New Hampshire's Great Bay and the Piscataqua River estuary have been in bad shape for years – and the latest data doesn't show a lot of improvement.

But scientists say there's still hope for the watershed, and they're trying to home in on things people can control.

The University of New Hampshire's Jackson Estuarine Lab is on Adams Point in Durham, jutting out into the mouth of Great Bay. When I meet coastal scientist Kalle Matso out on the lab's icy dock, there's snow on the shores, and bright sun flashing off cold, blue-grey water.

It's beautiful, but underneath, Matso says it's hiding big problems.

Note: Scroll to the bottom of this story to read the full 'State of Our Estuaries' report

"Did you ever know anybody who looked really good, like, physically you just look at him or her and say, 'Wow, they're in real shape,' and then you find out they're struggling with a tough health problem?” Matso asks.

“That's our bay. Look how beautiful it is, right? Doesn't it look great? Under the surface, there's some issues."

For at least 20 years, he says, the bay has been losing things that hold it together and keep it clean, while getting clogged up with bad stuff that's making those issues worse.

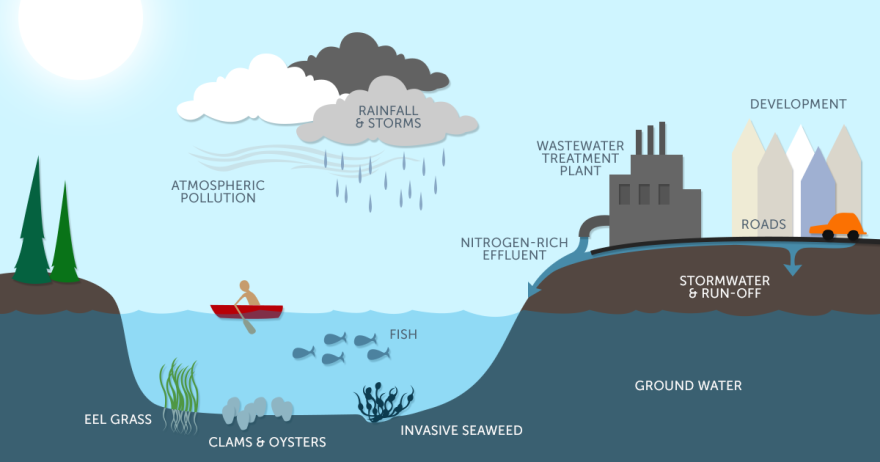

The Great Bay Ecosystem (Click to enlarge)

An estuary is the place where freshwater rivers and streams meet the salty sea. The Seacoast’s Piscataqua River estuary flows through Great Bay – and its health has been declining for years. Nitrogen, harmful in large quantities, enters the bay in treated wastewater and runoff from housing and business development. The bay and groundwater are further contaminated by stormwater runoff from roads and other surfaces, and particles in atmospheric pollution from power plants, industry and cars. All of that is bad for eelgrass, clams and oysters, which are supposed to hold the bottom of the bay together. Without them, that sediment gets weaker and invasive seaweed moves in, making a bad habitat for fish and other critters. And the bay becomes more disturbed by big storms and rainfall, both expected to increase as the climate changes.

Matso says that has an impact on the creatures that call the bay home.

"We count on being able to catch fish here, and being able to harvest nice-tasting oysters and nice-tasting clams,” he says. “And we count on the system buffering us from big storms."

When a big storm comes through, it pushes runoff from the land into the water, and churns up mud from the bottom.

'It's like having a lawn that's just dirt, as opposed to a lawn covered with nice grass.'

In a healthy estuary, there'd be plenty of eelgrass down there, and beds of clams and oysters. Together, they make the mud more solid, help the dust settle, and clean everything out.

"Well, without all the shellfish and the eelgrass, you lose your buffer,” Matso says. “It’s like having a lawn that's just dirt, as opposed to a lawn covered with nice grass."

Those buffers are what this bay has been losing – 90 percent of its clams and oysters, and at least 50 percent of its eelgrass since the 1990s. Meanwhile, invasive, aggressive seaweeds have been moving in.

Seaweed Invasion

Matso pilots us out onto the bay in a little skiff to look for those seaweeds. We soon pass a rocky beach covered in the kind of seaweed I think of as kelp.

"That's not the kind of seaweed we were talking about before – there's nothing wrong with that,” Matso says. “Nothing's as simple as you want it to be. It's not like all seaweed is bad, or all seaweed is good."

He says the bad kinds lurk deeper down. The bad kinds are invasive – they grow fast, die fast, and eat up all the oxygen that fish and other bay critters need to survive.

In a few feet of water, Matso sticks a rake down to the bottom, where there should be lots of eelgrass. He brings up just a tuft of it with a glob of muck around its roots.

'Nothing's as simple as you want it to be. It's not like all seaweed is bad, or all seaweed is good.'

"So now we're getting some more seaweed,” he says. “It's some of the stuff that has less structure, and it's all tied up in the sediment, so you don't really see it.”

He picks apart the mud to reveal one piece of seaweed. It's made of thin branches that tangle around the eelgrass and its roots.

"There can be huge, huge piles of it down there,” Matso says. He’s pulled out clumps of seaweed the size of a basketball in the past.

Twenty years ago, he says, it was not like this. That's when he was getting his master's degree from UNH. By the time he came back, the health of the bay had declined considerably.

"I came out here in 2015 and started snorkeling and diving and I was like,

Wait, what's all this seaweed? I never used to see all this seaweed out here,’” he says.

Taking Control

To recap – the seaweed invasion crowds out the eelgrass, along with the oxygen and shelter that grass creates for little creatures. But it also makes life worse for Great Bay’s few remaining clams and oysters.

It's a vicious cycle – less eelgrass and shellfish plus more seaweed means the water stays muddier after a big storm. That blocks out sunlight, which the oysters and eelgrass and everything needs to bounce back.

"These are sort of classic signs of degradation, and we can't say exactly what's going on, but we know that we're under assault by a suite of stressors,” Matso says. “So if it was your friend, what would you say? You know, you'd say, 'Improve the things you can.'"

'We can't say exactly what's going on, but we know that we're under assault by a suite of stressors.'

Remember, he said the estuary is like your friend who's really sick. He says that friend would need more testing, more information, and more help with as many problems as she could control.

For the estuary, the caretakers are the communities around it. And they have made some progress reversing the bay’s trajectory.

Coastal towns have spent millions to upgrade their wastewater treatment plants, which used to dump harmful nutrients into the water. More land is being conserved near shore, which helps with runoff. People are slowly planting more oyster beds, and removing river dams that block fish migrations.

A Resilient System

Matso says Great Bay and the Piscataqua River estuary are not beyond repair.

"There's very little science to suggest that we can’t recover,” he says. “What the science suggests is that recovery is hard."

As we head back to the dock, he says scientists still have lots of research to do on eelgrass, shellfish and floating sediment. And he says towns need to try to contain the sprawl of new developments, and better manage their septic systems and storm water runoff.

"That's what the community has to decide, is: Given that situation, what do we do?” he says. “We know these stressors are here and they're going to continue – climate change and more storms and these sorts of things – so we want to be as resilient as possible.

“And you look around and see how beautiful it is, and that’s an incentive in and of itself,” he says.

Now that their latest studies are done, the estuaries partnership plans to go over their new data with local officials, hoping to give them ideas on how to help.

Read the full report here: