Roger Boisjoly was a booster rocket engineer at NASA contractor Morton Thiokol in Utah in January, 1986, when he and four colleagues became embroiled in the fatal decision to launch the Space Shuttle Challenger.

Boisjoly was also one of two confidential sources quoted by NPR three weeks later in the first detailed report about the Challenger launch decision, and the stiff resistance by Boisjoly and other Thiokol engineers.

The experience both haunted and inspired Boisjoly in the decades that followed. We learned this weekend from this story in The New York Times that Boisjoly died last month in Utah at age 73.

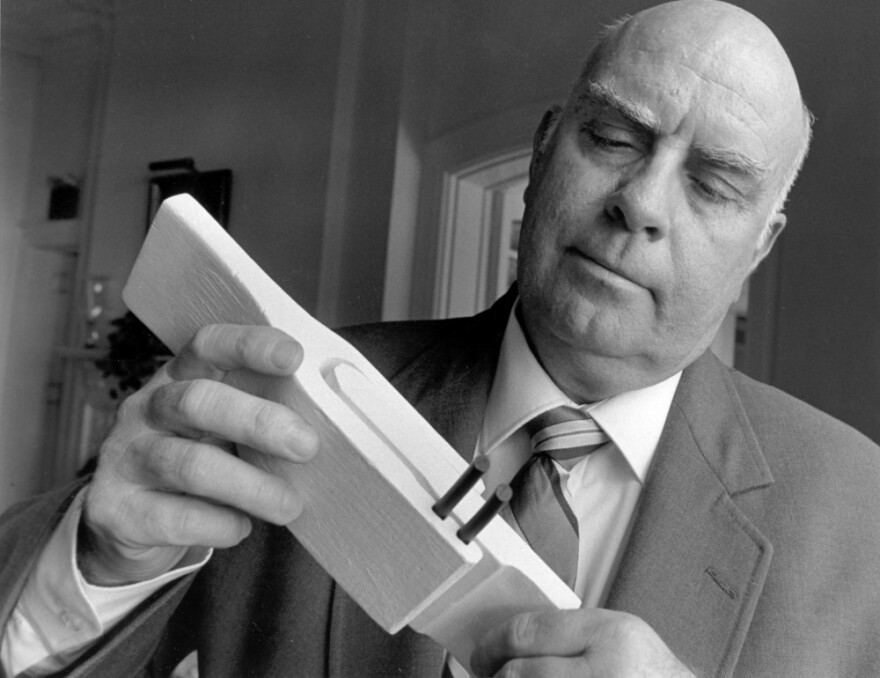

Bulky, bald and tall, Boisjoly was an imposing figure, especially when armed with data. He found disturbing the data he reviewed about the booster rockets that would lift Challenger into space. Six months before the Challenger explosion, he predicted "a catastrophe of the highest order" involving "loss of human life" in a memo to managers at Thiokol.

The problem, Boisjoly wrote, was the elastic seals at the joints of the multi-stage booster rockets. They tended to stiffen and unseal in cold weather and NASA's ambitious shuttle launch schedule included winter lift-offs with risky temperatures, even in Florida.

On January 27, 1986, the forecast for the next morning at the Kennedy Space Center included a launch-time temperature as low as 30 degrees Fahrenheit. NASA had never launched in temperatures that cold and Boisjoly and his four colleagues at Thiokol headquarters in Utah concluded it would be too dangerous too launch.

Three weeks later, he told NPR's Daniel Zwerdling in an unrecorded and confidential interview, "I fought like Hell to stop that launch. I'm so torn up inside I can hardly talk about it, even now."

But Boisjoly did talk about it in a hotel room in Alabama, revealing for the first time the details of that effort to keep Challenger on the launch pad. He asked that he not be named but he agreed to be quoted anonymously. As he spoke with Zwerdling, a second engineer revealed the same details to me under the same conditions at his home in Brigham City, Utah.

Boisjoly's family agreed to release him from our pledge of confidentiality so that his efforts to get the truth out can be widely known.

"We all knew what the implication was without actually coming out and saying it," a tearful Boisjoly told Zwerdling in 1986. "We all knew if the seals failed the shuttle would blow up."

Armed with the data that described that possibility, Boisjoly and his colleagues argued persistently and vigorously for hours. At first, Thiokol managers agreed with them and formally recommended a launch delay. But NASA officials on a conference call challenged that recommendation.

"I am appalled," said NASA's George Hardy, according to Boisjoly and our other source in the room. "I am appalled by your recommendation."

Another shuttle program manager, Lawrence Mulloy, didn't hide his disdain. "My God, Thiokol," he said. "When do you want me to launch — next April?"

These words and this debate were not known publicly until our interviews with Boisjoly and his colleague. They told us that the NASA pressure caused Thiokol managers to "put their management hats on," as one source told us. They overruled Boisjoly and the other engineers and told NASA to go ahead and launch.

"We thought that if the seals failed the shuttle would never get off the launch pad," Boisjoly told Zwerdling. So, when Challenger lifted off without incident, he and the others watching television screens at Thiokol's Utah plant were relieved.

"And when we were one minute into the launch a friend turned to me and said, 'Oh God. We made it. We made it!'" Boisjoly continued. "Then, a few seconds later, the shuttle blew up. And we all knew exactly what happened."

Until NPR's story, the special commission investigating the Challenger tragedy hadn't even interviewed all the engineers involved in the pre-launch debate.

The explosion of Challenger and the deaths of its crew, including Teacher-in Space Christa McAuliffe, traumatized the nation and left Boisjoly disabled by severe headaches, steeped in depression and unable to sleep. When I visited him at his Utah home in April of 1987, he was thin, tearful and tense. He huddled in the corner of a couch, his arms tightly folded on his chest. But he was ready to speak publicly.

"I'm very angry that nobody listened," Boisjoly told me. And he asked himself, he said, if he could have done anything different. But then a flash of certainty returned.

"We were talking to the right people," he said. "We were talking to the people who had the power to stop that launch."

Boisjoly testified before the Challenger Commission and filed unsuccessful lawsuits against Thiokol and NASA. He continued to suffer and was ostracized by some of his colleagues. One said he'd drop his kids on Boisjoly's doorstep if they all lost their jobs, according to his wife Roberta.

"He took it very hard," she recalls. "He had always been held in such high esteem and it hurt so bad when they wouldn't listen to him."

A therapist recommended speaking out even more and for close to three decades, Boisjoly traveled to engineering schools around the world, speaking about ethical decision-making and sticking with data. "This is what I was meant to do," he told Roberta, "to have impact on young people's lives."

Boisjoly continued to respond to emails and letters from engineering students right up until his sudden death in his sleep last month in St. George, Utah. He was diagnosed with cancer two weeks before.

"He always stood by his work," Roberta recalls, her voice breaking. "He lived an honorable and ethical life. And he was at peace when he died."

Copyright 2021 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.