As Scott Brown crisscrosses New Hampshire on what his senate exploratory committee is calling a listening tour, he’s repeatedly said it’s “premature” to talk about how he’ll wage any future campaign to unseat Democratic Sen. Jeanne Shaheen.

On one point, though, Brown has already been crystal clear: He doesn’t want this race to be bound by a so-called people’s pledge, an idea Brown himself devised in 2012 to limit spending by outside groups during his race against Elizabeth Warren.

When Shaheen proposed a similar arrangement last week, Brown called the offer “self-serving and hypocritical.”

He was more direct, according to the Concord Monitor, Wednesday night: “I have no intention of signing,” Brown said.

Money Already Flowing

As Brown has pointed out, outside groups began investing in the New Hampshire race months ago.

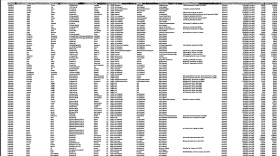

Americans for Prosperity launched a $750,000 ad campaign calling out Shaheen for supporting the Affordable Care Act. Another conservative group, American Crossroads announced a $600,000 ad buy last week with the same message. The League of Conservation Voters spent $220,000 on an anti-Brown ad campaign that accused the former senator of cozying up to oil companies.

All three are 501(c)4s – so-called dark money groups that are not required to disclose their donors.

Six weeks ago, at Cornell University, Brown talked about how outside spending can influence the political process, and not in a good way. In a video clip circulated Wednesday by New Hampshire Democrats, Brown took credit for the people's pledge, which he described as a “very unique way” to cut down on negative campaign ads.

"We didn't need another 30 to 40 million dollars coming in to distort our records and positions on things,” he said at the Feb. 6 event, billed as “Senator Scott Brown: Beyond Labels, the Problem with Partisanship.” “So what we came up with was the people's pledge.”

The People’s Pledge, v. 1.0

And it worked: Outside spending accounted for just over $8 million in the race, about 9 percent of the total spent, according to an analysis by Common Cause Massachusetts. A heavily contested Senate race in Virginia that year attracted more than $52 million, or 62 percent of the total, from independent groups.

The influence of dark money groups was also blunted by the pledge: Just 4 percent of the outside spending in Massachusetts in 2012 came from groups that do not disclose their donors. Nationally, 40 percent - some $400 million - of the more than $1 billion spent in federal elections in 2012 came from dark money groups.

Before Brown and Warren agreed to the pledge, outside spending had reached more than $3 million in the 2012 race, nearly all of it on television ads funded by two dark money groups, Americans Crossroads and the League of Conservation Voters.

Both groups would remain involved, especially in the final weeks of the campaign.

American Crossroads spent $637,000 on its robocall campaign against Warren in the last month alone. The America 360 Committee, a super PAC funded by Oxbow Carbon LLC, an energy company owned by William Koch, spent nearly $900,000 on direct mail to help Brown. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce spent another $400,000 on mailers.

On the Democrat's side, outside groups spent $3 million in the last month. The League of Conservation Voters dropped $1.1 million on mail and voter mobilization, more than half of that in the final four weeks. Labor unions and their affiliates spent more than $1 million late in the campaign, mostly on get-out-the-vote efforts.

“I don’t think it made a difference," Ray La Raja, associate professor of political science at the University of Massachusetts, said of the pledge, "and I think they knew that going in."

Both campaigns already had plenty of money. As Brown noted at Cornell, the two campaigns waged one of the most expensive Senate races in history, spending more than $77 million between them.

“I raised $42 million,” Brown said. “I think Sen. Warren raised $48 million, so we had plenty of money. A state like Massachusetts, 6.4 million people? C’mon.”

New Landscape

In a state like New Hampshire, 1.5 million people, spending like that to get elected would be unprecedented, if not inconceivable.

In the 2008 Senate race, Shaheen and her opponent, John H. Sununu, together spent $17.1 million. Two years later, Sen. Kelly Ayotte and Paul Hodes spent less than $8.5 million combined.

Both of those campaigns were before the onslaught of outside money – especially dark money - triggered by the U.S. Supreme Court’s Citizen’s United decision, which struck down limits on political spending by groups that operate independently of campaigns and the parties.

In the post-Citizen’s United era, the new standard in New Hampshire is the 2012 governor's race, when outside groups spent more than $19 million, or 82 percent of the almost $23 million spent.

It could have been worse: Neither Americans for Prosperity nor American Crossroads stepped up for the Republican candidate, Ovide Lamontagne, who had to largely make due with funding from the Republican Governor’s Association.

Meanwhile, in addition to $7.9 million from the Democratic Governor’s Association, Gov. Maggie Hassen enjoyed the generous support of labor and women’s groups that will likely get involved in a Shaheen-Brown race.

“It’s a good microcosm of the Democratic Party, post-Citizen’s,” said UNH political science professor Dante Scala of a Shaheen-Brown matchup. “Despite all the complaining about the Koch brothers, etcetera, the Democrats and their allies have done a good job of exploiting the advantages in this new campaign finance landscape.”

Brown’s Granite Status

Brown certainly has more to lose by turning down outside help this time around.

In 2012, he was a deep-pocketed incumbent. He’s in the opposite position this year: late getting in, against a sitting senator who is reasonably popular -and who ended 2013 with $3.4 million in the bank, according to the Center for Responsive Politics.

While no one doubts Brown's fundraising abilities, he's got some catching up to do. His Massachusetts-based political action committee, Fiscal Responsibility PAC, aka The People’s Seat, had $153,888 cash on hand at the end of 2013.

Brown also can’t count on the enthusiasm generated by a presidential election. Midterm elections swing on turning out the most committed voters, La Raja said, and outside groups have an outsized role in getting those voters to the polls.

“You want to activate your base in these types of elections, those are the people who show up,” he said. “He’s going to focus like a laser on Obamacare – he needs to get that message out, so there are going to be tons of ads on that.”

La Raja said Brown also can’t necessarily count on support from the Republican National Senatorial Committee.

“I think the national party is saying, ‘Listen, we have races in Kentucky, Louisiana, all these other places, and those races we think we have a better shot,” he said. “That’s my speculation, that they’re saying, ‘Just go for the outside money - we don’t want to waste money on you. It’s going to be a good race, but we have others that are more important.’”

As Shaheen continues to pressure Brown to agree to the pledge, recent polls on the race put her up by 8-10 points.

Given his status as an underdog, Scala said, Brown can’t afford to turn away any source of funding. Republican donor groups will likely step up and try to force Democrats to keep pace, he said. But whether that pattern continues is up to Brown.

“I imagine GOP super PACs will spend early, see what happens to Shaheen's numbers and get the Democrats to spend money in New Hampshire they would rather spend elsewhere,” Scala said.

“I doubt the outside money will be there for Brown in the endgame if he doesn't manage to close within striking distance.”