On its face, the Free State Project is pretty simple. It’s a political experiment, an organization that aimed to assemble a group of 20,000 Libertarians, and move them en masse to a single state, where they can pursue the maximum freedoms of life, liberty and property.

But if you’ve heard of the project, you’ll know that defining exactly what “liberty” and “freedom” means to the people involved can be more complicated to pin down.

As part of our continuing series Only in New Hampshire, in which we answer your questions about New Hampshire and your Granite State community, we're tackling a big one sent in by a listener named Erin: What, exactly, is the Free State Project?

So let’s start at the beginning.

Note: NHPR's Word of Mouth is dedicating an entire show to this question which will air on Saturday, April 14th at 11 a.m.. You can listen to that show here, or on the Word of Mouth podcast.

Related story: What Makes People Move to N.H. to join the Free State Project?

A simple plan

Jason Sorens is the founder of the Free State Project. When I spoke to him, he kept his hands clasped tightly in front of him, like he was waiting to say grace at Thanksgiving Dinner.

"I was in sixth grade and I was young for my grade and small for my age. And also just kind of awkward and in a new school and I got kind of picked on a lot," he said.

"And one day, I got pushed down into the pavement by this kid who ran up behind me and chipped my tooth. And we went to the principal's office and the principal forced me to sign a confession saying that I had kicked this guy."

Jason told me he did sign the confession, but didn’t actually do the kicking.

"We were new to the community and I later figured out this guy, or found out that this guy's mom, was on the school board, and so, that introduced me to this idea of, 'Oh there's politics here,' and there are people who will use power and abuse power, and that may have primed me for that kind of skepticism about people in authority."

Today, Jason doesn’t look so much like a revolutionary as he does a young IRS auditor. A lecturer at Dartmouth, he’s bookish with great posture. And although he's over 40, he could easily pass as a student.

'There are people who will use power and abuse power, and that may have primed me for that kind of skepticism about people in authority.' - Jason Sorens, founder of the Free State Project

And Jason is a devout "small-l" libertarian, or as many in the movement prefer calling it, a "liberty activist."

Traditionally, libertarianism blends small-government fiscal conservatism - free trade, low taxes, and maybe something about the gold standard - with a mixed bag of sometimes-socially liberal policies like fewer drug laws, more gun rights, and acceptance of gay marriage.

The Libertarian Party has been around since the 1970s, but, as a third party, has never been able to rack up many political victories.

As a PhD student in political science at Yale, Jason was studying independence movements in other countries and thinking about his own beliefs. And it was then he decided it was time for libertarians to adapt.

“Libertarian activists need to face a somber reality,” he wrote in an essay in 2001, " Nothing’s working.”

Jason's essay eventually became the founding document of the Free State Project. In it, Jason proposed a mass migration, a voluntary resettlement of 20,000 Libertarians, anarchists, anarcho-capitalists, pacifists, even freedom-minded Democrats and Republicans, to a single, low-population state, a place they'd have the electoral power to transform it from the inside.

"I sent it to a fairly obscure online journal called The Libertarian Enterprise," Jason said. "The editor said he wanted to sign up, and it kind of went from there… and evolved from there."

His idea promised Libertarians a much-needed political win. Only at the end of the essay does Jason seem to acknowledge the challenges his idea might face.

“Certainly, there will be inconveniences,” he wrote. “We might have to move away from friends and family; there might be spells of unemployment; we might have to take careers that are not our first choice. But I can't believe that we've gone so soft that we won't tolerate these inconveniences for a possibility at attaining true liberty. Our forefathers bled and died - because of the Stamp Tax! The Free State Project requires nothing of that kind, and the stakes are so much higher. How much is liberty worth to you?”

It was an inspiring moment, in an an otherwise academic piece. But central to the essay’s main thrust is an argument that has plagued Jason, and the Free State Project, ever since.

"You know, I mention the idea that maybe we could threaten to secede in order to get more autonomy, because this was what I was working on - seeing this could work in other countries."

Later, Jason and other Free State Project members would try to distance themselves from these arguments, but it’s undeniable: The earliest roots of the Free State Project were, in part, about finding a state that could declare independence from the United States.

