The classic gerrymandered map you learned about in high school civics class is full of oddly-shaped legislative districts, drawn with obvious intent to boost one party.

But in New Hampshire, that’s rarely the case: It’s very hard to see, just by looking at the election maps, which districts might help or hurt a certain party’s chances.

So has gerrymandering been a factor in the state’s politics? And if so, how much?

New Hampshire Public Radio crunched 30 years of election data, focusing on the state Senate. And that analysis revealed an undeniable gerrymander that, with few exceptions, benefits Republicans.

Related story: How a Few Lines on a Map Hold So Much Power in N.H. Politics

In the majority of those three decades of elections, Republicans have enjoyed a disproportionate advantage in the allocation of seats. As New Hampshire has turned into more of a swing state over the past two decades, the state Senate, with just a handful of exceptions, has remained in Republican hands. That’s because Republicans have been the ones drawing the political map for decades.

We’re focusing our analysis on the state Senate because with just 24 districts, it’s a much clearer field to work with than the 400-member New Hampshire House, where most districts elect multiple members and some towns are in overlapping districts.

Until recently, there hasn’t been a great formula for how to measure partisan gerrymandering. Racial disenfranchisement or visibly absurd lines cutting through neighborhoods are typical benchmarks when gerrymandered maps have gone to court. But to uncover what’s going on in New Hampshire’s map, we’re using a new framework for measuring the gerrymander, being tested in a handful of court cases nationally, called “The Efficiency Gap.” (Here’s a more in-depth explanation of the concept.)

The metric hinges on what researchers call “wasted votes.” A vote is wasted if it had no impact on the outcome of a given election. So, any vote for a winning candidate that’s in excess of the number needed to win that race is counted as wasted, since the candidate didn't need it to secure victory. And any vote for a losing candidate is also considered wasted, since it had no impact on the result.Some number of wasted votes are inevitable in any contested election. In a truly neutral legislative map, Republicans and Democrats will have roughly the same amount of wasted votes.

But creating districts that minimize wasted votes for one party’s candidates and increase the number of wasted votes for the opposing party—that, in essence, is gerrymandering. The result is an electoral map that reflects partisan intent over voter intent in the final tally of legislative seats.

So, if you count up each party’s wasted votes and divide that figure by the total number of votes cast, that number is the “efficiency gap." It tells you how much of a disproportionate boost a party got in an election. What that number measures: How much larger a share of seats did a party receive, above what it would have gotten from a neutral legislative map?

What does that look like for New Hampshire over the past few decades? In the chart below, positive efficiency gap figures indicate an outcome disproportionately favorable to Republicans; negative numbers show a Democratic advantage. In both cases, the bigger the number, the bigger the advantage.

How Many Votes Are Going to Waste in New Hampshire?*

Note: To account for uncontested races (i.e. those in which one party did not field a candidate) we allocated percentages based on the party vote in that district from the most recent presidential election, as a stand-in for partisan break-down. In other words, in a district where no Democrat appeared on the ballot, and the Republican candidate thus received close to 100 percent of the vote, we gave each party the same vote share as it received in the most recent presidential election. Political scientists who study gerrymandering recommend this approach to account for the potentially distorting impact of uncontested races.

The numbers above tell a pretty clear story: The state Senate maps have largely favored Republicans since the mid-1980s, with a handful of exceptions. In fact, in the 11 state elections since 1994, Republicans have often come out with 10 to 15 percent more seats in the Senate than a neutral map would have yielded. The imbalance has been particularly stark over the past three elections.

The two most recent exceptions to this trend are 2006, when there was no measurable efficiency gap, and 2008, when the efficiency gap actually favored Democrats. Of course, the 2008 election saw New Hampshire Democrats buoyed by the national pro-Democratic wave from President Obama's first-term victory. This seems to indicate that the gerrymandered aspects of the Senate map aren't strong enough to withstand overwhelming wave elections for Democrats. But in more typical election years, such as 2012 and 2014, Republicans clearly enjoy a leg up when it comes to allocating New Hampshire's Senate seats.

In most of the years we examined, Republicans would have come away with the Senate majority even without the benefit of the efficiency gap. But it enabled them to pad their majorities in most years, and in at least one year (2012) provided them with a majority of Senate seats despite coming up short in the popular vote.

At the same time, New Hampshire’s Senate districts are growing more partisan: A greater share of districts now lean strongly Republican or strongly Democratic, with fewer so-called “swing districts,” in which either party has a genuine shot at winning.

Gerrymandering Is Pushing N.H. Senate Districts to the Political Edges

Let's focus just on the presidential election results, broken down district by district, and then compare those figures to the statewide results:

Republican presidential candidates have won between 45 percent and 48 percent of the statewide vote in the four elections since 2000. Back in 2000, no individual Senate district varied more than 10 percent from that year's statewide figure (48 percent), with all districts ranging between 38 percent to 55 percent Republican support. By 2012, the range of Republican support across the Senate districts had widened significantly, spanning from 31 percent of the vote to 58 percent – the widest partisan spread in more than two decades.

This means the majority of Senate districts today don't come close to reflecting the statewide Republican/Democratic split. Instead, the districts tend towards either end of the partisan divide.Why is that significant? This isn't simply a natural demographic trend. This is the result of politicians being able to draw the political maps and deciding how voters are grouped.

When more Senate districts tend to lean strongly in the direction in one party, candidates from the other party have much less of a chance of winning. And voters who live in those districts can be deprived of a truly competitive choice in the voting booth. It also means the winners who emerge from those non-competitive districts have less incentive to work with members of the other party or to support bipartisan legislation.

One of the few remaining "swing" districts in the state Senate is District 12, along the Massachusetts border. Democrats and Republicans have traded wins there over the past four elections, with the margin of victory within single digits each time.

But the district has changed significantly over the past two decades. Six Nashua wards and six suburban towns have bounced in and out of District 12 since 2000, and the district has shifted from a largely urban, bluer district to a redder, more suburban one.

That’s meant big changes in election outcomes from year to year.

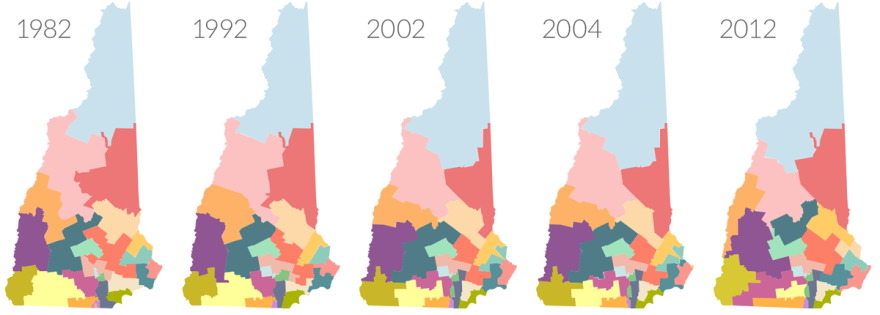

Map: The Shifting Political Lines of District 12

Toggle between election years to see how the shape of District 12 has changed. For a better experience on mobile, turn your device sideways.

In New Hampshire, redistricting is inherently political. Lawmakers draft the maps for the state House and Senate districts, and those maps are approved just like any other piece of legislation. That means the majority party gets to call the shots when it comes to new district boundaries.

Efforts earlier this year to set up independent commissions to handle redistricting went nowhere. The next round of political map-making isn’t for another five years; it seems likely that the current process will stay in effect until then.