Summertime ushers in a bevy of fresh fruit enjoy and in no time, a bevy of fruit flies. With a keen sense of smell, fruit flies hone in on a juicy cantaloupe or overripe bananas tossed on the compost pile. Although they're a pest in the kitchen, fruit flies have been a focus of research for over 100 years, and today there are hundreds of labs dedicated exclusively to studying them.

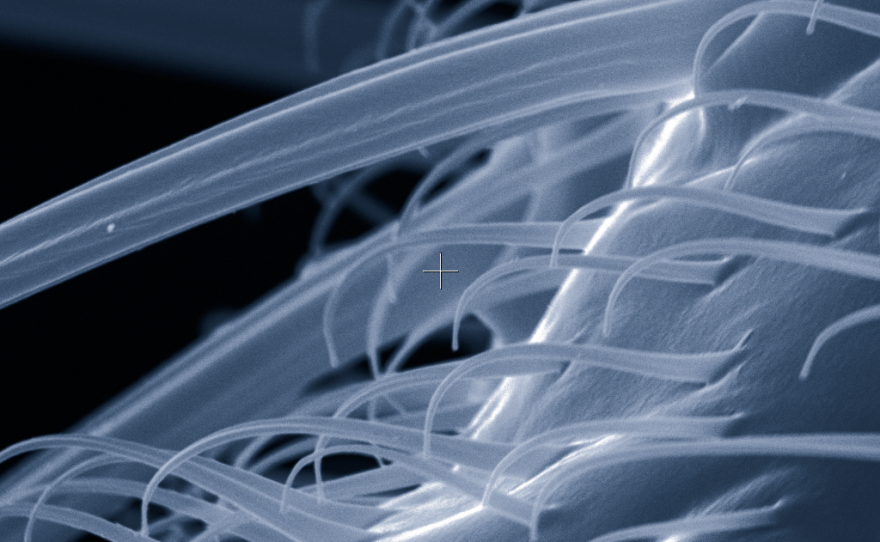

Compared to other lab species, the flies don't take up much space, they're easy to maintain and ethical treatment of the tiny bugs has not been an issue. Perhaps most important, generations come quickly, one every twelve days or so. Genetic experiments yield quick results as researchers analyze the DNA mutations of fly offspring. Give them a quick shot of carbon dioxide to calm them down and under the microscope they go.

In studies of memory formation, conditioning trains fruit flies to go towards one odor and not another. They can even be taught to gravitate to odors not associated with fruit, for example preferring smelly socks over ripe peaches. Related research has discovered a gene shared by humans and fruit flies that governs decision making. Mutations in that one gene can cause an inability to decide between two odors.

Current fruit fly research is focusing on two diseases of great concern to people: Alzheimer's and diabetes. Other research examines mechanisms that govern sleep, and how sleep quality impacts learning. We continue to learn a lot about ourselves from studying fruit flies in the lab. As for the wild fruit flies in your kitchen, some respect is due--before you banish them outside or suck them up in your vacuum.