Hope on the Front Lines was a week-long series focusing on the people and organizations working to make a difference on the front lines of New Hampshire's opioid crisis. Produced by NHPR's Morning Edition team, host Rick Ganley and producer Michael Brindley traveled the state to meet people on the ground level of a growing epidemic, doing what they can to help in their communities.

Explore the Project:

Feature: Training a Community to Become First Responders

Feature: A Community's Center of Hope

Video: Addicts Helping Addicts at Hope for N.H. Recovery

Feature: Heroin Anonymous - Familiar Steps Fight a Growing Crisis

Interview: Advocating for the Kids of Addicts | Map: CASA Cases Involving Addiction

Feature: Filling the Treatment Gap for Pregnant Addicts

Feature: A New Approach for Soothing Babies in Withdrawal

Video: Concord Hospital's Musical Approach to Soothing Babies in Withdrawal

Story Map: Click the map pins to see story summaries, photos, and video from the series.

Training a Community of First Responders

Reported by Rick Ganley, Produced by Michael Brindley

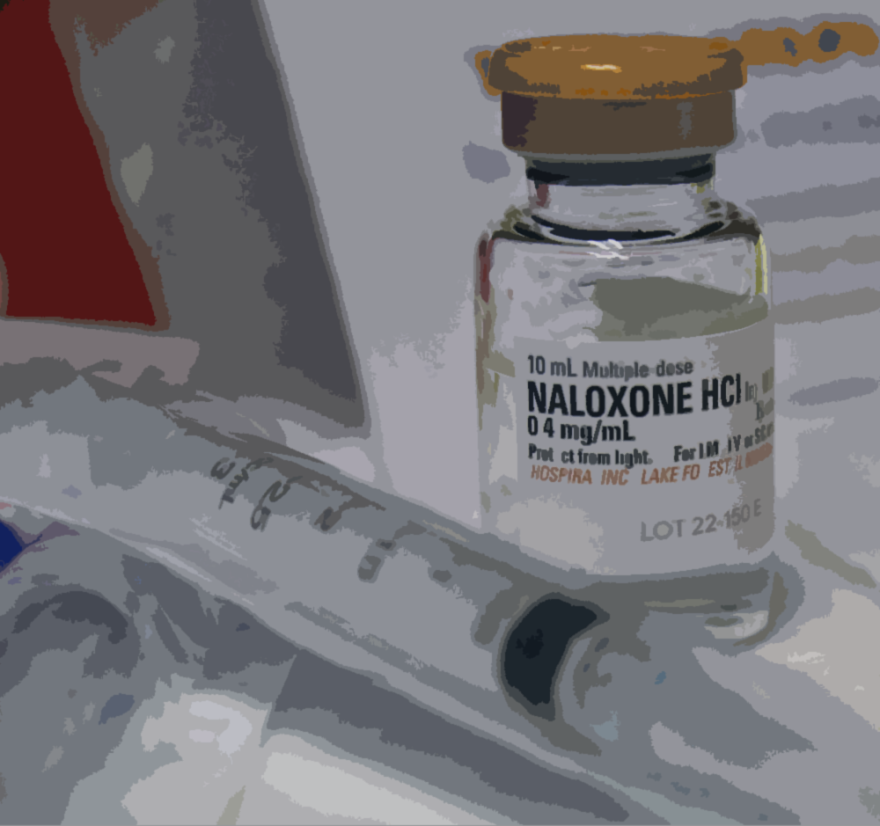

On a Saturday afternoon in Keene, a handful of people are learning how to use the now widely available overdose-reversal drug Narcan. It’s one thing to get it into the hands of those who may need it. And as I find out, it’s another to know how to use it properly.

Listen to the broadcast version of this story:

Tricia Wadleigh is with the Greater Monadnock Public Health Network. She demonstrates putting together a Narcan kit for the class.

“You put your thumb on the bottom. It’s got hash marks on the side, so it said half and half in each nostril. You don’t have to be a scientist here. So you’re doing about half in each.”

Wadleigh's holding a clear syringe with an atomizer, which turns the liquid into a spray. People here today get a free kit, but the training is also an opportunity for people like Bill Davis to ask questions.

"Does it work on suboxone and methadone?"

"Yes," Wadleigh says. "So they’re overdosing or used too much of those substances, this can help block those receptors in the brain.”

Later, I pull Davis aside, and he opens up about his own struggle with heroin addiction. A power lineman, he suffered a back injury on the job and needed surgery.

“After the operation, I got some pretty serious narcotics. I didn’t do the rehabbing like I should have. Once they cut you off the stuff…I was sick. I had no idea what hit me. I really didn’t know what opiate sickness was.”

Davis is now in clean and in recovery, and while he hopes he never has to use his Narcan kit, he still knows people who are actively using.

“Like they say, relapse is a part of recovery. Let’s hope they don’t relapse, because if I see somebody in an overdose, I’ll at least be able to give them some of this. I just don’t really want to see anybody die. If I can help, I will.”

The kits being handed out today are part of the 5,000 the state dispensed last fall, paid for through a federal grant.

Tricia Wadleigh, the trainer, has handed out more than 300 kits in the region since December. She tells me the people who come out these kinds of trainings are usually dealing with addiction issues in their lives.

“So these are the mothers who are knocking on their daughter’s door three times a night to make sure they’re awake. They’re the wives who are checking on their husbands multiple times during the day. They’re the children who are checking on their parents multiple times a day. The idea was to get the kits to the users, folks struggling with addiction, and then their closest circle.”

Wadleigh says she’s done nearly twenty trainings since December, mostly at local businesses, health care organizations, and public schools.

