With the new Common Core State Standards comes a new standardized test, called the Smarter Balanced Assessment. New Hampshire schools will take it for the first time in the spring of 2015, and in many ways, it’s the new test that will determine how the Common Core is taught.

Students at White Mountain Regional High School will start finals next week, but a few months ago they took the pilot of the new Smarter Balanced. 26 states have signed on to this test, which will replace the NECAP for Math and English. In New England those states include Maine, Vermont and Connecticut. This fall 6,000 schools nationwide took part in the pilot.

Imani Gaetjens-Oleson, Tyler Welch, and Emma Portinari are ninth graders and honor students. In 2015 they will be the oldest New Hampshire students taking the new assessment, which is given in grades 3-8, and grade 11.

Their verdict on the test?

“It was really different, a lot more in depth and difficult,” says Gaetjens-Oleson.

“I remember I had a bunch of questions were it was like replacing exponents. It was just exponents, exponents, after exponents and I was like, ‘uh, I don’t know what I’m doing right now,’” remembers Portinari.

“There’s a lot of multi-part questions that had like 10 questions but each question had 3 parts to it,” explains Welch, “I think there’s a lot of kids who think it’s so hard it’s not even worth trying. That’s what a lot of kids were thinking and they just click random buttons.”

To be fair, the test they took was not what is called “computer adaptive”, and the final version of the test will be. This means that when a student bombs a few questions the test gets easier, until it finds what level a student is at, or it does the opposite if a student is acing all the questions. So, the pilot test was likely a good deal harder.

But even so, students will have a tougher time getting high scores on the Smarter Balanced than on the NECAP.

Their math teacher, John Wood thinks it’s going to take a long time before high schoolers start to do well on the new tests, maybe even more than a decade, “An incoming first grader will have had those common core for what, ten twelve years before they take the test,” says Wood. “I feel that we’re at a level that may be here and the Common Core standards is bumping it up and these kids are going to have to make that leap to what the Common Core is actually testing them on and it’s going to be hard for them.”

“Assessment Drives Instruction”

The Common Core is built on high expectations that start early. The way these expectations build on what comes before is called a “Learning Progression.” Students who haven’t been on that track since the beginning will struggle on the tests.

That’s exactly what has happened in states that have rushed into aligning their tests to the Common Core. In Kentucky, after the first round of tests the number of students scoring a “proficient” plunged by more than thirty percentage points in each grade and subject.

So New Hampshire schools are hurrying anxiously to make sure their instruction matches what’s being tested.

Mahesh Sharma is a Massachusetts based Math education consultant, and former president of Cambridge College. He puts it like this.

“Any assessment drives instruction in this country,” he explained in a recent interview.

In other words, teaching to the test happens, and will continue to happen with the Smarter Balanced. But Sharma believes because these new tests are more demanding, that’s a good thing.

“They are going to ask three years from now explain your reasoning, explain how did you arrive at the answer?” Sharma says by way of explanation. “Unless you start doing that in Kindergarten every day, consistently, you’re not going to prepare them for high stakes tests.”

The Smarter Balanced includes standard multiple choice questions, but also more complex items. In English students are asked to click on sentences in a paragraph that support an idea, and in Math they are required to manipulate graphs. Some questions will be graded by computers, others, like those answered in paragraph form, will require human grading.

Technology Upgrades

Stan Freeda works with the New Hampshire Department of Education. One of his jobs is to help schools determine if they are technologically ready for the Smarter Balanced test, which is to be taken entirely on computers.

“They get to decide how many sessions per day they’re going to give and how many days long is it going to take,” he explains. Because the test is adaptive and students won’t all be answering the same questions, they don’t all have to take the test at the same time. Schools can specify how many kids will take the test at once and how many days they will spread testing over.

