Like many a millennial hired at the dawn of the era of social media, Zachary Byam found himself in charge of creating a Facebook page at his college job.

But his task was unique. Byam worked as a part-time police officer, and he was creating his department's first social media account.

Byam, now 27, was a relatively early adopter of Facebook. He grew up in Harrisville, New Hampshire and guesses that he joined in 2007 or 2008, "probably just after or right around high school."

After he graduated from college, Byam brought his social media experience to his new job at the Marlborough Police Department, just minutes from his hometown.

"It was actually a pretty good success for us over there and when I came over here, I floated the idea for our department to get one too," Byam said.

Local police department Twitter and Facebook accounts often function as a public service, posting road closings, weather warnings, community notices, and other information.

But not so the Marlborough Police Department.

"I think it's just a relief from the, I guess, boring... I won't name any names, but there's plenty of police departments that have Facebooks but they're your standard, run-of-the-mill, stuff you'd find on their website, type of thing," said Byam.

The department’s feed is peppered with tongue-in-cheek posts about rules of the road, often in the style of classic memes that Byam makes himself.

"There's one with the Barney Stinson meme from How I Met Your Mother, and it just says 'eyes on the road, not the phone,'" Byam said.

In 2017 Byam attended an in-service training called Social Media for Modern Policing organized by the New Hampshire Police Standards & Training with Granite State Police Career Counseling.

Byam has had some success with the page. In a town with a population of just over 2000 people, he’s got 6000 followers – not bad for a police department with just three full-time staff.

He's not alone in his efforts to maintain a funny presence on the police Facebook. For instance, Portsmouth Police Department adopts a humorous tone on Facebook and Twitter, and the Bangor Maine Police Facebook is famous, in relative terms, for its long-term success.

While some commenters don’t like seeing police time spent Facebooking, Byam says he’s often actually off-duty when he writes his posts. Plus, his fans leave comments in the spirit of “keep it up!” or “love a cop with a sense of humor."

Every once in a while, someone asks: when are you going to enter the lip sync challenge?

They’re asking Byam to jump into a trend among police departments across the country in which departments film officers lip-syncing to pop songs and performing choreographed flash-mob-style dance routines, all in full uniform.

Perhaps the most famous is an elaborate rendition of Bruno Mars' "Uptown Funk" performed by Norfolk, Virginia’s police department. It has 78 million views on facebook and counting.

A handful of New Hampshire police departments have also entered the fray, including Hudson, Hooksett, Concord, and Londonderry, whose video includes a cameo by Governor Sununu.

But lip sync videos are not the only type of video involving police officers to go viral in the past few years. Law enforcement institutions are under national scrunity after a series of high profile examples of police brutality, often recorded on bystanders' cell phones or dash cams. Calls for criminal justice reform also focus on systemic racial profiling, unconstitutional policies like stop-and-frisk, and mass incarceration.

A lot of that scrutiny started on Twitter, the platform where Black Lives Matter began.

As police departments enter that space, some agencies, like the Marlborough Police Department, choose to use social media platforms in attempt to engage with their communities.

But who are they reaching, and what is the message? Does humor help, or does it miss the point?

Trust and police legitimacy

"The million dollar question is: who actually is watching these things?" said Justin Nix, an assistant professor at the school of criminology and criminal justice at the University of Nebraska in Omaha. He studies police legitimacy, police-community relations, and officer-involved shootings.

'Setting aside what the reasons are that trust has been diminished, and whether we agree or disagree over whether a shooting was justified or not, we have to acknowledge that there has been a legitimacy crisis in last few years.'

"If it’s people who already have positive views of the police, then there’s probably not a lot of room for improvement. If it’s the people who have less positive views toward the police that are watching them, it's still a question of does the video work the way they want it to?"

Nix says he doesn't have the answers, and he's not aware of academic research that has considered those questions.

"Setting aside what the reasons are that trust has been diminished, and whether we agree or disagree over whether a shooting was justified or not, we have to acknowledge that there has been a legitimacy crisis in the last few years."

In an effort to find ways to restore public trust, the Department of Justice created the Task Force on 21st Century Policing to study possible solutions. The task force’s final report, published in 2015, laid out a series of recommendations organized into six pillars, including technology and social media.

The report encourages agencies to adopt policies that treat social media as “a means of community interaction and relationship building, which can result in stronger law enforcement.”

