Sometime next year an official with the White Mountain National Forest will try to answer a complex question: How wild should the wilderness be?

The issue is whether to remove – or replace - a decrepit bridge in the Pemigewasset Wilderness Area.

Some hikers worry removing it will make crossing the East Branch of the Pemigewasset river dangerous. But it would also make the wilderness a little wilder, more special and more challenging. And, that’s basically what Congress intended in 1964 when it passed The Wilderness Act.

The goal of that act, Congress said, was “to secure for the American people of present and future generations the benefits of an enduring resource of wilderness.”

Getting to the Thoreau Falls Bridge is about a six-mile hike from the Lincoln Woods Ranger station just off the Kancamagus Highway.

Upon reaching the 60-foot bridge there’s a big, attention-getting sign: “Weight Limit: One Person At A Time.”

Walk across it and there’s a slightly disconcerting flex and bounce, more than normal on such a bridge. The water’s eight to 10 feet below.

It is no surprise that in 2011 a U.S. Forest Service engineer concluded that geriatric structure was not safe. It wasn’t just old, it has also been damaged by Hurricane Irene.

It was built in 1962, part of The White Mountain National Forest. Twenty-two years later Congress declared the 45,000 acre area in which its sits the Pemigewasset Wilderness Area.

That was a huge change. It meant the area was under the 1964 federal Wilderness Act. The goal of that act, Congress said, was “to secure for the American people of present and future generations the benefits of an enduring resource of wilderness.”

And basically the act says there aren’t supposed to be any motorized vehicles, power equipment or man-made structures – like a new bridge.

So, the log bridge crossing the East Branch of the Pemigewasset River should be dismantled – by hand – and draft animals should be used to remove its pieces parts.

“This is a classic example of a bridge or structure that pre-dates wilderness, comes of age and then we have to make a decision on what to do,” says John Marunowski, a back country and wilderness manager with the U.S. Forest Service.

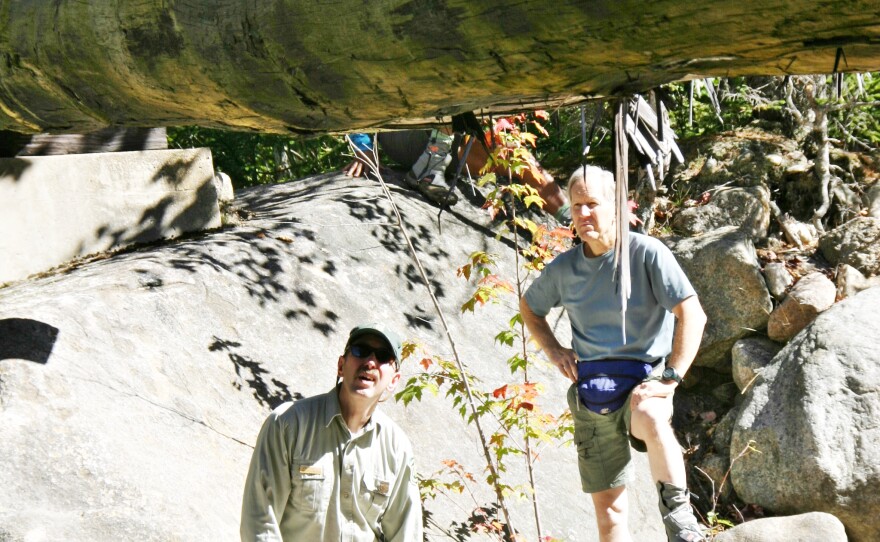

On a recent Saturday he’s addressing a group of hikers that he and Jon Morrissey, the ranger in charge of the Pemi district, escorted to the bridge to hear their thoughts – and share theirs.

That’s important to Morrissey because he will decide whether the bridge – too far gone for repairs - will be rebuilt.

But he doesn’t have much wiggle room, says Jan Laitos, a law professor who specializes in environmental law at the University of Denver.

“The Wilderness Act is actually fairly inflexible,” said Laitos.

But under the act there is one possibility for putting in a new bridge: if it is needed to protect hikers from a serious hazard. And trying to cross the river in high water is one of the things that concerns some hikers.

The hikers are standing around chatting, munching sandwiches or apples, looking at the bridge and imagining it being gone.

They are talking about crossing the bridgeless river during high water or in the winter, because the Pemi is popular with long-distance cross-country skiers.

Sam Jamke is a volunteer trip leader with the Appalachian Mountain Club, and she’s worried about fording.

“Right now, certainly in this location, even with this low water that is impossible,” she says.

Part of the concern is that People who have hiked for miles and miles may be reluctant to back track. So, they may risk a crossing even in high water.

As the lunch break goes on there’s a civil and mildly spirited back-and-forth between the eight hikers and Morrissey and Marunowski.

Jamke, the AMC trip leader, wonders whether removing the bridge will also restrict access to the largest wilderness area in the Northeast simply because some people will be reluctant to take a chance fording the Pemi.

“I don’t know that is really the intention to restrict access as it is to restrict development. That’s different. Those are different goals,” she says.

Marunowski suggests another way to look at it. "We're not restricting access, we're changing access. If the bridge weren't here, yeah, you might be taking off your socks and shoes and fording the river," he says.

Jamke jumps in: “And drowning? People will try anything.”

Those who favor removing the bridge say it would uphold the spirit of The Wilderness Act.

And Marunowski says wilderness areas should be unique, different than the rest of The White Mountain National Forest.

“It sets it apart, it makes it different. It makes it challenging. It sets you up to expect a different experience.”

“A lot of people think in The Wilderness Act that means fording rivers is part of it. That is part of the challenge, part of the risk of being out in a wilderness area.”

Larry Garland, of Jackson, doesn’t see a wilderness area and a bridge as incompatible.

“I doubt that people would complain there is a bridge here,” he says. “A bridge per se isn’t necessarily anti-wilderness.”

Among those who want the bridge replaced is Sen. Jeb Bradley, a Republican from Wolfeboro and an enthusiastic hiker.

“Bridges are there for a reason. People will make unsafe decisions in crossing rivers that they shouldn’t,” he said in a telephone interview.

In August, Bradley asked Republican Sen. Kelly Ayotte to help. Last month she wrote forest officials urging the bridge be replaced. The Appalachian Mountain Club also wants a new bridge saying it would provide “an important link and safe crossing in a very special place.”

Jan Laitos, the Colorado law professor, says pre-existing structures in wilderness areas are a national issue. And, he says there’s no trend when it comes to decisions. Decisions vary depending on location and circumstances. But safety can be a major factor.

“In that New Hampshire wilderness area if that is a river that sometimes floods or has high water where people cannot cross or worse they would try to cross in high water and get swept away that would definitely be an argument for replacing that bridge,” he says.

Morrissey says there are plenty of issues to consider, lots of suggestions and comments from the public and he’s in no rush. He wants to make the right decision and that won’t happen until sometime next year.