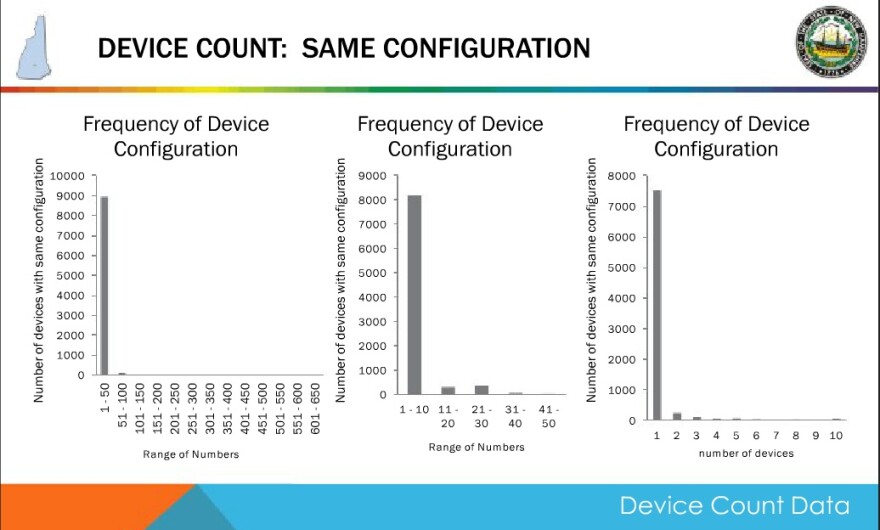

Freeda says surveys of New Hampshire schools find that not many have enough computers for every student. He says device counts show that “very few of them have over fifty. So we’re hardly one-to-one in most cases.”

This is the big challenge. Many of the schools that I spoke to for these stories are concerned about the need to invest in technology so that testing doesn’t drag out over weeks.

So even though the actual administration of the test should cost about the same or maybe a bit less than the NECAP test, many schools are spending scarce education dollars spent on more bandwidth or laptops.

That really bothers teachers like Penny Kittle an English teacher at Kennett High School. She says, “most districts are making these big cuts to pay for, what I see as a bad investment.”

Kittle is the kind of teacher who questions the value of any of the information gleaned from standardized testing. She prefers the idea of giving control of assessment back to teachers and schools, who have a more complete idea of what their students are capable of.

“We too often look at data and say, ‘3rd graders can’t read!’ when nobody sat down and asked those kids to read to them,” says Kittle.

But giving up the ability to compare students between districts and between states is a tough sell for education policy makers. So like it or not testing, and likely computer based testing, is here to stay.

Tougher Test, Higher Expectations

Change is hard. It’s a trope to say it, but no less true for being a cliché.

Back at our little focus group at the White Mountain Regional High School, students Imani Gaetjens-Oleson, Tyler Welch and Emma Portinari say they weren’t much impressed with the Smarter Balanced.

“I felt like the computer was a little more intimidating that paper and pencil was,” says Welch who appreciated being able to flip back and forth through the NECAP booklet.

“I saw a lot of people that were done so early,” says Gaetjens-Oleson, “and I talked to them later and they just said I didn’t know anything so I just clicked random things because I couldn’t figure anything out.”

Emma Portinari agrees, “I don’t mean to sound snobby but I’m in like High honors, so like me doing this I’m like how are people who like don’t know as much skills as I do, how are they doing this?” The others nod, and say they felt the same way.

Their Math teacher, John Wood, says the take away from the test is clear. “As opposed to just answering the question, they now have to know how to apply a formula, know how to use it, know why they’re using it, to answer a series of questions not just one,” Wood says.

If you helped to write the Common Core hearing an in-the-trenches teacher say that must do your heart good. the standards are all about raising expectations and one purpose of the testing is to drive those higher expectations.

And really, if you could write a perfect test, that could somehow distill into statistics how prepared for life a student was, no teachers would complain about teaching to the test. But it won’t be until 2015 when kids take this test that we learn if we have made a step in that direction, or not.