While you’re binging on new episodes of Orange is The New Black this week, here in New Hampshire, architects are working with the Department of Corrections to design a real $38 million state prison for women.

And unlike most women’s prisons around the country, this 224-bed prison is being designed for the particular needs of women inmates. To find out more about what New Hampshire's new prison may be like, NHPR visited a women's prison designed by the same architect, and with the same principles -- in Windham, Maine.

For two decades, feminist researchers and activists have been re-thinking treatment programs at women's prisons, which too often merely replicated what was offered in larger men’s prisons. But unlike male inmates, 90 percent of women who end up behind bars have histories of sexual and domestic abuse. They’re also more likely to suffer from mental illness and addiction than their male counterparts.

So researchers began advocating for a “gender responsive” approach to female incarceration - programs and officer training that took into account women inmates’ histories of trauma.

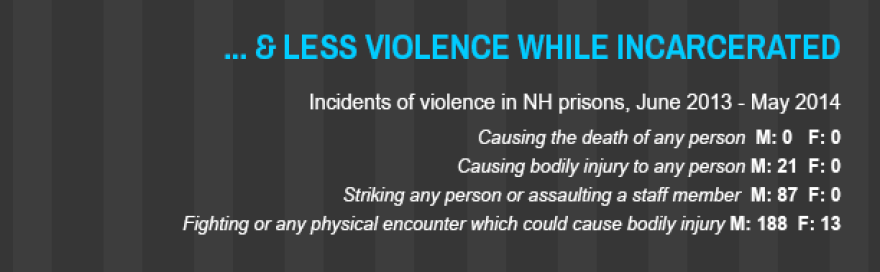

GRAPHIC: Click here for our full prison data graphic

A different feel

New Hampshire’s state prison for men is a pretty typical prison. It’s crowded, there’s not a lot of natural light, and inmates can’t leave their cinder block units without permission. The new women’s prison will be built right behind the men’s prison in Concord, but it will feel quite different.

The design of the prison itself is still in flux: it may turn out to be multiple buildings, or a single building with multiple wings. Either way, Deputy Commissioner of Corrections, Bill McGonagle says, the housing units will look out over a large outdoor area with security fences concealed, “so as you look around the courtyard, it won’t be obvious that’s where you are.”

The lead architect on the project is Arthur Thompson, with the firm SMRT. Twelve years ago, Thompson designed the women’s unit at the Maine Correctional Center in Windham, Maine. The unit, which houses minimum- and medium-security inmates, is considered a national model for gender-responsive prison design.

There, women have keys to their rooms. In an open lounge area, a few women watch TV on upholstered couches with wood coffee tables.

The “soft materials and natural light [are] really important aspect[s] of making this a natural environment,” Thompson says.

Also important, he says, are the wood doors. In a traditional prison, inmates live amongst a constant cacophony of steel doors echoing against cinderblock -- sounds that can trigger stress reactions for trauma survivors.

The environment makes a difference for Kara Bouchard, a 27 year old mother of two who is doing 9 months for theft by deception. “When I walked through the doors I was like ‘this doesn’t look like a prison!’” says Bouchard.

You still lose your dignity, she says. On arrival, everybody’s strip-searched and told to squat and cough. But now that she’s settled in, the environment makes it easier to focus on her anger management, personal healing and community college classes.

Of course, getting equal access to those kinds of educational opportunities brought about the building of a new women's prison in New Hampshire in the first place. The current women's prison in Goffstown doesn’t have space for vocational or educational classes.

Women and relationships

Jodi Holmes is 53 and three years into a six-year sentence at The Women’s Center in Maine for committing aggravated assault while on probation from federal prison. Holmes says in the multiple housing units at the federal prison created a sense of community she doesn’t experience in Windham.

McGonagle says strengthening relationships among the inmates is one of the goals of the gender-responsive approach. He says it’s not clear yet if New Hampshire can afford multiple buildings -- but he hopes open spaces inside the building will encourage that kind of interaction. While routines at men’s prisons usually discourage inmates from interacting with each other, “women want to be more relational,” McGonagle says, “and their connections with other women – it’s one of their strengths.”

A more open design has drawbacks, says Alyssa Benedict, who consults with prisons on gender responsive programming. Benedict says a prison with more open spaces requires more and better-trained officers. “You have to train your staff to understand female development, how they relate to each other,” she says, “and how to as a staff member insert yourself in a skillful way to create safety.”

Jodi Holmes and Kara Bouchard both agree that the open spaces create opportunities for ridicule and harassment among inmates. Holmes says she was “ridiculed and treated very badly” for her entire first year at Windam.

Bill McGonagle says staffing at the new prison in Concord is still in question. The Concord men's prison next door is chronically understaffed, with officers required to work two or three 16-hour days a week.

The department has requested increased personnel for the new prison, but increased staffing will be subject to future legislative budget debates.

A different paradigm

Lawmakers funded the new women's prison after decades of debate over parity for women inmates. They had lacked, as McGonagle explains, “access to recreation classrooms both for vocational classrooms, science classrooms, regular education classrooms.”

But Alyssa Benedict says opportunities to build relationships; and access to safe, quiet environments shouldn’t be limited to female inmates. “It’s almost why we need to tackle the prison paradigm gender aside, on some level,” she says.

However, any changes to the men’s prison are unlikely in New Hampshire.

Construction crews break ground on August 18. The prison is slated to open in October 2016.