Off the coast of New Hampshire are the iconic Isles of Shoals.

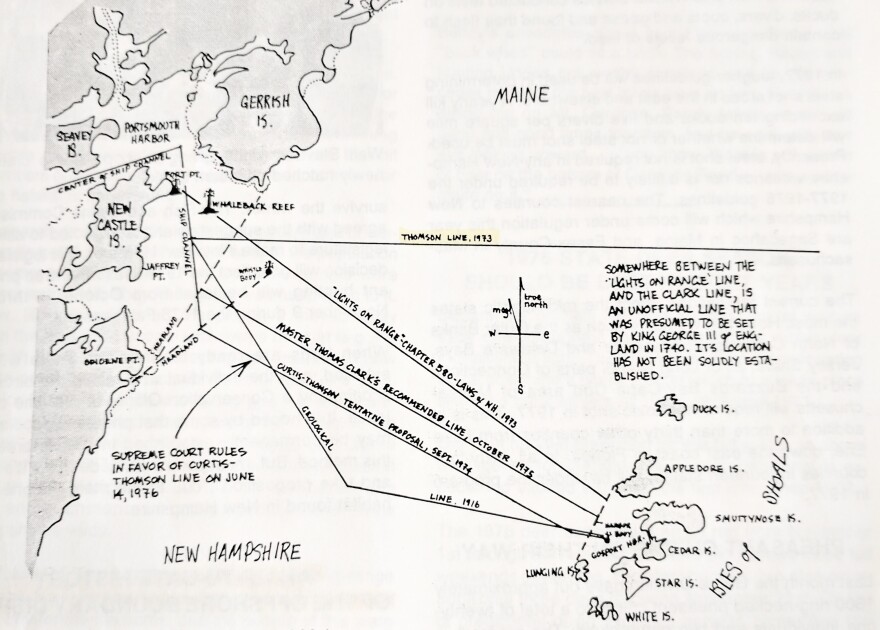

Somewhere around the middle of those isles is a dotted line -- the state border between New Hampshire and Maine.

As part of our series Surrounded in which we look at life in and around New Hampshire's islands, Jason Moon found out that line has been the cause of some intense disagreement over the years.

I’m standing on the island of Newcastle right now, looking out at where the Piscataqua River meets the Atlantic Ocean.

Across the river in front of me I can see the state of Maine, and if I look way out to sea I can just make out the Isles of Shoals.

Now, between me and Maine I can also see two lighthouses. One of them is on the island here with me; the other is a bit further out to sea.

“That’s the line we’d use. We probably used it a century or so, between the New Hampshire and fishermen.”

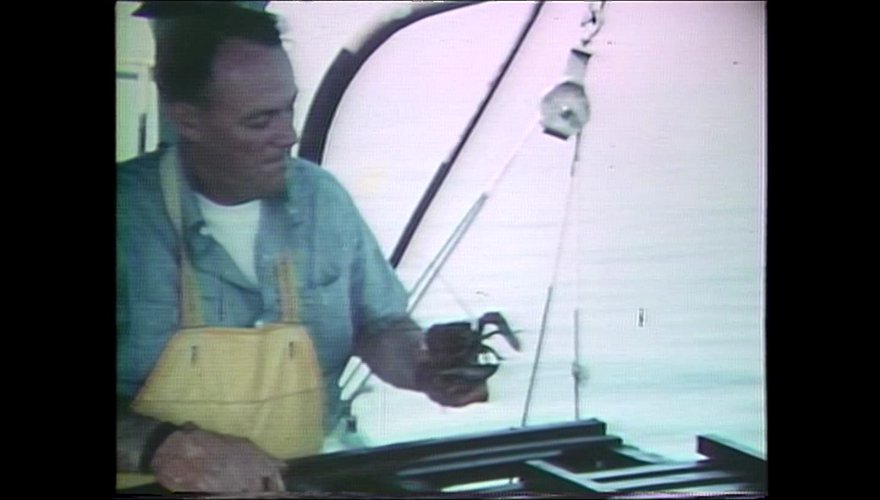

That’s Jack Newick, a lifelong lobsterman from Dover.

Newick says in the old days, if you were out at sea, all you had to do was imagine a straight line connecting the lighthouses– and that was the border. They called it the “lights on range."

“To think, that in the early 70s, certain borders hadn’t been established yet.”

That’s Roland Goodbody, an archivist at the Portsmouth Athenaeum.