A secession enterprise

The online journal that published Jason's essay, The Libertarian Enterprise, has the words, “Let’s Secede!” in red cursive letters at the top of the homepage.

The site is run by science fiction author and self-professed freedom-fighter L. Neil Smith, who has published three books about the Star Wars character Lando Calrissian, and who's no novice when it comes to publishing insults and hurling epithets like, "bloated tax-vacuums," "bottom-feeding socio babblers," and "whimpering cop-suckers" in his writings.

Jason is no such mudslinger. But in the days after the essay went out, Jason found himself in charge of a rambunctious band of frustrated Libertarians, many of whom were very excited about the idea of withdrawing from the union.

"It was very fast. Within about two weeks about 200 people emailed me and said they wanted to participate. We set up something called a Yahoo club...and we got together and started hashing out the details."

That "Yahoo club" is actually an online message board with thousands of chat threads that can still be accessed online.

Central to the group's earliest chat debate is the language of 'the pledge.'

The pledge would be the what bound new Free State Project (or FSP) members to the mass migration. It’s what’s called an Assurance contract - a voluntary agreement that people are on the same page.

But within 24 hours of the formation of the Yahoo group, major disagreements over what the pledge should contain start to pop up.

User Johnny_magic2001 said the FSP should back-up their secession language with the threat of military force.

Jason, ever the diplomat, wrote that secession would have to be electoral - no state could withstand the feds, should things go south.

“If I were single,” Jason wrote, “I might be willing to risk life & limb… but my wife would never agree to this thing if she thought violence might be involved. ;-)"

I asked Jason about some of the content I found in those early Yahoo chats.

"I'm a little surprised you mentioned it, because there’s some pretty cringy stuff."

"Yeah I suppose there is. I dunno. I haven't looked at it in a long time."

Having those chats living online, though, it's a bit like seeing how the Free State Project sausage got made. Jason doesn't disagree with that.

"Yeah, it’s a conversation among people trying to put something together, and are speaking among themselves and not for some external audience so there’s nothing filtered there. I’d rather be transparent than not."

How the sausage got made

The most frequently discussed topic from the Yahoo group chat has to do with which state should be selected for the Free State Project. New Hampshire becomes a favorite option almost immediately.

User JFTonne disagreed. New Hampshire is being invaded by Massachusetts liberals, she said, and should it get selected, she’s out of the group.

Diane - who wrote under the username Modern_Antigone - says she’d prefer a warm weather state. “I can’t imagine even noticing my freedom, for being cold.” she said.

On the one hand, the messages reveal a blossoming grassroots movement, where users have a nearly limitless amount of initiative. Volunteers step forward to research states and to share state data.

But on the other hand, it’s total chaos.

"It was a true marketplace of ideas," Jason told me. "People had all sorts reasons for picking a state. Some were good. Some were implausible."

About a week after launching the Yahoo group, Jason posted a follow up to his original essay, also published in the Libertarian Enterprise.

Emphasizing secession may have been a mistake, he wrote. It’s a tool to lower federal intervention....one of many…and not necessarily the end game.

In the years since the group started, Jason has turned away more fully from the secession idea in both his rhetoric, and his research. But at the time, secession was a big part of what brought this group together, for better or for worse.

One of the early leaders of the Yahoo group page is a user named Vroman18, who helped Jason by setting up the very first Free State Project website.

After one particularly problematic discussion about ethnicity led one chat member to condemn all forms of bigotry, Vroman18 piped in:

“I plan to pitch this idea to confederate loyalists and such,” he wrote, “provided they’re not neo-nazis on the side. You forget how big a number 20,000 is… we need members.”

"Yeah that’s pretty cringe-y," Jason agreed when I asked him about the post. "Is that something Robert said?""

"Yeah, you play more of a moderator… and emphasize that racism and bigotry isn’t allowed."

"Yeah, I would say we never had white separatists in the FSP. That would be in violation of our policy," Jason told me. "I mean, I think Robert was expressing his viewpoint, but that wasn’t really a part of the FSP."

"Do you have any sense of how many people, from that initial few hundred, are still in the group?"