Does that include humor?

Making light of marijuana

In Marlborough, New Hampshire, Sergeant Byam hasn’t waded into the lip sync battle. He says he’s focused on using humor as a tool to get more exposure and get information to his community.

"When we're looking for a wanted person... I posted one, a classic 'looking for so-and-so, please call us if you know where he is.' And it was pretty much unsuccessful because it really didn't get any attention on it," said Byam.

But when he used humor, he watched the shares and likes go "through the roof." The message was: humor works. If you want to be seen online, be funny.

That principle brought Byam's page into the limelight in late August 2018. It started with a phone call from a deer hunter who, while out scouting in a remote spot on the southern side of town, spotted an illegal marijuana grow.

"[Marijuana is] decriminalized in New Hampshire now. You’re still not allowed to possess it but they’re not handing out the more strict penalties anymore. The growing is more of an issue," said Byam.

Rather than trying to catch the grower, the department chose instead to confiscate the weed. It took a few officers less than an hour.

"As part of that, I kind of got the idea that we could be a little clever and actually left a sign on a post at the site of the grow," said Byam.

Byam typed up a sign reading, “Sorry about your luck. Plants may be claimed in person, at the Marlborough Police Department. Please bring your photo ID.”

Byam had it laminated and attached to a stake, and then stuck it in the ground where they’d dug up the plants. In the parlance of the internet, you might say he was trolling the growers.

He posted a picture of the sign plus a few images of the plants, leaning against a cop car, their roots bagged in black plastic, paired with a caption:

FACT: Possessing small amounts of marijuana has been decriminalized in NH.

FACT: This doesn't mean you can grow 25 marijuana plants on someone else's property.

FACT: Using your fine-tuned horticultural skills to grow delicious organic tomatoes is much more rewarding and much more legal.

#WeedWhackerWednesday

"It was a good way to tell the community that, yes, this did occur. You know, if you are growing marijuana in Marlborough, we’re not gonna look the other way about it. If someone reports it to us, we have to do what we have to do but we're also not going to make a federal case out of it," said Byam.

For Byam, the post was a joke, but also a way to be transparent about the department’s decision. The post got over 700 shares, 200 comments, and it made local news, plus The Boston Globe.

"It obviously blew up quite big because I think it's a little outside the norm for that to be posted on a police department facebook page," said Byam.

So, Byam had a little fun with the situation. What’s wrong with that?

"Well, I really think the intent is worthy. I don't think anyone is out there to belittle anyone," said Chris Burbank, retired Salt Lake City police chief.

He’s also Vice President of the Center for Policing Equity (CPE), a nonprofit think tank focusing on racial profiling, use of force, and immigration issues.

Burbank doesn't condemn police efforts to be friendly and lighthearted on social media.

"They're trying to interact and engage with the public in a way that shows police officers different than when we’re issuing you a speeding ticket or taking you to jail or interjecting ourselves into someone’s life because of a horrible situation," he said.

"The challenge that police officers face is even when you arrive in a situation and in essence prevent something from happening, that event can be so traumatic that that might be the worst thing that's ever happened to them... even though from a policing standpoint, that’s a good thing."

Burbank sees humor in Byam's weed post. "But the challenge that you get is: look at all the people that have been incarcerated because of marijuana, and look at all the people of color who have been incarcerated inappropriately for misdemeanor, marijuana."

"This has been [a] tremendous impact on society and that has been, what many would argue, as would I, a tool of oppression for poverty and people of color. And, so, absolutely that can be interpreted differently. "

This kind of racial disparity exists throughout the criminal justice system, not only for marijuana charges. And New Hampshire is no exception.

The state's population is 93% white, but as NHPR reported in 2016, in New Hampshire black people are 5.2 times more likely to be jailed than white people.

In Cheshire County, comparing 2010 census to records provided by the Cheshire County Department of Corrections on the jail population from 2015-2017, black people are four times more likely to be held in the county jail than white people -- slightly below the statewide rate.

Even posts that might seem innocuous, like memes about speed limits, are open to differing interpretations.

"I'm very fortunate," Burbank said. "And when I drive down the street, I get a speeding ticket, I'm upset, but pay the fine. If you are struggling to make it, that $160, $200 fine... you may choose not to pay it. It may be the difference between you feeding kids or paying the rent. And then are you going to end up in jail for that? And so to make light of anything that police officers do, is... I’ll say, less than professional in my mind. "

?

