Rain clouds are just starting to roll in over Franconia and Chris Brooks is leading me through saplings and overgrown grass. We’re trying to find a trace of the buildings that once stood here.

“It’s always hallucinogenic when I come in here, because it doesn’t look like anything I remember,” Brooks says.

Brooks spent about eight years of his life at this spot, first as a student and later as a teacher at what was then known as Franconia College. The school attracted about 400 students at its height.

Brooks is trying to find the spot where one of the College’s main buildings once was. It was the backdrop for a group photo from decades ago. But we never find it.

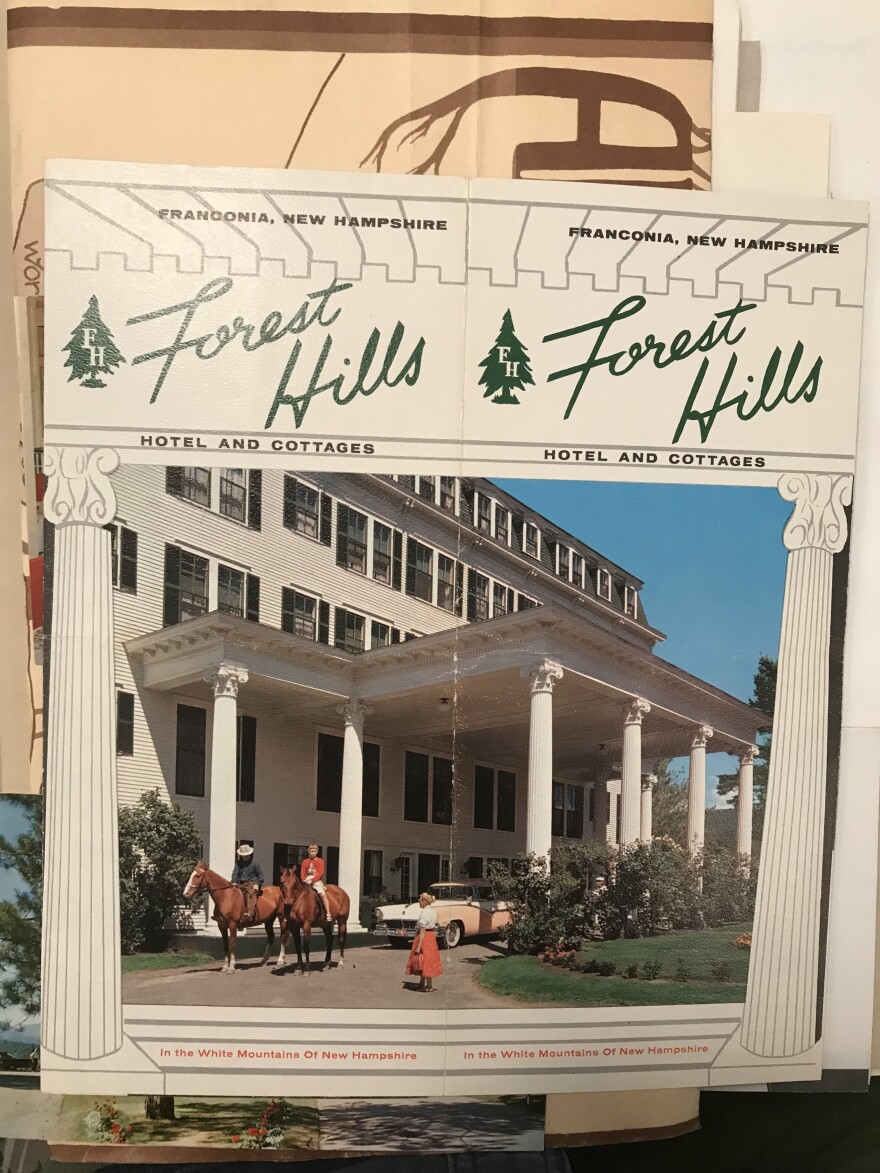

The story goes, the town of Franconia wanted to do something with a decaying old hotel called the Forest Hills. Once a resort that drew tourists to the area, the Forest Hills was starting to become more of a blight for Franconia. So town leaders decided to turn it into a college.

Students helped fix up the place and attended class in rooms filled with leftover hotel furniture. Franconia College was very different from other institutions of the time.

