For years, Chris Clough prescribed more pain medication than almost anyone else in New Hampshire.

Along the way, state regulators say, he broke nearly every rule in the book.

Clough, a 41-year-old physician assistant for the state’s largest chain of pain clinics, failed to warn patients of the risks of opioids. He failed to screen them for addiction or mental illness. He disregarded drug screens that suggested his patients were abusing their potent medications.

Clough’s prescribing often defied explanation. He would start patients on high doses, and when that didn’t work, he prescribed more - in some cases, again and again, without documenting the reason.

When the New Hampshire Board of Medicine finally banned Clough from prescribing oxycodone, methadone and other drugs last month, the ruling quoted an expert witness who said Clough showed no “pharmacological or other skill whatsoever” in managing his patients’ medication.

Clough’s troubles with the medical board began more than two years ago. By the time the board released its 18-page final order, the abuse of prescription drugs and heroin had become New Hampshire’s top public-health concern. Clough’s case is an extreme example. But its resolution comes at a key moment in the state’s response to the opioid crisis, as policymakers turn their attention to a root cause: the prescribing habits of physicians, nurses and other clinicians.

On Wednesday, the Board of Medicine will hear public testimony on Gov. Maggie Hassan’s request to adopt emergency rules for opioid prescribing. The proposed revisions would replace the board’s current recommendations with a lengthy set of requirements.

Under the new rules:

- anyone authorized to prescribe opioids would have to take a course in pain management and controlled substances every two years;

- providers would be required to check the state’s prescription drug monitoring program before starting a patient on opioids;

- prescriptions issued by emergency room or urgent care providers would be limited to a five-day supply;

- patients who take opioids for chronic pain would be subject to annual urine tests, and those most at risk of abuse would be tested every month or two.

Opposition at Wednesday afternoon's hearing is expected to be vocal. Since a draft of the proposed rules became public in early October, the board has received more than 100 comments from members of the New Hampshire Medical Society, almost every one of them negative.

Much of the criticism was directed at Hassan’s initial request for emergency rules, without the usual public input and debate. But there was plenty of concern about the specifics of the proposal, as well.

David Strang, who chairs an advisory council to the state’s prescription drug monitoring program, said in a letter to the board that emergency room physicians would ignore a requirement to collect information on every patient’s substance abuse, mental health and “psychosocial” history before prescribing opioids.

“This is overly burdensome to us in the [emergency department] where most of our prescriptions are for a few days to treat acute symptoms,” Strang wrote.

Lukas Kolm, president of the New Hampshire Medical Society, warned that general practitioners would simply stop prescribing opioids rather than follow the “detailed and burdensome clinical, administrative, and documentation requirements.” He predicted that emergency rooms and urgent care centers would “overflow with patients in distress.” Those unable to obtain the medication from providers would resort to the black market.

Attorney General Joe Foster, whose office helped craft the draft revisions, says that, as it stands, New Hampshire has “no real rules.” The proposal before the board, he says, shares common ground with tougher guidelines already adopted in Vermont, Maine, Kentucky, Washington and other states.

“There is a lot of workload on doctors today, and I understand that,” Foster says. “But nobody is trying to prohibit anyone from having their pain treated.”

A growing demand for pain medication

A misconception about prescription drug abuse is that it’s most common in teens and young adults who poach the drugs from medicine chests or buy them on the street.

But, in February, researchers with Brandeis University’s Heller School for Social Policy and Management reported that, even as overdose deaths have soared, non-medical use of prescription painkillers has declined every year since 2002. Andrew Kolodny, a senior scientist at the Heller School and lead author of the study, says policymakers have for too long focused on “bad apples” when the biggest driver of deaths is the well-meaning prescriber.

“We don’t have two distinct groups - the so-called drug abusers who are harmed and millions of pain patients who are all helped,” says Kolodny, who is also the medical director for Phoenix House, a nonprofit that treats drug and alcohol dependency. “There is a tremendous overlap, and it’s the people with pain who have been disproportionately harmed by aggressive prescribing.”

By most standards, Chris Clough prescribed aggressively. Then again, it was his job to care for people with intractable pain, and for many of his patients, opioids seemed like the only treatment that worked.

Partly because of its aging population, New Hampshire has seen the demand for pain-related health care rise sharply in recent years. Over the last decade, by one calculation, the rate of nerve blocks, epidural steroid injections and other pain procedures grew faster in the Granite State than anywhere else. And, last year, the Centers for Disease Control reported that only Maine and Delaware prescribe more oxycodone and other long-acting opioids per-capita than New Hampshire.

Chris Clough joined the staff at PainCare Centers, a statewide chain of 10 office-based clinics and two ambulatory surgical centers, in 2004. Staffed largely by nurse anesthetists and physician assistants, PainCare treats hundreds of chronic pain patients each year, many of them poor or elderly.

Most of them are on prescription painkillers.