“And maybe we’re not necessarily dispensing kits all the time, but they’re definitely interested in the education. So we’ve had a little bit of uptick from folks who are interested. And we try to meet that need, whether it’s on a Saturday like this, or during the workday or after work hours.”

It’s obvious just how much of a need there is.

First responders with the Keene Fire Department tell us they’re seeing every day just how hard the epidemic has hit the region.

They’ve used Narcan more than fifty times this year; compare that to only about a dozen times during the same period last year.

MAP: Narcan Emergency Reponse Calls in Keene

“Narcan is nothing new to us. We’ve had it for a long time. But what you’re starting to see is what it’s mixed with. OK, you’re getting the heroin. What’s in that? It’s laced with fentanyl. It’s a way to make it cheaper for a better profit margin.”

'I've brought him back nine times. Nine times. It kills me every time I see him. This is happening to everybody. It's affecting everybody. You know somebody that's affected by this. You’re taking a step here to help people out.'

Jim Pearsall is the training lieutenant for the city of Keene, and he says that dangerous mixture means many overdose victims now need several doses of Narcan to be revived.

And Pearsall says they’re seeing the same people over and over again. And he tells the rest of the class about one of those people they’re seeing frequently; it’s someone he knew growing up.

“I’ve brought him back nine times. Nine times. It kills me every time I see him. This is happening to everybody. It’s affecting everybody. You know somebody that’s affected by this. You’re taking a step here to help people out.”

We’re learning CPR today as well. first responders say it’s not always enough to have a Narcan kit.

As we’re down on the floor practicing chest compressions, a call comes in: there’s a needle on a nearby street. Pearsall says that’s happening virtually every day.

“We need to be policing ourselves, policing our kids, say hey, don’t touch that. If something looks suspicious, call. We’re here.”

This is the second CPR/Narcan training hosted at the fire department this year; both organized in partnership with a local advocacy group: Keene Hates Heroin.

Jessica White founded the group last year, after losing several friends to overdoses.

“Addiction has been in my life, all growing up, I’ve had family that’s addicted in different ways. And some personal experience. So it’s kind of just a natural calling. I think I just realized there’s a lot of gaps in the community. And if you are determined, you can help bridge those gaps.”

'I think I just realized there's a lot of gaps in the community. And if you are determined, you can help bridge those gaps.'

The group holds community meetings, where people come together to talk about why people are using and how to support recovery. White sees Narcan training as one more way to help.

“Narcan is definitely not a solution. But if it’s used as a means to open up that conversation with more people, somebody walks in the door just because they want that training, at least I got them in the door, I got them engaged in conversation, and now they’ve been exposed to a wider mindset.”

And there was plenty of conversation. People share personal stories and hear first responders talk about what’s happening on the ground.

Diane Meagher is also here. She’s a school nurse in Keene, where officials recently approved stocking Narcan in schools.

“We’ve had incidents of staff, we’ve had incidents of students, we’ve had incidents of parents, so it’s just one more thing in our tool kit. And as our RNs, we’re sort of used to this delivery method.”

And Tricia Wadleigh, the trainer, tells me the sessions are also an opportunity to debunk some myths. Narcan can’t get you high and she’s seen no evidence to support the argument that making it more available would encourage users to push their limits.

Series Primer: How does Narcan Work? Click here to find out.

“There’s a lot of misinformation out there. There’s a lot of very personal opinions, very passionate personal opinions that might not be based in any science or logic, but it’s really hard to break those down. So being able to educate folks about a simple option to save a life is a really powerful thing.” This kind of training is happening all over the state.

Coaching Recovery

Reported by Rick Ganley, Produced by Michael Brindley

One way that people are trying to help make a difference in New Hampshire's epidemic of addiction is through recovery coaching, a peer-support model that's gaining momentum in the state. Coaches support those in recovery by helping access treatment and other resources, like finding a job and a safe place to live as they try to get clean.

To learn more, I recently joined about 40 people at a Recovery Coach Academy in a hotel conference room in Concord.

Listen to the broadcast story:

“My name is Kathie Saari, I’m from New Ipswich, New Hampshire and I pastor a church there.”

“Dave Simpson, full-time firefighter/EMT with the town of Pittsfield.”

“I’m Melissa O’Brien, and I’m from Nashua, New Hampshire. I want to jump on that bandwagon to really learn how to combat this epidemic.”

'This is an amazing person, someone who had some much to give and love. And he's gone...I really just want to know what could have stopped it because it's a waste.'

Everyone I speak to wants to help, but perhaps no one in the room is feeling a sense of urgency like Kyle MacDonald of Franklin.

“It’s unfortunate. I actually had a friend pass away just last night of an overdose. I got home after going to a recovery meeting, and I come to find out my buddy’s passed away. This is an amazing person, someone who had some much to give and love. And he’s gone. And we’re losing people like that every day.”

"When something like that happens you get a call like that, what’s your first thought?"

“I really just want to know what could have stopped it because it’s a waste.”

There are a lot of stories like that in this room, and a lot of close calls.

Like many here, MacDonald is in recovery himself and he’s taking this training as a way to help others who want to get clean.

“I can’t predict who or what I’m going to do with it. All I know is that this is something I feel that I need to do. I can’t really explain it better than that. It’s something that I need to do. And no matter what that looks like, I want my hand to be there for someone who wants to grab it.”

“There are so many people who want to do something to help and this is kind of a way to figure out how can I be a part of the solution.”

Cheryle Pacapelli is Director of Community Engagement for New Futures, an advocacy organization that has trained more than 200 coaches in the last year.

“We’re seeing family members, people who have lost children, or brothers or sisters. As well as people whose kids…this poor woman’s kid is in treatment in Arizona because he couldn’t get treatment here. He’s been there for a year.”

They’re seeing clergymen, EMTs, police officers, and even those on the other side of the law. Ginger Ross with the New Hampshire Alcohol and Drug Abuse Counselors Association shows me a letter she got from an inmate at the Concord state prison.

“He wrote me this passionate letter and he indicates that he’s six months sober and he recognizes the value in recovery. When he gets out in 18 months, he wants to be part of the recovery community to help others.”

Recovery coaches are not licensed by the state and do not provide clinical services.

This week-long training costs $100, and, Ross explains, it can be a starting point for those looking to get into the professional field.

“As a recovery coach, they will receive 30 credit hours that they can use toward their licensure of either a CRSW, which is Certified Recovery Support Worker, or if they’re pursuing a career towards licensed alcohol and drug counselor, they can use those credits towards that.”

And it’s not just New Hampshire where recovery coaching is growing, says Jim Wuelfing. He’s running the training, and helped write the academy’s curriculum.

“Universally, we understand that treatment works, but what we haven’t done that well as a society is support early recovery And that’s why you see the revolving door, both in treatment and in criminal justice. Recovery services are really growing everywhere.”

As the morning gets underway, there’s an open discussion with the class; the conversation veers into topics like ethics and personal biases.

Many in the room open up about their fears of getting emotionally invested in their subject’s recovery.

“I mean, how do you not take it personally if you’re working with someone and they just start spiraling into self-destruction?”

The answer? Avoid the expectation that your help will be received.

“The whole point of recovery coaching isn’t I’m right and they’re wrong. It is I’m meeting them where they’re at; to put your love and your compassion and whatever resources you have to share with your recovery on your table. Whatever the person does with that is up to them, it’s not up to us.”

The walls in the rooms are covered with easel paper from brainstorming sessions held during the week.

The tables are covered with cans of Play-Doh and bite-size candy; Kathie Saari, the pastor from New Ipswich, says the mood is often light.

“Never a dull moment in this class. There’s skits and things to help you get into the mode of learning and keep it there and retain what you’re learning. Amazing class. I highly recommend it for anybody.”

And everyone here has a different plan for what they want to do with this training.

Saari runs support groups out of her church, and plans to bring what she’s learned back there.

Dave Simpson, the firefighter and EMT from Pittsfield, says he’s here to learn how to help those who’ve hit rock bottom get on a path toward recovery.

“You know, studies suggest that within 24 hours of an overdose is when people are most open to help. And we’re there minute one.”

He says taking this class has opened his eyes.

“I think my ‘aha’ moment so to speak was speaking with my fellow classmates. In this class, the majority are people in active recovery. And to hear their stories, it’s just amazing how strong these individuals are.”

One of his classmates in recovery is Carolee Longley is Northfield.

“I’ve been one of the anonymous people that has been out there for almost 28 years being clean and sober behind the scenes.”

She sees the training as the start of her path toward working in the recovery field.

“We’re losing a generation. This is wiping out a generation. I have students I used to work with and some of them aren’t here anymore. These kids are dying way too soon. So I feel a personal responsibility to try do something about the heroin epidemic.”

And others, like Emily Duff from Lebanon, are here to help family members dealing with addiction.

She’s planning to bring back what she’s learned to the Upper Valley, where she says resources are scarce for those who need help recovering from addiction.

“I think it’s maybe lack of funding. A lot of people don’t want to deal with it. I don’t think a lot of people want to face that there is an issue. But it’s out there and we need the help.”

A Community's Center of Hope

Reported by Rick Ganley, Produced by Michael Brindley

We are continuing our look at a growing model of peer-to-peer addiction support by meeting the recovery coaches taking on New Hampshire’s opioid crisis in Manchester, where more than 100 people died of overdoses last year.

Despite those grim numbers, it’s a surprisingly positive atmosphere on a Thursday night at Hope for New Hampshire Recovery, a substance abuse recovery center in the heart of New Hampshire’s largest city.

Waking in, I see walls covered with messages of encouragement and support.

“You can always tell when somebody comes in like, ‘Hey, you having a bad day? What’s up??’ They get you out of it. Your other peers get you out of that.”

Kelly Riley is the recovery coach supervisor; there are about twenty paid coaches on staff here, along with another roughly fifteen volunteers. There’s a rotation, so there’s always at least one coach on call for those who come through the door or to respond to calls from out in the community.

I’ve only been here a few minutes when a call comes in: someone’s looking for help just a few blocks down the street at the city’s Central Fire Station:

'We've all done those things...steal, lie, cheat to get what we needed. So it's nice to be able to share that with somebody and say hey, you don't have to feel alone because we've all been there, we've all done that.'

“We, no matter what, as recovery coaches, we walk over there and get them. So we’re going to take a walk over there,” Riley says.

We step out into a city that’s been ravaged by the heroin and opioid addiction crisis. Walking along Pine Street, Riley explains this particular call is part of a new program – Operation Safe Station.

“You can go to any fire station and go there and ask for help,” Riley tells me.

“How many people have done that so far?”

“We’ve had at least 70 calls; not everyone has ended up with us. But we’ve kept several people. So as you can see, the ambulance is right there. This person has either overdosed or come close to overdose."

There’s an EMT waiting outside as we walk up to the fire station, and Riley explains her plan.

“We’ll bring him back and talk to him over there, start seeing what’s going on, how you doing, what’s your life like, what are you addicted to. OK, you stay here, I’ll go talk to him, see what’s going on…"

A few minutes later, she comes back out with a man in his early twenties; he’s wearing a tattered black t-shirt and jeans, and carrying his belongings in a duffle bag.

