Recent polls have Hillary Clinton trailing Bernie Sanders in the Granite State Democratic presidential primary, but that hasn’t stopped New Hampshire Democrats from joining forces to raise money with the former Secretary of State.

The news, reported this week by the New York Times, has raised eyebrows among those who suspect the arrangement represents an implied endorsement of Clinton by the New Hampshire Democratic Party, more than five months before the first-in-the-nation primary. The Democratic Parties in Wisconsin, Mississippi and Virginia have similar arrangements with Clinton's campaign.

So what, if anything, does it mean? Here’s what you should know.

These kinds of agreements have been around since the 1970s.

Joint fundraising committees, or JFCs, like the one formed by Hillary for America and the state Democratic Party, streamline the process of collecting and distributing political contributions.

For example, one or more candidate committees, a political-party committee and a PAC will form a joint fundraising committee. That allows donors to cut one check to the joint committee, which in turn distributes it to the participating committees.

How much the JFC can contribute to the other committees is bound by limits established by the Federal Election Commission. In 2016, the JFC can give up to $2,700 to the candidate committee, $10,000 to the state party committee and $32,400 to the national party committee.

Joint fundraising committees are common

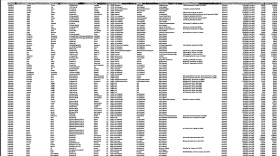

During the last presidential election, in 2012, there were nearly 500 active JFCs, most of them set up by members of Congress. All told, according to the Center for Responsive Politics, they raised nearly $1.1 billion.

More than $900 million that year was raised by JFCs set up to help President Barack Obama and the Republican nominee Mitt Romney, so-called "Victory" funds. Romney's JFC shared its haul with, among others, the Republican Party of Idaho and the Republican State Committee of Massachusetts.

The Obama Victory Fund raised money for 11 state Democratic party committees, including New Hampshire's, which received close to $1.2 million.

Thanks to the Supreme Court, joint fundraising committees are now like Super PACs – vehicles for unlimited donations from the wealthiest donors

In the past, donors to JFCs were bound by campaign-finance regulations that capped aggregate contributions. In 2014, for instance, donors could give to as many candidates and committees that they wanted to, but their contributions could not exceed $123,200 total.

In April 2014, in McCutcheon v. FEC, a majority of Supreme Court justices decided those aggregate limits were unconstitutional.

Donors in 2016 must still abide by to limits to individual candidates ($2700 per election), national party committees ($33,400), state parties ($10,000) and traditional PACs ($5,000).

But they no longer have to stop when their total contributions reach $123,200. Theoretically, a donor could contribute to a JFC set up to benefit every Republican or Democratic candidate for federal office in a given year, along with every party committee, which would add up to about $3.5 million.

McCutcheon is more unpopular with some campaign finance reformers than Citizen United

The Supreme Court’s 2010 decision in the Citizen's United v. FEC case overturned a ban on independent expenditures – that is, spending that is not coordinated with a particular campaign – by corporations and unions seeking to influence elections.

Citizen's United opened the door for non-candidate and non-party political committees to collect unlimited amounts in contributions. But, in keeping with previous decisions, the court kept in place limits on the amount an individual can give to political candidates and parties.

In McCutcheon, the justices ruled it was unconstitutional to limit the total amount any individual could give throughout an election cycle. Reform advocates say the decision will bring back the "soft money" that was extinguished by the McCain-Feingold reforms of the early 2000s. Without those aggregate limits, they argue, political parties, which are largely the domain of elected officials, can now could raise and spend unlimited amounts.

The Clinton-NHDP fundraising agreement is not necessarily a sign that the state party is, as many Republicans contend, casting its lot with Clinton over other candidates

Ray Buckley, longtime chairman of the New Hampshire Democratic Party, says he offered similar deals to other Democratic candidates for president, including Bernie Sanders, Martin O'Malley and Jim Webb, but received no response.

In any case, the state party can spend the money raised through this arrangement however it wants, regardless of who wins the party's presidential nomination. Buckley says the money will be used for field operations - get out the vote, voter identification and the like - during the general election. There is nothing stopping the state party from using the money to help the eventual nominee, along with any down-ballot candidates the Democrats field in 2016.

That said, there is little doubt that, notwithstanding Sanders performance, Clinton is the presumptive nominee at the moment. And no other candidate in the Democratic primary can raise money like she can: in less than three months, Hillary for America collected $45 million from donors, while a Super PAC aligned with the campaign raised another $20 million.

It's probably worth noting that, on the stump, Clinton has talked about the need for campaign-finance reform, going so far as to suggest a constitutional amendment to overturn Citizen's United.

But her campaign's deal with the New Hampshire Democratic Party indicates that, until then, she'll play by the rules as they exist right now.