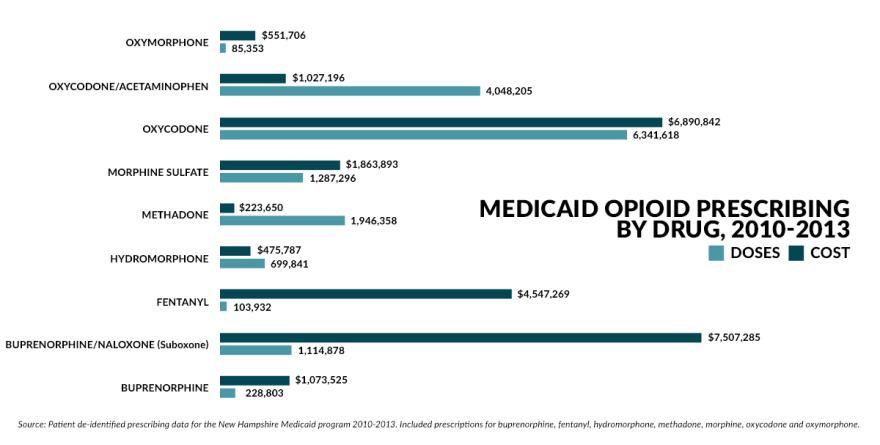

Eight of the 10 most prolific opioid prescribers in the state’s Medicaid program from 2010 through 2013 worked for PainCare, including Clough, who ranked third. Nearly one in seven painkiller prescriptions came from a PainCare provider, according to state prescribing data. PainCare accounted for about 3 million, or more than 20 percent, of the 14.5 million doses prescribed over the four-year period.

Michael O’Connell, PainCare’s founder and CEO, declined to be interviewed for this story. In a statement issued through his attorney, he said PainCare sees more Medicaid patients - a group he characterized as “clinically complicated” - than other pain practices. So it stands to reason his staff orders more opioids under the program, he said.

“In addition, many providers, even pain management providers, do not have the resources, the knowledge or the desire to handle the most complicated chronic pain cases,” he said. “These patients are often referred to PainCare already being prescribed high doses of opioids.”

Clough is one of about a half-dozen providers since 2010 who have been reprimanded for professional misconduct related to prescribing practices. According to the board’s disciplinary archive, most cases end with a settlement agreement and no public hearings.

Clough, however, hired an attorney and set out to fight the charges, which originated with a former colleague. In a lengthy complaint, Joshua Greenspan, a former PainCare medical director who now practices in Portsmouth, accused Clough of performing pain injections that weren’t medically necessary. After reviewing more than 125 patient charts, Greenspan said he determined that Clough’s poor clinical judgment and “lack of competence” had put patients at risk.

Gilbert Fanciullo, a professor of anesthesiology at Dartmouth’s Geisel School of Medicine and director of pain management at Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, was the board’s expert witness in the case. Fanciullo’s credentials include co-chairing a multidisciplinary panel commissioned by the American Pain Society to review the scientific evidence and produce clinical guidelines for the use of opioids for non-cancer pain.

He recalls that, when the group began their work in early 2006, there were significant gaps in the research. So little was known, Fanciullo says, “we believed that if you prescribed opioids to somebody with chronic pain, the risk of addiction was low.”

Good studies on the pros and cons of chronic opioid use were especially hard to come by. But the group nonetheless agreed on a detailed set of recommendations that was published in The Journal of Pain. The final document, which numerous states, including New Hampshire, adopted as a foundation for their own recommendations, urged caution at every step - from choosing and evaluating patients, to monitoring their compliance, to deciding when and how to wean them off the medication.

Despite the lack of data on dosing, the panel decided that patients taking 200 mgs or more of morphine equivalent a day - roughly 130 mgs of oxycodone - were “high-dose” and required extra vigilance, including more frequent follow-up visits.

Up to that point, Fanciullo says, “people genuinely believed there was no upper limit. The right dose is whatever people need - that was sort of a mantra for a lot of opioid prescribers.”

Including Chris Clough.

A last resort?

By his own account, Clough might be the highest paid physician assistant in New Hampshire. During his two days of testimony in April, he told the board he earned $200,000 to $250,000 a year, including a 30 percent commission on the revenue from services billed to Medicare, Medicaid and private insurers.

Indeed, in 2012, Clough took in more Medicare reimbursement - some $210,000 - than any PA in the state, according to the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare. He performed almost 900 procedures, conducted 1,650 patient visits and ordered 2,500 opioid prescriptions.

Meanwhile, many of Clough’s Medicaid patients were on high doses of opioids. State prescribing data show that half of the more than 325,000 painkillers he prescribed from 2010 to 2013 went to just 22 patients, who averaged nearly 300 mgs of morphine equivalent per day.

Clough testified that his training in pain management consisted of working alongside O’Connell for a year, learning interventional procedures, as well as two or three “cadaver classes” to further his injection skills. He learned opioid prescribing from O’Connell, too, but added, “I probably consulted with everyone at PainCare at one time or another.”