Listening to Riley talk to him, it becomes clear he’s been to the recovery center before.

“I remember you, I remember seeing you. You know, we can get you on the path. Just knowing that you just went there, you gotta feel a little bit better because you’re doing something for yourself.”

Walking back, the man opens up about his one year-old daughter. He wants to get better for her, he says, but he’s never been able to admit he needed help.

“Well, you’ll meet 100 other people who are the same way," Riley tells him. "It’s hard to ask for help.”

Back at the recovery center, Riley gets him settled in:

"I’m going to put you right over here. This is what we call the little cube. I’m going to get one of the other coaches. So just get comfortable. There’s coffee right there if you want a cup of coffee…”

He meets with a coach and they start mapping out a recovery plan.

The center is filling up quickly for tonight’s heroin anonymous meeting; looking around, it’s impossible to tell the difference between the coaches and the members.

And there’s a reason for that.

Like many coaches, James Holloway was once an addict. It wasn’t that long ago he was in the same place as those he’s now helping.

"We’ve all done those things – steal, lie, cheat – to get what we needed. So it’s nice to be able to share that with somebody and say hey, you don’t have to feel alone because we’ve all been there, we’ve all done that.”

Now that he’s clean, Holloway is helping others as a coach, but he’s also reconnected with his family and is able to spend the weekends with his daughters.

“The blessings that have come out of it are just like tenfold, compared to my life before,” he says.

It’s a familiar story here.

David Cote has been in long-term recovery for 25 years; he’s another recovery coach on staff.

“To be able to say been there, done that, it’s a very powerful tool. I wouldn’t be able to do this if I wasn’t able to share my story,” Cote says.

“The rule here is eighty/twenty. So we do twenty percent, and the member does 80 percent. So I’ll put them in front of phone, I will give them phone numbers, but for the most part, they’re the ones doing the calling.”

But finding treatment isn’t always easy; many of the people coming in don’t have insurance.

“Obviously, we want to help people when they need it, and that window of opportunity is very narrow. So if we can get them on a wait list and keep them involved and keep them active, that keeps that window open that much longer,” Cote says.

And the need keeps growing.

Video: Watch Kelly Riley and James Holloway talk about their experiences at Hope for N.H. Recovery

https://vimeo.com/169480439">Hope on the Front Lines: Hope for N.H. Recovery from https://vimeo.com/nhpr","_id":"0000017a-15e8-d736-a57f-17ef8f7b0001","_type":"035d81d3-5be2-3ed2-bc8a-6da208e0d9e2"}">

When the center first opened last summer, a few hundred people would show up in a month. Now it’s upwards of 2,000. Cote tells me about what it's been like to watch that growth.

“I have seen a lot more people come in, and a lot of young people come in, which is amazing because I figure if someone can come in at 20 years old or 25 years old and find recovery, how many years of misery have we avoided for them or have they avoided for themselves?”

Later, I meet coach Bryan Patriquin. He’s been in recovery for about five years.

“Most people don’t know what a recovery coach is. It’s just a term everyone throws around because that’s really what we do. We help coach, we encourage, we empower, we empathize with the individual who’s seeking help.”

In the back of the center, there’s a room called Amber’s Place. It’s a space in the building where members can stay while waiting to get into treatment.

'I figure if someone can come in at 20 years old or 25 years old and find recovery, how many years of misery have we avoided for them or have they avoided for themselves?'

Recovery coach supervisor Kelly Riley walks me through. There are mattresses are spread out across the floor; and it’s where the man we picked up earlier in the evening will spend the night.

“We have capacity for 16, and we were very close to that the day before yesterday. We had eight pickups, eight people come in."

How long do they stay on average?"

"We like to get you out between 3-5 days."

People are free to go – some leave, sneaking out the back door – but for those who stay, there’s always someone here to talk to.

“Because we don’t have any kind of funding, we rely on people to give their time to sit and listen to someone," Riley says. "You see so much of that. People just want to talk to somebody who’s not going to judge them.”

And, like others here, Riley is no stranger to addiction.

She’s in recovery, and lost her son to a heroin overdose.

“When I talk about it – and I talk about it a lot – I can get very emotional because it’s a very emotional thing. We’re so used to not showing our emotions. And people will be like, wow, I know what that feels like.”

Recovery coaching isn’t for everyone. Many get burned out.

David Cote, one of the coaches, says you’ve just got to focus on the small victories.

“It really is about, ‘I got somebody a phone number to a treatment center and he got on a wait list.' That’s something he didn’t have when he came in. Or I found somebody a safe place to live for the night."

And there’s good news for the center. This summer, it will move into a larger space in a former furniture building in the city, where there will be more beds and housing for those in recovery.

Heroin Anonymous: Familiar Steps Fight a Growing Crisis

Alcoholics Anonymous has become a well-known part of recovery, but now, Heroin Anonymous meetings are popping up all over the New Hampshire. The meetings are in large cities like Manchester and Nashua, but also in smaller communities where the addiction epidemic has taken a toll.

I’m in here in Newmarket, a town of about 9,000 people near the seacoast; the downtown is a string of quaint shops and renovated mill buildings, along the Lamprey River waterfront.

Kimberly Branch at a small, hole-in-the-wall restaurant. She works part-time here, one of her two jobs.

“Jonny Boston’s is a great little spot to be. It’s fast food cooked slow. It’s just an awesome little place. Good energy.”

There’s a steady stream of reggae music playing, as the lunch crowd shuffles in. We grab a booth, and before getting to her decision to start a heroin anonymous group here in town, she opens up about her own experience with addiction.

