New Hampshire officials are working on an application for a federal Race to the Top Grant for Early Childhood Education. If the state is selected in this round, it could receive up to $37.5 million dollars to support initiatives to improve childcare and preschool programs all over the state. While there is growing interest in pre-k issues the challenges standing in the way of better or more affordable childcare are daunting.

There’s a study that people in the area of early childhood education love to bring up when they want to show how important the years from birth to Kindergarten are.

“Nobel Laureate James Heckman has done some of the most cited work out there,” says Laura Milliken of Spark NH, a group created by Governor John Lynch to serve as the state’s early childhood advisory council, “[Heckman] says any dollar invested in early childhood has a $7 to $10 dollar return on the investment.”

This is the basic argument for investing in pre-k. They say it’s during these years that the first signs of a gap between privileged and underprivileged kids start to form, and dealing with it early is much cheaper than trying to create programs that will re-engage jaded high school students, or train up college dropouts. “We’re literally building the architecture of children’s brains,” explains Milliken.

“It’s like a house, it’s built from the bottom up and it’s either a sturdy or a fragile foundation,” adds Jackie Cowell, who directs Early Learning NH, a non-profit that does training for childcare providers, and advocates for expanded pre-k.

Racing For Race To The Top Dollars

Cowell and Milliken two work with state officials who are racing to finish a grant application by mid-October. These Race to the Top Grants are comprehensive

“Rhode Islands’ grant was 300 pages of narrative and 700 pages of appendices,” says to put it mildly says Deborah Nelson, the director of Head Start programs in the state, “I’ve been working on grants my entire adult life, this is the first federal grant I’ve ever been involved in that has no page limit.”

More than 30 states will vie for four or five awards.

NH’s grant isn’t done yet, but the officials writing it say they would spend that money on initiatives that would help improve the quality of daycare and preschool programs.

First up, they want to create a ranking system for the 950 licensed childcare programs in the state. Programs would get stars for things like having staff trained in early childhood Ed, having good outdoor play space, and evaluating children’s development once a year. Where the programs fall on the scale would determine how much of the grant money the programs would be eligible for in subsidies.

They also want to build a network that will provide face-to-face training for childcare workers, in hopes of showing more “marginal” programs what good care looks like.

And they want to create a data system that will feed into the public schools, helping teachers know more about the needs of new students as they enter the school system.

“$37.5 million can go a long way to building those systems. It will give us a lot of clout to build things that otherwise will take us another 15 years at least,” says Nelson.

Envisioning Quality Care

Basically, the state wants to build a system that helps programs get better, and be more like Live and Learn, a family-run day care in Lee that’s been around for four decades, that many hold up as an example of quality day care. They take care of around 70 kids, from infants to kindergarteners, and are accredited by two nationally recognized early childhood organizations.

By all accounts, it’s one of the best programs in the state and it all started out of Johanna Booth-Miner’s home. When she started in 1974 she charged $6.50 a day and for an extra $3.50 she would take children over night.

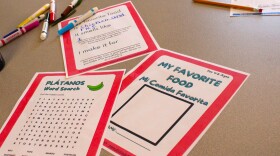

They’ve come a long way since then. Now, kids at Live and Learn are working the skills that will be their foundation once they hit school.

Booth-Miner explains that the children play in and around a learning garden where “from planting the

bean, to seeing the root, to seeing it grow, to seeing the flower, that’s science in real life.” To practice early math skills “we count how many steps we’re taking,” and they learn literacy concepts because “inside, if we have print in our world, we’re learning that that print has a meaning and that everybody who looks at it can get that meaning.”

Children at live and Learn are getting outside every day, all year long. “We celebrate international mud-day, in June, when children all over the world are jumping in the mud.”

They have a variety of stimuli, from a musical set of pots and tank to bang on to hamsters and guinea pigs in every classroom, that are used to teach empathy to toddlers.

The Fiscal High-Wire

Live and Learn is fully enrolled and has a waiting list, but even somewhere like this, finances are tight. Daycares everywhere walk a fiscal high-wire, attempting to keep care affordable, while still trying to offer high enough wages to attract qualified care professionals.

Booth-Miner tries to keep her prices down, because she’s seen how hard it is for families to afford childcare, but it’s hard. She charges around $250 to $300 dollars a week – depending on the age of the child – which is a bit above the state average. Her lead teachers earn between $27,000 and $32,000 a year, plus benefits. Compare that to the New Hampshire average of a little more than $20,000 dollars a year.

To make that work, the margins are thin. During the low period in the summer they make payroll with credit cards, and the building needs a new roof that it’s not getting.

“I do have two mortgages. We put pots under where it’s leaking, we put Tyvek on the roof… it’s not the best answer,” says Booth-Miner.

Booth-Miner’s daughter, Sarah Miner co-directs Live and Learn with her mother, as well as teaching early childhood education at the Nashua Community College. She explains that it’s very difficult to hang on to professionals, “We’re teaching kids at that most critical time of life, but if we’re working for no money, no support, and you walk out the door and everyone’s like, ‘oh you babysit, that’s what you really do?’ It doesn’t make people want to stay!”

And these expenses are tough to get around since it’s the people working with the kids that make or break a day-care. “We’ve seen quality programs in a basement,” says Sarah Miner, “and then you go into the best-of-the-best buildings, and you’re thinking oh no, I’m sorry kids have to spend their days here.”

Even with what are often seen as eye-popping child-care bills, ask most in this business and they will tell you that they are barely making money.

Developing Early Ed Focus?

Quality child-care is simply expensive: you need a lot of adults per child to make it work. If pre-k is going to improve in New Hampshire, this is the nut of the issue, and the state officials writing the Race to the Top Grant, realize that.

“If you’re asking somebody who’s been through 4 years of college to work for $10-$12 an hour, it’s simply not going to happen,” says Ellen Wheatley, Administrator of the Child Development Bureau at the state department of Health and Human Services. “We want them to be willing to stay and we want to pay them to stay. So that’s something we can do is we can have incentives for highly qualified teachers to stay in early childhood classrooms.”

But the grant isn’t written yet, and what form any incentives would take hasn’t been hammered out. And of course, New Hampshire will be facing healthy competition from other states, so this money is hardly assured.

Nevertheless, those working in early childhood education seem to think this issue isn’t going away.

Spark NH was formed by executive order barely two years ago, and Laura Milliken says she now feels a momentum growing behind the issue. “The evidence is very strong, and I think people are starting to understand,” she says, “there’s been a real lack of understanding of how important early childhood is to the rest of a person’s life and frankly to society.”

Jackie Cowell sees evidence of a national shift towards a new emphasis on early childhood in the rhetoric of the executive branch. In his last State of Union Address President Obama said that access to high quality preschool for all students should be a priority. “There seems to be a national conversation that wasn’t there before, and there certainly is a state conversation, so we’re very hopeful,” says Cowell.

So should the state miss out on the grant, this is an issue that seems unlikely to slip off the radar.

New Hampshire Early Education Facts

- Total children in one and two-parent families, with parents in labor force: 57,243

- Total Number of Childcare slots: 47,505

- Licensed Childcare Centers: 950

- Licensed Family Child Care Homes: 302

- Average cost of child care in a center for infant -- $11,440/yr; 4-year-old -- $9,100/yr

- Average cost of child care in a home for infant -- $8,528/yr; 4-year-old -- $7,800/yr

- Child care workers: 2,570

- Average salary for child care workforce: $20,420