Social media strategy for police

Police departments cannot realistically choose not to be online. Social media is a part of life, and can be treacherous for anyone. The New Hampshire Standards and Training and the Granite State Police Career Counseling do offer training, like the class Byam attended last year, and the national conversaton is growing.

Lauri Stevens is a social media consultant for law enforcement and organizes the SMILE conference (Social Media and Internet for Law Enforcement), which will be held for the 16th time next spring. The conference includes seminars on communications and PR, investigation and legal issues, and review of how departments handled major incidents, like a hurricane or mass shooting.

Stevens actually spent part of her career as journalist.

"I covered a whole lot of emergencies with firefighters and police officers and other first responders," said Stevens. "And I just always could see that they didn't always get coverage they wished they could get from traditional media."

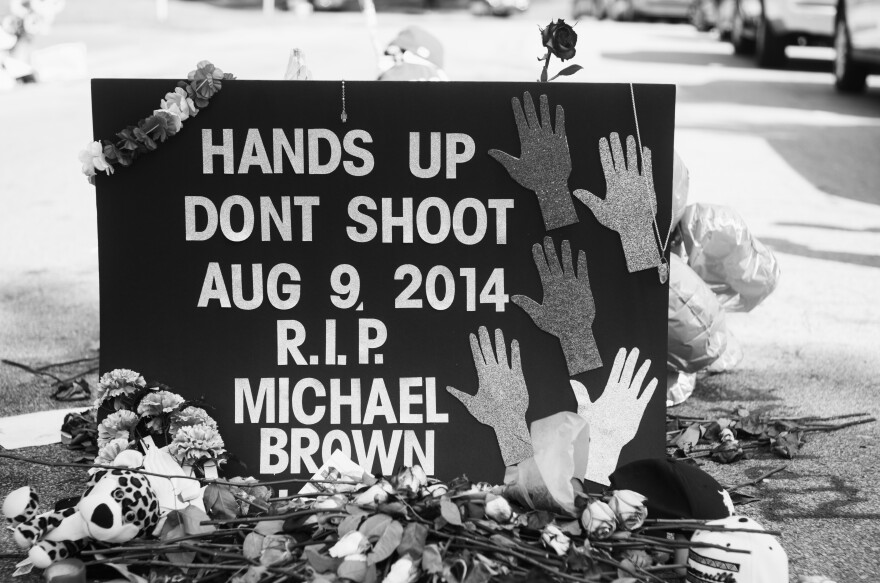

Stevens says that while some departments were early adopters of social media, others were more resistant. But events like Officer Darren Wilson’s fatal shooting of 18-year-old Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri sent a wake-up call.

"That was the whole start of the Black Lives Matter movement, 'hands up don't shoot.' And then we find out ten months months later, the 'hands up, don't shoot' never happened. It was just made up in social media," said Stevens.

Witnesses said that before Wilson shot him, Brown had surrendered with his hands in the air. "Hands up, don't shoot" became a rallying cry: a symbol of why police needed to be held to account. But after the protests, the Department of Justice investigation found there was not evidence to support that narrative that Michael Brown had his hands up when he died.

For those who took issue with the Black Lives Matter movement, this detail could be seen as validation for another narrative: that the police did nothing wrong.

But the “hands up, don’t shoot” debate misses a bigger takeaway from the 2015 Department of Justice investigation of the Ferguson Police Department, which found systemic violations against African Americans in “nearly every aspect of Ferguson’s law enforcement system.”

Protesters of police misconduct did not go away, and the focus on the “hands up, don't shoot” story misses the point. And meanwhile, Black Lives Matter, a movement born on Twitter, resonated with people across the country.

"And it just took off and it took control away from the police," said Stevens. "Even though in tiny Ferguson, Missouri, maybe they were thinking that we really don't need this stuff, it doesn’t matter how small you are."

"You need to be out there using it before you really need it, building relationships and earning the trust of the community that you serve so that when you need them and when you need to be getting out messages to try to control the story... and I always hesitate to use that word, 'control'... really, steer the story, rather. You can't do that if you're not out there already using it."