'When I came across heroin, I absolutely fell in love. And I wanted more of it because I didn't want to feel the pain I felt inside.'

“I started when I was fifteen. This was back in ’99. My dad had passed away and I started using everything I could get my hands on. When I came across heroin, I absolutely fell in love. And I wanted more of it because I didn’t want to feel the pain I felt inside.”

And after everyone she cared about had dropped her from their lives, Branch knew she needed to make a change.

“It wasn’t until I grieved with my own issues on the inside that I was able to realize this is not the life I want. I want to move on and do more with my life.

She’s now ten years sober, and between work and taking care of her two children, Branch is paying it forward by running weekly Heroin Anonymous meetings.

“My whole thing is to try and held the addicts nowadays. To help them realize that I did it, and I know you can do it. I really believe that with all my heart.”

Last fall, she reached out to a national Heroin Anonymous organization, and got a starter pack of pamphlets and key tags, which are used to mark milestones of sobriety.

And now every Wednesday night, she’s hosting meetings at the Newmarket Community Church.

“When I have my meeting, I like it to be comfortable. It’s in a little spot upstairs in the church. There’s couches in there, chairs. It’s very comfortable. It’s very relaxing. I like more of the peer counseling, but I do go by the twelve steps, as well.”

"Is it kind of modeled after AA?"

"It is exactly modeled after the twelve-step program, yes,” Branch says.

But, unlike AA, Branch says having someone who’s actually been down the path of heroin addiction makes all the difference.

“Because I have been there, I think it means a lot more than going to an AA meeting and they have no idea what it’s like to actually do heroin or be in that slump, that heroin slump.”

I wanted to hear from the people that go to these Heroin Anonymous meetings, so Branch offered to meet with members and use her cell phone to interview them.

We’ve agreed to only use only their first names in this story.

“Hi, my name’s A.J. I’m 23 from Rochester, New Hampshire.”

A.J. got addicted to heroin after getting hooked on prescription medication following an injury. He stole, lied, and lost the ones he cared about.

"Why are you going to Heroin Anonymous?" Branch asks.

"Well, I came to the conclusion that I can’t really live my life the way I have been. I needed to work on myself and this seemed like the place to do it."

Branch also spoke with a woman named Aubrey, a recovering addict who’s on her sixth time trying to stay clean.

Aubrey says the hardest part of recovery is the isolation.

“Most of the people I know around here are addicts or are recovering addicts. I can get it with one phone call. I feel like I’m sheltered. I just stay in my room because if I go out, I feel like I’ll end up doing something stupid.”

When Branch asks Aubrey why she goes to Heroin Anonymous, she says, “I like to listen to other peoples’ stories because it makes me feel better, like I’m not alone.”

Back at the restaurant, Branch says she’s run about 30 meetings so far, and each one is different.

“We have people come and go. I’ve had one person that I’ve sat there and talked to and I’ve had seven or eight people there that I’ve talked to. It’s up and down. You never know what’s going to happen. I have to show up every Wednesday at the same time and just hope that someone comes to hang out with me and talk about addiction.”

Those who do come to the meetings are in all stages of recovery. Some are court-ordered to attend the meetings, and Branch signs off on papers for them.

And sometimes people show up to the meetings high, but Branch doesn’t turn them away.

“They sit there, they nod out, whatever. It’s distraction for my other people who do want help. It’s a slap in the face and I’d rather they not come messed up. It’d rather they come clean and be serious about their recovery. It doesn’t always happen that way.”

And while she’ll point people in the direction of treatment, there’s only so much she can do.

“The only thing that’s going to get you sober is yourself. It’s when you decide that you’re tired of living the same way you’ve lived, in your addiction, and you want something different. You want something more.”

Branch is just one of the everyday people in town trying to help. Jon Kiper is another. He owns this restaurant, and joins us in our booth.

'I think the hardest part is that it's not like there are a bunch of addicts in line ready to get help...and the biggest problem is there's only so much we can do without any money and so few beds.'

He’s part of a community coalition called Newmarket Alliance for Substance Abuse Prevention. The group has held forums in town, and come up with ways to address the problem. Kiper got involved after he learned one of his employees was an addict.

And as part of the coalition, he’s learned getting people help isn’t easy.

“I think the hardest part is that it’s not like there are a bunch of addicts in line ready to get help. Most of them don’t want help. So we kind of got all geared up and it was kind of like, there’s a limited amount we can do. And the biggest problem is there’s only so much we can do without any money and so few beds," Kiper says.

Kiper says it’s frustrating to see that first hand.

He says former employee who was using couldn’t afford rehab. And after going to jail for three months, he’s back out and using again.

“And so the state ended up paying, what, $6,000? What did three months in jail do? Nothing. It’s not like there’s a lack of money, it’s just the resources are being spent in such an illogical way.”

Still, the coalition is doing what it can.

Branch says it’s raising awareness and creating resources within the community, like the Heroin Anonymous meetings, and for others here in Newmarket affected by the crisis.

“They’ve started a support meeting for the people, the family of the addicts, so there’s also that option in town. When we have an issue arise, we try to solve instead of just turning our heads to it.”

Advocating for the Kids of Addicts

By Rick Ganley

The drug crisis is taking a toll on New Hampshire’s families, as more and more parents accused of abuse or neglect are dealing with addiction issues.

Court Appointed Special Advocates of New Hampshire, or CASA, says nearly 70 percent of its cases last year involved families affected by substance abuse. Many of those cases involved parents addicted to heroin and opioids.

CASA volunteers advocate for abused or neglected children in the court system. Jennifer Westover of Concord is one of those volunteers; she’s worked on two cases that involved parents struggling with drug addiction.

