilities pay into a regional pool that is used for necessary upgrades to transmission lines, and the rate they pay is based on their peak demand and smoothing that peak reduces those payments as well.

This type of program would take millions of enrollees to make a difference on a grid scale, and so far in New Hampshire it’s not widespread. But if these changes pick up steam across the region, it could facilitate another big change that has been talked about for decades now: turning each individual home into a power-house.

That’s next time; can distributed generation really ever take hold?