He says the “lights on range” had no legal basis, it was more of a gentleman’s agreement.

That agreement fell apart in the 1970s with what became known as the lobster war.

“Seems to me it could’ve been avoided entirely by Maine and New Hampshire agreeing on the same size lobster that you could catch.”

In the late 60s, concerns about overfishing had led both states to enact minimum size restrictions on lobstering. But their minimum sizes were different, by one 16th of an inch. So suddenly it mattered to state officials where lobstermen set their traps.

Newick, the New Hampshire lobsterman, remembers how it started.

“For some reason, one particular Maine fisherman, he was a mean, ornery son-of-a-gun and he called the state of Maine down to establish a line.”

Maine game wardens responding to the call found a New Hampshire lobsterman named Ed Heaphy with lobsters in his boat that were illegal in Maine. But Heaphy, using the “lights on range” said he wasn’t in Maine, he was in New Hampshire.

The wardens disagreed. Things escalated. Ed Heaphy’s shipmate, Brockie, had a loaded pistol.

“The wardens tried to board the boat. Eddie said, 'you’re not going to take my boat away from me.' And Brockie is going, ‘Ok Ed you take care of those two, I’ve got these two right in my sights right now, no problem.’”

Ultimately no shots were fired that day, and Heaphy went with the wardens.

But when word of this standoff reached then New Hampshire Governor Meldrim Thomson, the real action began. In 1973, Thomson had just taken office.

Candus Thomson, no relation, covered Mel Thomson for several state newspapers in the 1970s.

“He was kind of a badass in a really nice suit, you know?”

Here’s a quick highlight reel:

He lobbied for the New Hampshire National Guard to have nuclear weapons.

He the replaced the word “Scenic” on the state license plate with “Live Free or Die.”

When a man with religious objections covered the phrase on his license plate, Governor Thomson put him in jail.

“Mel like a good fight. I mean, it was like, ‘he didn’t…he did! You know, he did!’”

When this battle over state sovereignty broke out, Governor Thomson was quick to jump in.

“Any dispute like this just kind of triggered this inner compulsion of his.”

Tom Rath was an attorney in the Department of Justice under Thomson. He says in the long history of Thomson’s fights, this one stands apart.

“If you take some of the cases, they are probably just to the south of crazy. But this doesn’t fall in that, in my judgment. It was and remains a legitimate question.”

Thomson came out swinging.

He sent his Attorney General to personally defend the New Hampshire lobsterman, Ed Heaphy, against the charges in a Maine court.

In a speech, he called New Hampshire fishermen “soldiers on an important battle line for the state.”

The dispute went to the Supreme Court, which passed it back to the states.

For all the tough talk, the two states did eventually agree. They placed the border where it is today: North of the line claimed by Maine, but South of the “lights on range.”

To New Hampshire fisherman, like Newick, it felt like a betrayal.

“New Hampshire blew it – 1700 acres.”

Some New Hampshire fisherman never stopped fighting.

Harrison Workman, a lobsterman who went by the nickname “Workie”, spent the rest of life in search of historical evidence to back New Hampshire’s claim to the old line. He even traveled to England and spent 9 days poring over colonial maps in the archives of the British Admiralty.

Workie spoke to New Hampshire Public Television in 1982.

“The boundary means so much to me that I just cannot give it up. And a lot of people in Maine wish I would, I suppose. But I’ll never give it up as long as there is a ray of hope.”

There was new hope in 2000, when another border dispute arose and the states went back to the Supreme Court.

This time the argument was over the ownership of the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard.

New Hampshire lawyers used Workie’s maps and research to prepare their arguments.

The court issued its ruling in 2001.

Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, speaking for the court, said because of the way the two states settled the lobster war, New Hampshire couldn’t make a claim on the shipyard.

“Twenty-four years ago, in a lobster fishing dispute between the two states this Court entered a consent judgement fixing the Maine – New Hampshire boundary."

Thus, the state boundary was fixed.

Except it might not be, at least not entirely.

Lobstermen will tell you there’s good fishing on the far side of the Isles of Shoals. But after contacting half a dozen government agencies and consulting state statutes, the maps just aren’t clear on where Maine waters end and New Hampshire’s begin out there.

Which raises the possibility of yet another border dispute between the states.

“I guess we’ve learned to live with that," Tom Rath says.

“There are some things the mind of man is not meant to know, and that line may be one of them.”

One difference now: both states use the same minimum lobster size of 3 ¼ inches.