She spoke with Morning Edition's Rick Ganley about her role in those cases.

Listen to the broadcast version of the interview:

How did you get involved with CASA?

I have worked in the court system before and worked for an administrative judge in the past, so I’m familiar working with the public when they’re not in the best times of their lives. About four or five years ago, I decided that I was not going to work and I was looking for something to do. I was looking for something that was rewarding and would give back to the community, but I also wanted a challenge.

What do you generally do with these children and these families? What’s your role on a daily basis?

My objective is to get in there and really see what’s going on so I can tell the judge. DCYF is also doing this, hand in hand. I give my perspective on how they’re interacting with their child.

They want you as another set of eyes.

Right. When I’m writing my report, I’m thinking if I was that child, what would I want to tell the judge about my parents. I want them to straighten up and fly right and take care of me, but I have to go into specifics, whether they’ve attended all their counseling meetings or if they’ve had negative drug screens. Or they didn’t, or they got arrested. I’m telling my story from what I’ve gleaned, going to the home and visiting them. We have meetings where we go to where everybody comes to the table and talks about their progress.

As an addict, she just wasn't making the right choices. Her child was not the most important thing in her life. That was kind of forgotten.

And you’ve volunteered on two recent cases that involved parents struggling with addiction. What’s your role in those types of cases?

Initially when you get started on the case, it seems like they’re not really present. They’re more concerned about getting their next hit. They generally don’t know understand who I am for awhile. They just know that I’m always there and I tend to focus on cheerleading them, to encourage them to hopefully make the right choices.

In one case, I got to watch a parent change and fight her addiction and win and become a totally different person in the end, a wonderful person, not that she wasn’t as an addict, she just wasn’t making the right choices. Her child was not the most important thing in her life. That was kind of forgotten. I wasn’t sure it was going to have a nice outcome, it wasn’t clear from the beginning that they were going to succeed in addiction recovery. But then you see them change over a period of months. They start looking at you in the eye. It’s a gradual process. They may screw up, but in the end it was very rewarding.

At the very end, to have the parent come up to me after it was all said and done, after she was reunified with her child, to come up to me and the DCYF worker and talk normally, talk about the kid, talk about what’s going on, it was wonderful. Such a different person from when we began the case.

Map: Click on each county to see how many of CASA's cases involved substance abuse in 2015.

For a better experience on Mobile, turn your devices sideways. (Data courtesy CASA of NH)

Are there differences in the cases you’ve see when it comes to addiction?

I’ve been involved in a case where there was a family involved outside of the parents, and one where there was no family involved. And it was a radically different outcome. Having the family involved, being there every day. We’re not able to be there every day to prod the parent to make the right choices. The family being involved and giving them rides, getting them to the doctor, made a remarkable difference in my eyes. The one case where the family wasn’t involved in ended in termination of both parents’ rights. The kids were adopted, which turned out happily for them since I’m pleased with where they are, but it’s also very sad that they’re not with their parents and their parents didn’t succeed.

Through the cases you’ve seen, what do you take away? Is there anything you’ve learned about addiction?

Just that it’s really sad when someone becomes an addict. It’s just sad they every introduced that into their lives for whatever reason. I’ve learned that some people become addicts because they’re self-medicating. Being involved with someone who’s an addict and then seeing them change into someone who’s perspective isn’t for the drug definitely changed. In my private life, I’ve never been involved with someone who’s an addict, so it was very eye opening. I have to mention that CASA is wonderful about giving us education. It’s been a learning process for me. I’m exposed to people who are addicts, along with being required to get continuing education every year. I’ve focused in on drug abuse because that’s what my cases were about.

You’ve gone through two cases in a period of four years. There must be a huge need.

Yes, there are not enough CASAs at this point to cover all the cases in the state of New Hampshire. There’s a very big need for people to become CASA volunteers. I think people would really enjoy the experience. It’s a challenge, but very rewarding as well.

Filling the Treatment Gap for Pregnant Addicts

Reported by Rick Ganley, Produced by Michael Brindley

Advocates say one of the biggest gaps in the state is access to addiction treatment for pregnant women. And that’s where two women working in the medical field want to step in by opening a residential treatment facility for up to eight mothers and their babies in Rochester.

But as they’ve discovered, filling that need is no easy task.

“This is the living room here, and this will be where the women will have group counseling sessions with our clinical director.”

Listen to the broadcast version of this story:

Dr. Colene Arnold walks me through what will be the home of Hope on Haven Hill. It’s a spacious farmhouse, and Arnold knows it well: she’s lived here since 2004 with her husband and two daughters.

“It’s a beautiful, Greek revival, 1850s home," Arnold says, "And we’ve loved living here. But I’ve always felt it was meant for something greater, something bigger.”

Arnold will lease the home to the non-profit at below market value, which means she and her family will have to find a new place to live.

And she admits that took a bit of convincing.

“He was really not on board and my kids weren’t, either. They love this home, too, and they really didn’t want to leave. But through the process, my husband has definitely come on board, and my girls have also come on board. So that was the first hurdle we had to mount.”

Arnold works as an OB-GYN in Dover, and will serve as Hope on Haven Hill’s executive director when it opens later this year. As we continue our tour, she explains the goal will be to admit women when they’re pregnant and still in active addiction.

“So they’ll stay throughout their pregnancy. And then our hope is to be able to keep them for six months for up to a year postpartum, where that is such a huge risk for relapse time for pregnant women. Giving them a stable, nurturing home here with the therapeutic support they need is really going to sustain their recovery.”

She says expecting mothers will receive medication-assisted treatment, using methadone or buprenorphine, to get through their pregnancies. It’s an idea Arnold developed with Kerry Norton, a registered nurse and mother of three children, two of whom are in recovery.