But if the Department of Justice recommends using social media as a tool for building relationships, access, and trust, can law enforcement agencies also use it to control or steer the story? Or are those goals at odds?

There are legal issues when it comes to police social media accounts, including policies around on and off duty use, freedom of speech, or whether a Facebook page counts as a public forum or not. Stevens encourages agencies to adopt a clear policy.

Her policy tries to address some of those legal questions. But what about humor?

"Humor is a good thing. It can really soften that relationship between a police department and its audience. But you've got to make sure you’re funny first. You don't want to overdo it," said Stevens.

"But the other thing is that what flies in one town isn't necessarily going to work even in the very next town and so I never stand before my students and say, 'don't do this ever, or do this always.' It really has to be decided in-house."

Missed Connections

In Marlborough, the person who decides what’s funny on the police facebook is pretty much Sergeant Byam. He has fans both in his community and beyond, but some think it's inappropriate for police to use humor.

"I think there are very few... obviously it doesn’t change what we do because there’s always going to be people against what you do in general," said Byam.

"There are a few people who I think are kind of stuck in the old way. They like their police to let them know if there's some sort of major incident, but otherwise do their jobs and be quiet about it. I think those people sometimes take issue with the positive attention that we get."

A lot of the criticism of Byam's marijuana post were written by commenters who thought weed should be legal – so why are police spending time confiscating plants? Again, Byam says the police don’t get to decide which laws they enforce or not, and anyway, the department opted to take the lesser action of seizing the plants rather than pursuing the grower.

But Byam says he doesn’t moderate those comments (beyond profanity and threats to incite violence) and that he wants the Facebook page to be a two-way dialogue.

"Every once in a while when people are getting a little overboard... I do like to respond in lighthearted way. Sometimes it defuses people a little bit to see that we're not the big bad guy that they have painted in their minds," said Byam.

Byam says that he tries to be tasteful in where he uses humor, and that he avoids jokes in cases like an accident or an arrest.

"It's not tasteful probably to try to make light of something that people might be suffering through," said Byam.

