In the late '90s, craft beer saw a renaissance of sorts. After years of nondescript light beers almost completely dominating the market, tastes seemed to wake up. Breweries and brew-pubs started up almost overnight. A boom was born.

But with any economic boom, there’s danger of a bubble. Beer is certainly not immune to that. A series of bad misfortunes hit the beer industry. A massive 1997 report contains a number of damning factors, everything from unfavorable demographics to health consciousness. Even anti-drunk driving measures were seen as contributing to the bust.

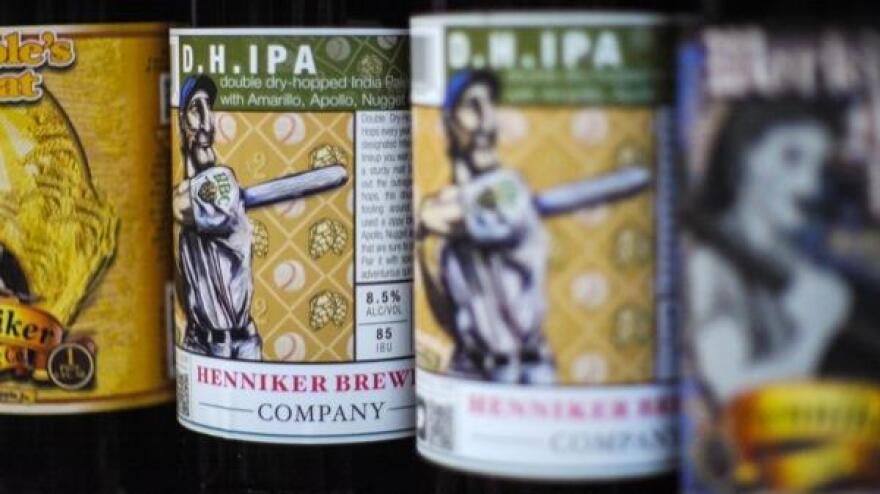

But the biggest and most central factor that led to the eventual demise of most of the sector was product quality and freshness. While many, like Jim Koch of Sam Adams fame, had been pushing for years for “open freshness” dating, the biggest problem was that consumers who made an effort to finally branch out their tastes to craft beer were sometimes met with a sub-par product.

“Today's beer scene was built on the bones of the 90's collapse,” says Bill Herlicka, owner of White Birch Brewing in Hooksett. “In many ways we're in the golden age of brewing. The numbers of brewers open and opening are beyond any historical scale.”

He’s right. Today, there’s another boom brewing in the industry. Craft beer makes up a growing percentage of the overall market, and the United States is now seeing an average of one brewery opening every day.

New Hampshire’s recent nanobrewery licensing is helping to push that number. Today, anyone with $240 and a dream can start their own nanobrewery, a term now quantified by the state as a brewery producing 2,000 or fewer barrels annually. That’s 60,000 gallons or less. While that may seem like a lot, it essentially creates a market for homebrewers wanting to live the dream.

“You're doing everything at the highest cost for the smallest volume. A three barrel system takes as long if not longer to work for one batch as a seven (barrel system) but you’re getting less than half the finished output,” Herlicka says. His brewery, White Birch, came about just before the new laws took effect. In some ways, he started nanobrewing in New Hampshire before nanobrewing was cool. And he’s since increased his output.

So is 2014 any different than 1997? One of the biggest differences between then and now is awareness.

Deep in a wonderfully graphical study from the Demeter Group Investment Bank, called “State of Craft Beer Industry 2013”, a key point is made. Today’s consumer is less concerned with brand than they are with style of beer. Much like the decades-old level of awareness in the wine industry, the average beer consumer now knows the difference between a stout and an IPA. The study points out most consumers, especially Millenials, will seek out a favorite style first, and then find a brand they like.

But as with wine, there’s an undertow of snobbery that few in the industry want to admit. Sometimes craft beer drinkers are their own worst enemy, at least as far as attracting a wider audience for the product they love.

“There's a burgeoning view that craft beer drinkers have become more elitists than ‘wine snobs’,” Herlicka says. “Whether in actual published articles, in casual conversations with friends or groups at beer events. I see real trends of people apologizing for not knowing enough. (This) is not a productive outcome of years of effort by craft breweries.”

Of course, the other major difference between 1997 and 2014 is the the existence of mega-craft breweries, outfits from the original study that are still thriving today. The ones that outlasted the 90's boom and bust, like Sam Adams and Sierra Nevada, are now on the cusp of something else, a new distinction between Bud-Miller-Coors and Craft; breweries that specialize, but have gone national. In the case of Sierra Nevada, the means expanding beyond the very geography that gave them their name.

For newer craft and nano-breweries, New Hampshire is setting itself up for success. Whether the current growth trend means we’re heading for beer’s golden age or another bust, the new licensing laws will likely help cement New Hampshire’s blossoming status as a beer state.

For White Birch’s Bill Herlicka however, the lessons of the 90’s bust shouldn’t be forgotten.

“Some breweries will fail. Some will call it a career and close. ;Some will meander between profitability and loss for a few years and then close. It's the normal course of business.”

“To worry about [a bust] is to worry about the inevitable,” Herlicka says. “I prefer to focus on my own business, my plan for the future and making sure we hit that plan.”

Perhaps, for aspiring New Hampshire brewers, that advice might be well worth drinking in.