Norton is here on the tour this morning, as well, where some areas of the house are still off limits.

“So that room we’re not going to show you because it is currently one of the daughter’s rooms. It’s going to be a therapeutic play room for the babies and moms."

'Postpartum is a critical time and we're going to give them lots of support.'

It will also be a space where mothers will have access to around-the-clock support.

Norton says programs like this help alleviate a common fear of pregnant women: that they’ll lose their children if they seek out help for their addiction.

“Families that have babies, it’s a crisis for people that don’t have a diagnosed substance abuse disorder or any other type of disorder. So you add substance use disorder to it, it definitely is…postpartum is a critical time and we’re going to give them lots of support.”

There are options out there: roughly 20 percent of the state’s substance abuse treatment facilities offer specialized care for pregnant or postpartum women, according to a 2013 survey. But even though state-funded programs must prioritize care for pregnant women, there are wait lists.

“I have calls, messages, and emails every day, from all varieties of ways from all sectors of everywhere asking me for help. It’s a crushing need right now. And it’s foremost in my head every day that the need is huge.”

“Unfortunately, being pregnant wasn’t enough for me to stop. I couldn’t stop for anybody.”

Abi Lizotte was the inspiration for Hope on Haven Hill. It was about this time last year when she was eight months pregnant, homeless and addicted to heroin.

“A lot of people begged. And I wish that I could have, but there was nothing strong enough, no one strong enough for me to stop. I don’t remember my pregnancy like most people because I used the whole time.”

She’s now seven months clean, but says at the time, it was easier to keep using than find treatment. She attempted suicide several times.

Kerry Norton met Lizotte at her first prenatal appointment.

“From January to June, we weren’t able to get her into the level of care that she needed for many different reasons, but basically because of wait lists and barriers.”

Finally, at eight months pregnant, Norton found her a spot.

"It was an hour and a half away from where I live, and after I left her, I cried like my entire way home. In my head, I could not even believe that this was the only thing we could do for the enormous amounts of women we have and know need this care.”

Lizotte’s story has a happy ending: her son, Parker, overcame the withdrawals he was born with due to her addiction, and is now nine months old.

“And he’s in like 18 month-clothing and walking around at nine months old, which is weird. But he’s doing great. He’s happy, he’s super, super healthy.”

'In my head, I could not even believe that this was the only thing we could do for the enormous amounts of women we have and know need this care.'

Seeing a need, they got to work last fall, but soon realized making this a reality was easier said than done.

One of the first hurdles? Spending two hours before the zoning board to get the OK to open a residential facility in an agricultural zone.

“We had some abutters who had some concerns and they were all addressed. We were very impressed with the system and the entire zoning board and we were allowed to have eight women and eight babies.”

But as Arnold, the executive director, says, after filing for non-profit status in November, it only got more complicated.

“So we need to come up to code with a lot of capital improvements that need to happen. We’ll be a level 3.5 facility here in New Hampshire, so for that, we have to have a sprinkler system in the home. So that’s going to be a $10,000-$20,000 investment.”

The home also needs a commercial grade septic system, though Arnold says she’s exploring hooking up to Somersworth’s sewer system, which could benefit surrounding businesses.

“So we’ll do the capital improvements and then we have to do licensure for the residential facility. I hear that’s an ordeal to be able to get done, so that’s going to take time. And we can’t bill for our services until we’re licensed. So until we can get that done, we do need state support to be able to get open and start running.”

And the status of that state funding is the biggest unknown.

Hope on Haven Hill applied for a $450,000 grant from a pool of state money that would have expanded addiction treatment for low-income or homeless pregnant women and mothers. But the Department of Health and Human Services never awarded the money because it says the two applicants – Hope on Haven Hill and the Cynthia Day Family Center in Nashua – didn’t meet the criteria.

A department spokesman says it’s re-examining the request for proposals.

'You know, if it's an emergency and a crisis, send out the people to get us open because we're here and we're ready to help people. Every step of the way has felt difficult.'

Still, Arnold says she’s optimistic, after state officials, including the head of the Bureau of Drug and Alcohol Services and the state’s new drug czar, toured the home last month.

“We did get an email back that they were looking at a variety of ways to fund our program, as well as any others that might work with pregnant women with substance use disorder. We don’t know exactly how that’s going to happen and we don’t know what the time frame is."

Arnold says she’s hoping to be open by the end of the summer.

In the meantime, they’re still working their regular jobs, and in their spare time, writing grants and fundraising. The program has raised nearly $80,000 since December.

Still, Norton says she can’t help but feel frustrated over what she says has been a lack of guidance from the state. She recalls the message from leaders in Concord to treat this as an all hands on deck emergency.

“And we took that literally and we did it, but I feel like there’s a whole…you know, if it’s an emergency and a crisis, send out the people to get us open because we’re here and we’re ready to help people. Every step of the way has felt difficult.”

And Abbi Lizotte, the inspiration for Hope on Haven Hill, is now one of its biggest advocates.

She believes in the program because of its plan to focus on addressing the root causes of addiction.

“They know how imperative it is to actually take a look at what it was that got you to start using so you don’t have to go back to that. Because if you don’t look at it, relapse isn’t an option, it’s inevitable. It will happen.”

A New Approach for Soothing Babies in Withdrawal

One impact of the addiction epidemic has been a skyrocketing rise in newborns experiencing withdrawal after being exposed to opioids in the womb. At Concord Hospital, caregivers are working with these families, and trying to ease the transition into life for these little ones.

“Oh! Such a nice face!”