In an interview last spring, Clough defended his prescribing habits as “evolving.” He acknowledged the growing evidence that long-term opioid therapy is both ineffective and potentially harmful. But, he said, nearly all of his patients were sent to him by primary care doctors and other specialists who were no longer willing to treat their pain.

"I don’t want to give my patients pain medicine, but unfortunately they come to me far too late in the process,” he says. “Maybe they’ve had two or three back surgeries that didn’t work. So now what are they left to do?

“You can start reducing, but some resist,” he continued. “They are afraid and don’t want to go back to the way they were.”

Cloughsaid he began reducing his patients' daily dose well before his disciplinary proceeding began, with the goal of getting them down to 200 mgs of morphine equivalent or lower. At that point, he said, the patients are prescribed buprenorphine, a less potent pain reliever that doesn’t carry the same risk of addiction as oxycodone and methadone.

Clough seemed worn down by the hearings. At one point, he pointed out that no patients had come forward to complain about how he did his job. “I care about my patients and my patients know it,” he said. “I didn’t kill anybody. I didn’t injure anybody. I did the best I could for a very, very complex set of patients."

He saved his harshest criticism for Fanciullo. He characterized the Dartmouth professor’s view that opioids should rarely be prescribed for chronic pain as “an interesting concept” and suggested he was out of touch with the demands of the job.

“He’s up there in a teaching hospital, and that’s a lot easier than being out in a community,” Clough said. “When he decides he can’t help somebody, which is often the case I assume, he just discharges them back into the community. If we do that, people fail.”

But Fanciullo’s views are hardly novel, even within the comparatively small world of pain management specialists. For several years, he said, residents in Dartmouth-Hitchcock’s pain program have been taught to consider opioids as a last resort.

Fanciullo recounted a recent conversation with a cancer patient referred to him by a palliative medicine specialist. The patient, who was taking about 500 mgs of morphine equivalent a day, wanted Fanciullo to take over his medication management. Fanciullo said he would only consider it if the patient’s dosage was tapered by more than half.

“I explained to him that I didn’t believe his medicines were helping him at all,” he said, “that they were probably making his pain worse and that his risk of dying just because he’s on that high dose is probably two percent per year.”

Many states have already adopted the more conservative approach favored by Fanciullo. The strategy is two-fold: to encourage providers to consider alternatives to opioids, while also providing the clinical skills to prescribe them safely if they are needed.

About a dozen states now require clinicians who prescribe opioids to complete courses in pain management and controlled substances. New Hampshire’s proposed rule requiring mandatory drug testing at least once a year for chronic pain patients is the law in several states. Others have created a “threshold dose” that triggers stricter rules for monitoring patients. If adopted, New Hampshire’s rules would require providers to “consider” referral to a pain management specialist when the daily morphine equivalent reaches 100 mgs.

More than a half-dozen states have targeted clinics and physicians who write the most opioid prescriptions. Florida’s so-called "pill mill" law, along with expanded use of the state’s prescription drug monitoring program, is credited with a measurable drop in the amount of opioids dispensed by pharmacies.

Perhaps the state with the the most comprehensive guidelines is Washington, which was the first state to focus on physician behavior as a strategy to reduce opioid prescriptions. The initial guidelines were published in 2007 and included a “yellow flag” dose of a 120 mg daily morphine equivalent. The most recent update was released earlier this year and advises clinicians that the risk of overdose doubles at doses as low 20 mgs and increases nine-fold at 100 mgs or more.

David Tauben, chief of the University of Washington Division of Pain Medicine, says the guidelines have helped convince many physicians that chronic pain can be managed without opioids. But it didn’t come easy, he says. Physicians and patient advocates fought the changes, warning that chronic pain patients would suffer as physicians opted to stop prescribing opioids rather than adhere to the new rules. That never happened, Tauben says.

“I was on the fence about whether laws were the right way to go about this, but medicine has failed to regulate itself in the area of opioid prescribing,” Tauben says. “It’s a dismal failure of the profession. And when the profession fails, government takes action, and that’s what it has had to do.”

Given the backlash against the draft revisions, it’s unlikely the Board of Medicine will move as quickly as the governor would like. That might be one reason Hassan announced that she will propose a special legislative session to craft new substance-abuse legislation.

In a press release Tuesday, the governor said she will propose a draft bill that incorporates elements of the board’s draft revisions, including dosing limitations and a mandate to use the prescription drug monitoring program. The governor also wants $5 million for community-based treatment and prevention, $3 million to create a statewide drug court system and $100,000 to upgrade the drug monitoring program.

Attorney General Joe Foster says he knows physicians are lining up to oppose any proposal that might interfere with how they care for patients. But, he added, “I would hope the medical community takes hold of this and puts in place some thoughtful rules. The need is definitely there.”