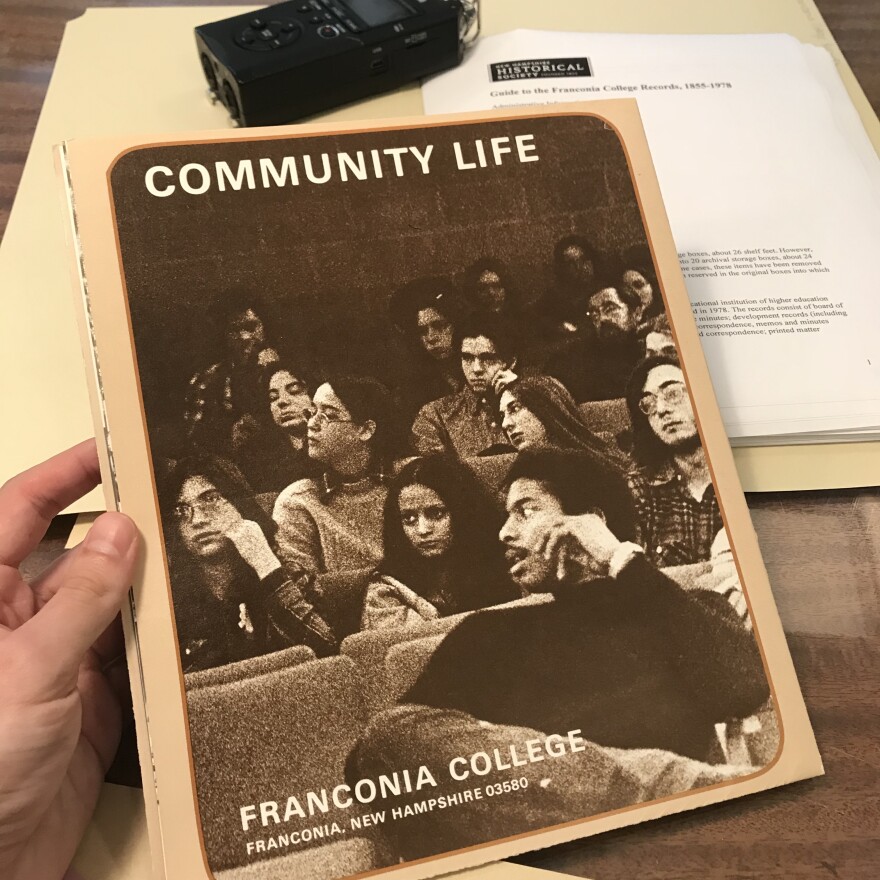

There were co-ed dormitories, organic farmers, flexible courses and a ‘if you want it, build it’ mentality.

“It was hippie-ville,” Brooks says. “We disdained all forms of formality and conventionality.”

Students had representation in educational policy decisions, they built their own dormitories and radio stations. But most of that is long gone now. There isn’t even a marker to let passersby know what was here.

“This was a beacon for everything that was happening in the 60s,” Brooks says.

“The history vanished and we became, simply, for a few years, Franconia College. Not really bound by time or space, just its own unusual entity.”

Keith Talbot was a student at Franconia College in the 1960s.

“Just like the music from that era, I think Franconia was an optimistic response to a very threatening time,” Talbot says.

Talbot went on to https://vimeo.com/237817211" style="background-color: transparent; font-family: Arial; font-size: 11pt; white-space: pre-wrap;">work at NPR, where he pioneered a new kind of radio. He says that work was inspired, in some ways, by the intersectional education he got at Franconia.

“Franconia was like, ‘wow’ an entirely new interpretation of the world. And it seemed like that was sorely needed at that point. With the war raging, with the future certainly for anybody, any boy who was 18-25 years old -- and therefore subject to the draft -- at the very least I think we were all seeking an explanation of why our lives were being put into jeopardy... And most of us were there to get away from that world, to examine that world. Maybe even to create a better world,” says Talbot.

With music and arts festivals, some of the new ideas on campus spilled out into the community. There were educational exchanges with a nearby prison and a daycare center where students could study early childhood education.

Judy Fleischer had herdaughter inthat daycare while she attended Franconia College.

“I was a single mother, so I wasn’t a typical student up there in that I didn’t live in the dorms. I didn’t hang out a lot with the students. I worked, I went to school and I was being a mother,” says Fleischer.

With the help she got with child care, she could take classes, work full-time and do a little bit of teaching at Franconia.

“You know, I don’t know where else I could have -- in exchange for teaching a couple of classes -- gotten an education,” Fleischer says.

Artist Peter Bradley taught painting at Franconia college in the early-70s.

“There’s nothing really like that school I think anywhere, Franconia,” Bradley says.

Bradley is also known for his work as an art dealer in New York City and for organizing what’s considered one of America’s first racially-integrated art exhibitions.

As one of thee few African American faculty members there, he says some in the town were surprised to see him.

“There’s a woman at the bank -- which was very peculiar. I would go to the bank and she’d just hand me money. Well, how much do you need, Peter? And I said, ‘what’s going on here?’ I just felt she was being nice because she didn’t know anybody black. She told me ‘I’ve never met a black person in my life, ever.’” Bradley says.

Former students and faculty say Franconia was a special place. The seclusion, the dark nights and the freedom were a welcome respite to the turmoil of the time. With the battle for civil rights in America, race tensions, and the Vietnam War, students felt they could regain control of their lives, at least for a little while, at Franconia.

By the late 60s though, people outside the boundaries of campus began to voice concerns about how students and faculty were affecting the area.