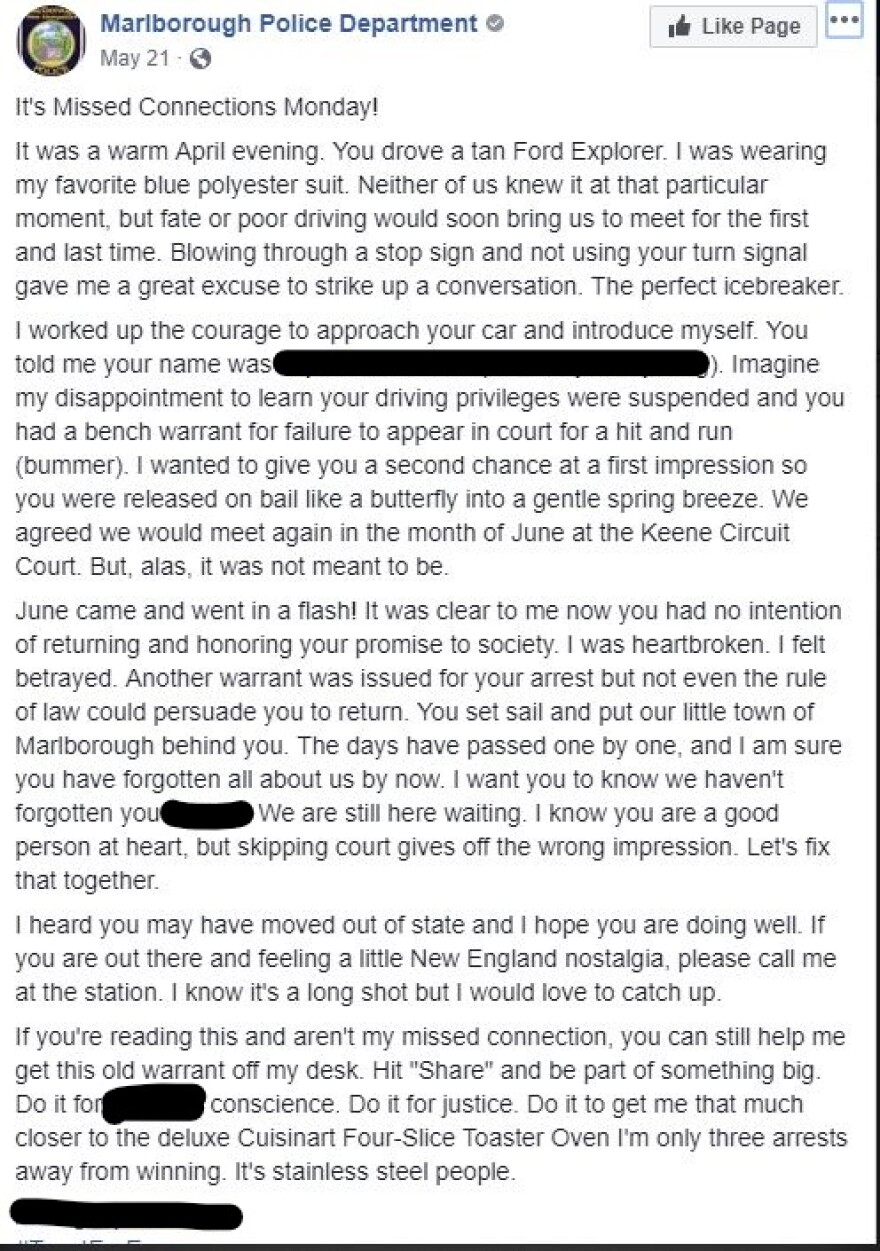

But this isn't always consistent. For instance, Byam sometimes posts "Wanted" notices which include photographs of people who don’t turn up to court. When one woman didn't show up for her court date in May 2018, Byam wrote his most popular post to date. He assumed the style of a Craigslist Missed Connections ad, with a suggestion of romance.

It was a warm April Evening. You drove a tan Ford Explorer. I was wearing my favorite blue polyester suit. Neither of us knew it at that particular moment, but fate or poor driving would soon bring us to meet for the first and last time. Blowing through a stop sign and not using your turn signal gave me a great excuse to strike up a conversation. The perfect icebreaker...

If you’re reading this and aren’t my missed connection, you can still help me get this old warrant off my desk. Hit ‘share’ and be part of something big... Do it to get me that much closer to the deluxe Cuisinart Four-Slice toaster oven I’m only three arrests away from winning. It’s stainless steel people.

Byam's post was shared over ten thousand times, photograph included. It also made local headlines. The Keene Sentinel quoted Alex Parsons, the managing attorney of the New Hampshire Public Defender's Keene office, responding to this post, who wrote, “To be made the brunt of a public joke by an authority figure is unlikely to engender respect in anyone.”

Some police departments regularly do post mug shots on their twitter, but others never do, like Lieutenant Tim Cotton, manager of the Bangor Maine Police Facebook. The page has over 300,000 followers and is known for its gentle humor and taxidermied duck mascot, dubbed the Duck of Justice.

In a phone conversation, Lieutenant Cotton said he made the decision a long time ago that he wouldn’t post mug shots on the Bangor page.

While an arrest log and mug shot is public information, on social media, the difference is the degree of amplification.

"It wanders into that realm of some sexist behavior," said Burbank, referring to Byam's Missed Connections post. Plus, he pointed out that the entire situation highlights more systemic problems of inordinately punishing poverty through repeated jail time and accrual of fines.

"We issue a benchwarmer, we take them to jail, we issue a benchwarmer... so by the time somebody in poverty actually sees a judge, that fine has now gone from $50 to $1050 and they have no chance of paying it, so then they spend some time in jail," said Burbank.

"We have perpetuated a system where if you get caught up in it, you don't recover. We have to be aware of that."

To serve, to protect... to entertain?

Just down the road from the Marlborough Police Department, in the same county, lies the Cheshire County Department of Corrections, or the county jail. It’s hidden from the road by a huge earth bank, and as you pull around and up the hill, there’s no barbed wire in sight.

Jail superintendent Richard Van Wickler is a vocal critic of the criminal justice system, especially the war on drugs. He’s former chair of the board of the Law Enforcement Action Partnership and has testified at the State House in support of marijuana legalization. He's been interviewed by local papers, in a documentary on incarceration, and for a profile on Vice.

Now, as Van Wickler’s gives a tour of the jail, it’s clear to me that he’s pretty media savvy. As we’re walking, he invites me to take pictures and makes sure to introduce me to everyone we pass in the hall by full name and title.