I’m on a tour of the Family Place, the maternity center at Concord Hospital, and my guide – center director Barbara Pascoe – can’t resist picking up one of the newest arrivals.

“I think what’s so incredible is you think of a year in adult life and you really don’t change much. And then you think of a year in a newborn’s life. It’s phenomenal. Days, hours. It’s just incredible,” Pascoe says.

“Every week they look a little different?”

“Every week.”

Pascoe has been working with colleagues here at the hospital on how to make the transition to life easier for babies born with neonatal abstinence syndrome, or NAS.

“One of the things we have for NAS babies is…they look like caterpillars. We pop them in and it helps them self soothe. What’s that thing called? A woombie!”

'I think what's so incredible is you think of a year in adult life and you really don't change much. And then you think of a year in a newborn's life. It's phenomenal. Days, hours. It's just incredible.'

Last year, 56 infants exposed to opioids were born here; and so far this year, there have been 26.

“Ten years ago, if we had one or two of these children in a year, it was a very big deal for the staff,” Pascoe says.

The withdrawal process that can be traumatic for babies; they cry inconsolably and often can’t sleep.

“To watch a baby go through this is very…it’s painful," explains Tena Ferenczhalmy, the hospital’s neonatal nurse educator. "And, trust me, the guilt that these parents’ feel is palpable.”

“We’ve had babies who’ve gone upward of 24 hours with no sleep whatsoever, which we all know is not normal for a baby. A level of irritability. There can be a lot of GI symptoms, as well. So there can be nausea, vomiting, diarrhea.”

As the hospital saw more of these babies, the staff started experimenting with ways to soothe them.

Pam Tyrrell gently plucks the strings on her harp; she’s a certified music practitioner in the hospital’s therapeutic arts department.

She performs under the name DeLuna, and when she plays for NAS babies and their families, she starts with something slow and calming.

“And then if it seems the baby is comfortable with that, I may pick it up to more of a heart rate rhythm because babies’ hearts are so fast, so I may pick it up," she says.

“A lot of the things that I hear from the nurses and the mother is my baby just had a full feeding. It’s the first time my baby has actually gone through that. And that’s huge. That to me shows there’s a great comfort there.”

And babies may hear something different, like a Native American flute played by Amy Sarasvati, another certified music practitioner at the hospital.

“We are watching their breathing. We are watching their reaction. We are tailoring our service really to what’s happening for them. There’s a big difference between performance and therapeutic music.”

The hospital has also been offering Reiki and aromatherapy, delivered through oils with scents like peppermint and ginger soaked into cotton balls; babies, they tell me, are particularly fond of lavender.

Video: Concord Hospital's holistic approach to treating babies with neonatal abstinence syndrome

https://vimeo.com/169480709">Hope on the Front Lines: Concord Hospital from https://vimeo.com/nhpr","_id":"0000017a-15e8-d736-a57f-17ef8f7b0001","_type":"035d81d3-5be2-3ed2-bc8a-6da208e0d9e2"}">

Alice Kinsler, the hospital’s therapeutic arts director, says they’re able to actually see how music and scents help.

“If the baby is being monitored on a heart monitor or their vital signs are being monitored, we can see if their heart rate goes down. The musicians understand how to use their music to bring a heart rate down noticeably and we can see that on the monitor.”

Still, these soothing techniques are only complementary to the babies’ medical needs.

“We treat them with morphine, and they can wean off in a period of eight days, ten days, and go home like a normal newborn.”

Barbara Pascoe, the Family Place director, says it’s during this critical time when nurses offer support and guidance to mothers, some of whom are still using illicit drugs.

“We have this very little window of time where if a mother is going to make a change in her behavior, she’s going to do it when she has a baby because there’s a new little person that’s depending entirely on her.”

Many of the mothers go into treatment prior to birth, but maintenance drugs like methadone can still lead to NAS.

'All of us have probably made decisions in our past. But whenever you realize that you made a bad decision and you've actively on a path to do the right thing, then let's support that instead of continuing to keep it in the shadows and make it something dirty.'

In the best-case scenarios, Tena Ferenczhalmy says, the hospital’s treatment begins prior to birth with pre-admission meetings.

“A lot of these families are fearful that we’re going to remove their baby from them as soon as it’s born, and we’re actually modeling and mimicking the exact opposite. We know that babies, during withdrawal, have the best outcomes whenever they have a high level of interaction with their biologic parent.”

And developmentally, outcomes for NAS babies are positive, though they’re all referred for early intervention services as a precaution.

Ferenczhalmy says babies treated with morphine aren’t at a higher risk for drug abuse later in the life, something parents are often worried about. But mostly, she says the hospital works to get rid of the stigma for these families.

“All of us have probably made decisions in our past. But whenever you realize that you made a bad decision and you’ve actively on a path to do the right thing, then let’s support that instead of continuing to keep it in the shadows and make it something dirty.”

Of course, it’s not always easy.

Back at the Family Place, I talk with Pascoe about how complicated many of these family situations can be.

“I think the most challenging situation for us would be one where the mother has an issue and she hasn’t shared it with her family or her partner. And then we get a lot of questions about why is the baby still here and because of patient confidentiality, we can’t share that. And I think that the mothers are really selling themselves short in terms of the support of they would have available to them.”

"Have you seen circumstances where there is multiple members of a family in addiction?"

"Absolutely. And I think that’s what makes it really important that we treat these patients and give them the skills they need because when they go back out into the community, they may be going back out into a situation that isn’t conducive to the kind of care that we’re providing or their ultimate goals.”

And that’s why the hospital keeps the care going for the mothers after they’re discharged, offering lactation courses and a post-partum emotional support program.