Former student Keith Talbot recorded part of a community meeting from 1968. In the scratchy audio, you can hear the college president at the time describe a conversation with 10 members of the Franconia Chamber of Commerce who were signaling they wanted the college to close.

“We were asked some questions,” temporary college president Larry Lemmel says on the tape. “The questions had to do with bare feet, students who smell bad because they don’t bathe often enough, long hair... and certainly the whole aura of moral degradation was strong.”

Talbot and other students had come to Franconia to escape the turmoil of the time, but they couldn’t keep the world at bay for ever.

Back at the site of the college, Chris Brooks remembers what he sees as the beginning of the end for the school.

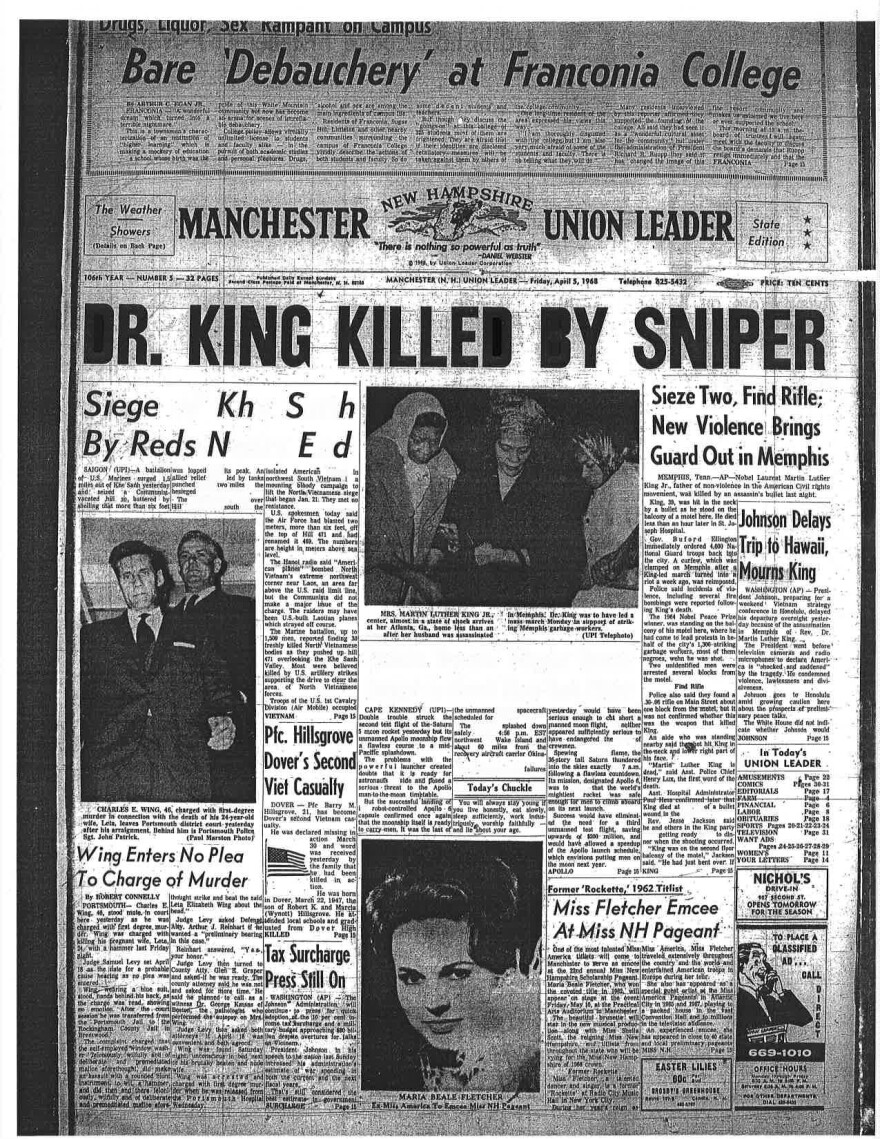

“The Union Leader got a disaffected faculty member here, who called ‘em up and said ‘There’s communism going on here,’ Brooks says.

Around that time state police conducted a raid on the school. And then the Union Leader ran a story.

“And it’s a famous headline, you can see it online: “Bare Debauchery at Franconia College.”

But below the Franconia news, there was another headline. This one having to do with the national news of April 5, 1968.

“It was Martin Luther King’s assassination,” Brooks says. “It was on the same front page.”

The college continued on. But the negative press was ongoing. There was more pushback from local officials and financial trouble. Franconia eventually closed its doors in 1978.

“Now it’s passed on to the realm of the mythological,” Brooks says.

There is a Facebook group though, where Brooks keeps up with fellow alumni and faculty.

Most physical remnants have long since rotted away. But Brooks never left Franconia and others didn’t either.

Former students would go on to become state senators, open local bookshops and found companies that still exist in the Franconia area.

Brooks says Franconia College gave a sleepy town with a past, a future.