Because of the county jail system in New Hampshire, Van Wickler has a lot of control over the training and philosophy of his operation. Van Wickler says that every part of the jail, which he designed with his staff, deviates from traditional corrections and instead reflects "modern inmate behavior management." It leans on academic research and involves deescalation techniques and a system of incentives and disincentives for good behavior.

"My personal view is that it is not law enforcement's responsibility to entertain the public. Our responsibility is to protect the public," said Van Wickler.

"What I’ve learned in law enforcement of 32 years is that everybody has a different frame of reference. The inmates have a different frame of reference than we do. My correctional staff has a different frame of reference than I do. And then the family of the inmates have a different frame of reference."

Van Wickler says members of law enforcement are in a position of responsibility, and although a joke might make a particular audience laugh, it's inappropriate.

"Sarcasm can backfire, and sarcasm has no place in the administration of justice in my view."

"The people that think it’s funny are probably people who have not had any negative interaction with law enforcement. People that don’t think it’s funny might be somebody whose son or daughter was just arrested, or their mother was just arrested."

Van Wickler says this creates a divide in a community, and referred to the police legimitacy crisis.

"It also retrogrades the level of respect that we should have for our law enforcement. And I can tell you in my career that respect for law enforcement has diminished significantly."

Donuts are not politically neutral

Could a joke from a police department exacerbate the divide in a community? What happens when a lip sync video gets attention for the wrong reasons?

In July 2018, the Crandall Texas police department published a video in which officers lip sync to the song “God’s Not Dead," singing on a front porch beneath a sign reading “For God’s Glory."

In one scene, a uniformed officer leans over what appears to be a Bible in the dispatch center. The video drew criticism from some who felt it is inappropriate for a police department to endorse Christian words and ideas.

In York City, Pennsylvania, the police lip sync video depicted officers satirically investigating the murder of several jelly donuts. The crime involved Maple Donuts, a controversial business which sells a donut named for President Trump, and whose owner posted controversial billboards like “Maple Donuts Takes A Stand Not a Knee," in reference to NFL players kneeling during the national anthem in protest of police brutality.

In York City, Pennsylvania, donuts are not neutral. If the police hoped to connect to the community, the lip sync video had the opposite effect.

But even lip sync videos that don’t tread on controversy can be seen as, at heart, a PR stunt in poor taste.

When The New York Times published an article on the lip sync video trend in July, on Facebook, comments ranged from the positive to the critical.

"Pointless and clueless. How about an effort to fix the broken police culture?" wrote Gary Rosenbaum.

"I mean, I'd rather see video of them practicing de-escalation techniques or working on their implicit bias. But maybe that's just me," Leslie Sadowski-Fugitt wrote.

Humanizing the police force

"It's so complex," said Lauri Stevens, social media consultant for law enforcement.

"To just point the fingers at police really isn't fair. They're just trying to get bad guys off the streets..."

"To ask them to be major social workers and understand complexities... when they just want to make sure they’re going home at the end of the day is asking a hell of a lot, when you think about it."

"I just hate the finger pointing. I just hate this whole Black Lives Matter – of course they matter. Everybody's lives matter. That's really, really not the problem."

Is it too much to ask police officers to think like a social worker?

"This isn’t the kind of thing where you apply, get a job, and punch in and punch out," said Van Wickler, superintendent of Cheshire County Department of Corrections.

"It’s a discipline. It’s academic. It’s one that requires continual daily growth. And when you can’t grow anymore, when you can’t know anymore, you need to leave."

Burbank, vice president of the CPE, says if police want to be perceived differently, they need to do business differently.

"Collectively, across the nation, we are engaged in similar policing that produces similar outcomes. Who is incarcerated in this country? Who is held accountable?" he said.

"There is an unfair system in place and more people of color are held accountable, or held more severely accountable, for the exact same behavior. I don't care where you are in the country, that's the case."

Burbank wants police officers to be viewed as human beings.

"We have human frailties. We have emotion, we have sadness, we have happy times, we have drug and alcohol addictions, just like everybody else. We are human beings. We're a microcosm of society."

"But what we ask you to do as police officers, is to rise above all that and be that much more sensitive, caring, and empathetic, and understanding. And sometimes humor crosses that line."

The best part of policing, Burbank says, is the human. But a real change will require a lot more than lip synching.