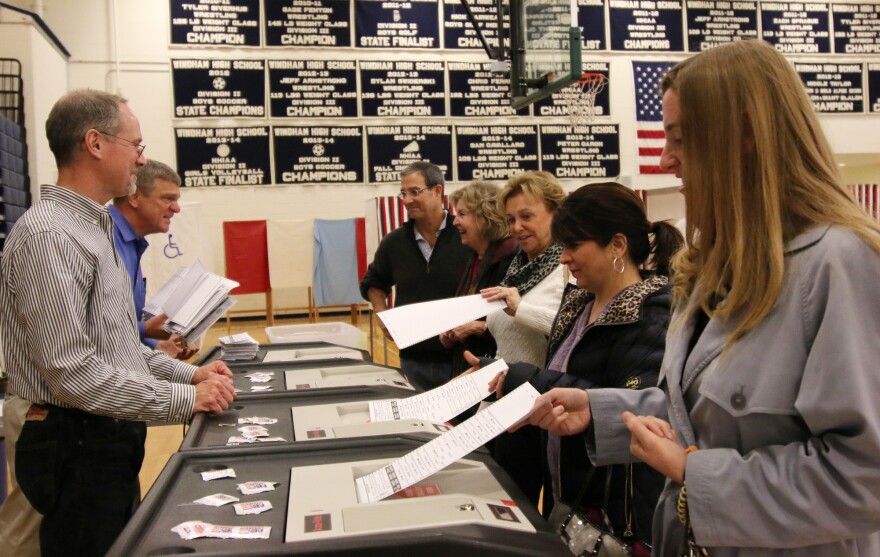

New Hampshire’s primary is just five weeks away, and state election officials are anticipating record turnout. There’s something else on their minds too—this will be the first presidential primary with the state’s new voter ID law in place.

The law, which passed three and a half years ago, was part of a wave of stricter voter laws pushed by Republicans across the country. How it plays out on Primary Day is still an open question.

Folks like Kerri Parker, the town clerk in Meredith, have been planning for that day for a while. Parker remembers when she and other election officials got together to learn the new state voting rules.

They went through the procedure step by step. But the main direction Parker says she and her colleagues got that day: Try not to make any voters mad.

"That's what we were told by the Secretary of State’s office," Parker says. "That you don’t want to get into a screaming match with them."

Though New Hampshire's voter ID law has been on the books since 2012, February 9th will the first time it will be in place for the state's presidential primary, when many of new or infrequent voters show up. Chances are, lots of them won’t know the rules.

Here’s how it works: When you show up at the polls, you’ll be asked to show identification– like a driver’s license or military ID. If you don’t have one, you’ll have to fill out an affidavit, swearing you are who you say you are. Your local election official will also need to take your photograph. Do all that, and your vote will be counted.

But it's a far cry from the days when a New Hampshire voter could just tell the clerk his or her name and walk into the voting booth.

"Most people are not as informed as I’d like them to be," says Parker. "So then they turn around and don’t have (an ID) and then for us to say, 'You have to have it and you have to sign this form.' And then, if they still don’t have it, then we have to take their picture. So it’s going to be a challenge, I think."

It’s not just election officials who are concerned. Advocates at the ACLU and the League of Women Voters will be monitoring what happens on Primary Day, making sure voters know their rights.

Joan Flood Ashwell is election law specialist with the League of Women Voters New Hampshire, and says laws like this risk pushing voters away—especially students, people of color, low income voters, the elderly who are less likely to have a drivers license.

"It doesn’t add anything to security or anything like that, and it’s basically a barrier to voting," Ashwell says.

But while some say laws like New Hampshire’s suppress votes, others say they’re necessary to prevent voter fraud.

"There is always this tension that takes place between trying to make voting convenient and trying to make sure that fraudulent activity doesn’t take place," says Dave Scanlan, Deputy Secretary of State. "So, the more you try to knuckle down on preventing fraud, the more difficult you’re going to make it for voters to participate in that process, and vice versa."

Scanlan says the number of people who actually show up to the polls in New Hampshire without proper ID is consistently less than 1 percent. He says it’s hard to say that any of them intended to commit voter fraud.

"Those people forget their ID at home, some protest the ID law going into effect. So, I think based on that, the actual percentage of voters that are trying to commit fraud, successfully or not, is really pretty small."

Scanlan says he knows of only one potential voter last election who chose to walk away instead of doing the whole affidavit and photo thing.

For those who do go that route, there’s a follow up. Soon after Election Day, Scanlon’s office will send you a postcard, to make sure that was really you. And then you’re supposed to respond.

If you don’t respond, the attorney general’s office will look into it. NHPR reached out to that office, but we couldn’t find any public cases of fraud stemming from the voter ID law.

So how many of those challenged voter affidavits will be floating around after the upcoming presidential primary?

Again, hard to say. Data from the 2014 elections obtained by NHPR shows inconsistencies in the number of voters showing up without proper ID from town to town -- even in towns with similar numbers of voters. That could have to do with discretion in how the law’s applied.

In Durham last year, 43 voters showed up without IDs and filled out affidavits. Chris Regan, an election official there, says that could be college students registering that day, or older people without licenses, or a bunch of conscientious objectors to the law.

For every added step to voting, he says, the fear is longer lines.

"You always have the question that, if the lines get backed up too much, do certain people make the decision ‘I just don’t have time to go through the process,' " Regan says.

He says he and his colleagues are still pretty at sea as to how it’s all going to work.

"All we know is that we have Polaroid cameras," Regan says. "We don’t know how much film we’re going to get. It’s going to be a real wild guess."

Election officials from across the state will meet one for more training on the law in a couple of weeks. Then, it's show time.