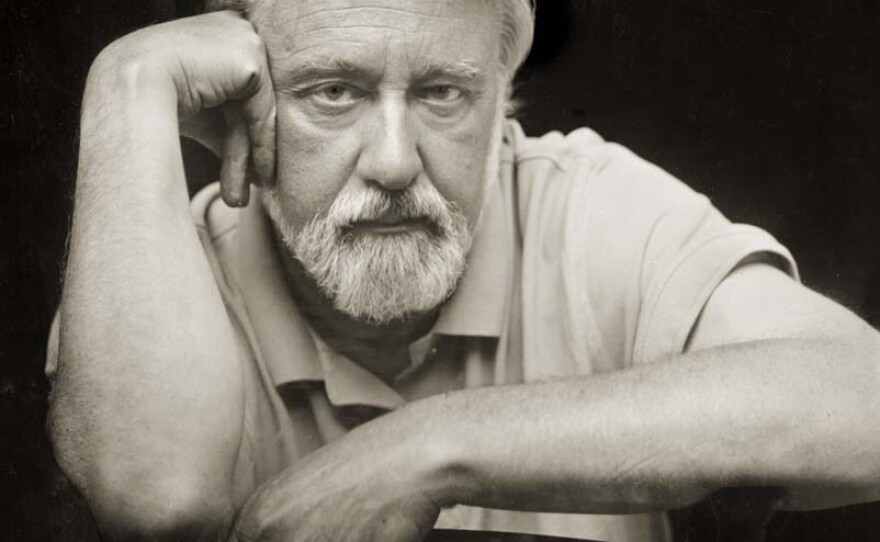

Last week, Concord-based photographer and filmmaker Gary Samson was named New Hampshire’s Artist Laureate. Samson built his career exploring the history and culture of the Granite State. He now serves as Chair of Photography at the New Hampshire Institute of Art. Samson reflected on his approach to photography with NHPR’s Peter Biello.

Tell us about this honor. What will it mean for you to be named the state’s artist laureate?

Well, I have always felt that one of the roles that I should play as an artist resident of the state for my life is to advocate for the arts, and now I have an official platform with this honor.

I’ve got some portraits here that you brought in, and I have to say they’re stunning. Just looking into the eyes of your subjects, people of all ages and genders, musicians. Are these folks in New Orleans?

Yes, the musicians are from New Orleans. It’s from a book that Burt Feintuch and I completed a year and a half ago, it’s called [Talking] New Orleans Music, and we spent three years interviewing subjects and photographing them for the book.

I was reading, Gary, that as you are setting up a camera for a portrait, you are talking to your subject and getting to know them a little bit, and in doing so you are getting a better sense of how the portrait should come out in your view. What kind of questions do you ask your subjects as you’re getting them ready for the portrait?

I really want the subject of the photograph to rule the frame. That’s actually a term that the great portrait photographer Lotte Jacobi used many years ago. So I try to be gentle with my subjects, and I think sometimes the subject takes me someplace I wouldn’t have otherwise gone. I try not to have a preconceived idea about how to portray them. I want them to give me that lead.

You’ve written that a summer job you once had at the Manchester Historic Association made quite an impression on you early in your career. Can you tell us about the impression it made?

It’s amazing what, you know, chance will do to someone’s life. I had been, as a teenager, hanging around the Manchester Historic Association. It was only four or five blocks from my house. I think it was a friend that brought me in one day, and I was starting to have a real interest in photography. I went upstairs to the library and I saw this incredible collection of photographs that documented the history of Manchester—you know, Manchester being one of the great Industrial Revolution cities, the Amoskeag mills pouring out miles of cloth every day. So the director of the museum said, you know, would you be interested in a summer job, and I said, absolutely.

I did everything from sweep the floors and polish the brass rail and wash windows to working in the library. The librarian allowed me to take some of the glass negatives and make prints in what they called a slot closet. I knew a little bit about black and white printing, handled the negatives very carefully, but I had the chance to go through literally thousands of photographs that documented the rise and fall of the Amoskeag mills, the people who worked there. These were all beautiful, for the most part contact prints, eight by ten-ish contact prints from negatives.

This was a story that, as a sixteen or seventeen-year-old boy that I—the pictures made it real. And I’ll go further by saying that—I’m a first generation American. My father and my grandmother actually came to Manchester from Quebec to work in the Amoskeag textile mills. So to learn about the history of the city and specifically the mills, and the many different ethnic groups, the French-Canadians they employed, this was very meaningful to me. I was learning in that moment how powerful photography could be as a tool of communication.

Tell us about your experience as a filmmaker.

I had the good fortune after I graduated from school, the University of New Hampshire offered me a job. And my job was to be the black and white dark room technician. I took other photographers’ negatives and I made prints, and I had that job for about nine months before I was promoted to being a staff photographer. I wanted to make a film about the history of the Amoskeag Manufacturing Company. I really didn’t know anything about filmmaking. I had taught myself a little bit as a twelve or thirteen year old working with an eight millimeter camera, so I made a first draft of the film, I showed it to people, and they said, we will give you the money to finish the film.

The film was half an hour long—I finished that film in January of 1976. It was premiered in Manchester at the Historical Association. The auditorium space that they had to show the film would seat, I believe, about forty five people. We had, I think, about seven hundred people show up for that film. It was late February, if memory is serving me correctly. What we did was people stood outside the museum in the cold for hours. We didn’t stop showing that film until almost 6 pm, 45 or 50 people at a time cycling through.

I knew that, taking these historical photographs, putting them together to tell the story of the rise and fall of the mills and the people who worked there, had really touched people’s hearts. Because, at the time, in the mid-seventies, people’s parents and grandparents had worked in the mills, and some of those people had worked in the mills, and it was a validation of their life.

Your work seems so much more than just creating a beautiful picture or beautiful film. What it seems like to me is that you’re very much driven by preservation, by wanting to preserve the stories of the people around you, of the people who mean a lot to you.

Yeah, going back to the Manchester Historical Association and their collection—I’m a teenager looking at photographs that were made a hundred years earlier, more than a hundred years earlier. And I think that whole idea that photographs could preserve culture over time, that I could look back and see the mills as they appeared in the 1870s and 1880s and the people who worked there—I saw photography as a kind of legacy, a way to preserve culture.

I hope that people will regard at least some of the work that I have created as important, and maybe someone a hundred and fifty years from now will look at my work and derive the same pleasure and knowledge that I did as a young teenager looking at these photographers.