"Good question. A handful of people? I would actually say the large majority of those in the initial discussion are no longer active in any way."

By September 1st, 2001, the debate was over.

The bylaws were written, and a slogan was made: “Liberty in our lifetime.”

The Free State Project even had a logo, a simple cartoon porcupine.

Most important, the group had finalized the language of the pledge. It was vague, open to interpretation, but ultimately simple, and just one paragraph long.

Once enough participants signed up, and the state had been selected, Free Staters would have five years to move, at which time they pledged:

I hereby state my solemn intent to move to ________ within 5 years after 20,000 Participants have signed up. Once there, I will exert the fullest practical effort toward the creation of a society in which the maximum role of civil government is the protection of individuals' life, liberty, and property.

So what exactly did the pledge mean? Well, that was up to whoever signed on the dotted line.

A festival of porcupines

By 2003, when the Free State Project voted to move to New Hampshire, they had only gotten 5,000 signatures - well below what they were hoping for by that point.

But they were also attracting a new brand of activist, people like Carla Gericke.

Carla told me she went to an all-girls boarding school in Pretoria, in what she describes as the "heyday" of South Africa's police state. She said that one day, the police showed up on her school's campus.

"They came in and they detonated firebombs and told us there was a terrorist attack. And then afterwards they were like, 'Yeah that was a drill.' And I mean, I was like 11 and I didn't know it was a drill. I was traumatized by that experience."

Carla moved to California with her husband in her early 20s and spent the next few years working as a lawyer during the dot-com boom. She got her citizenship in 2000.

Later, she says she enrolled in an MFA program at City College in New York, where she was pretty much the only Libertarian.

These days, Carla identifies (and is running for office as) a Republican, but when she talks about how she found her way to libertarianism, she sounds like she has more in common with the left.

'This is the thing...we actually think Bush and Obama and Trump and Clinton are all equally bad.' - Carla Gericke, former President of the Free State Project

"Where did the antiwar activists go when Obama got elected? I mean, that broke my heart. You know, I felt like I built a really good alliance with a lot of people when...Bush was in power and you know, this is the thing, like we actually think Bush and Obama and Trump and Clinton are all equally bad."

The Free State Project officially sponsors two annual events in New Hampshire. One, called the Liberty Forum, is a more formal, hotel convention-style affair. The other is The Porcupine Freedom Festival, or Porcfest - a big, weird weeklong libertarian party that’s held in a campground in Lancaster, New Hampshire.

"I think my first Porcfest was, oh… 2006," Carla told me. "I would say the majority were older gentleman with long wide beards who were open-carrying guns. This was something that was entirely new and foreign to me. It was World Cup soccer. And my husband, you know, would go to very dry economic talks and I was like...I'm just going to go to the hotel and watch some soccer."

But she must have got something out of Porcfest, because after she finished her MFA, Carla moved to New Hampshire and took over organizing the event.

Video: Jason Sorens in scenes from Porcfest, 2009

Eight years under George W. Bush had brought a lot more color to the liberty movement, and added a lot more political fuel to fire Free State rhetoric, like the Patriot Act, Abu Ghraib, and Guantanamo Bay.

"So I think a lot of times there’s one thing that triggers people, and then they’re like 'why did this one thing happen to me,'" Carla explained. "They start to look, and they start saying like, 'Wow, this is happening from a criminal justice perspective… a surveillance perspective…' for me, it was filming cops."

Watching the watchers

Filming cops - or pretending to film them, anyway - could wind up being Carla's biggest contribution to history.

In 2010, Carla Gericke says she was following a friend in her car one night through Weare, New Hampshire, when a squad car pulled up behind her. She says she pulled over, and the officer told her to drive away because he was actually pulling over the car she was following.

'Government is force. And what I mean by that is for every law we write it is backed by the barrel of a gun. If you refuse to do whatever's in that piece of paper and you keep saying I won't do it someone will eventually show up at your house with a gun and make you do it.' - Carla Gericke

"The officer told me to leave and I was like 'Well, I can't leave because I'm following them and I've no idea where I am, it's 11:00 at night. It's dark, you know. No I'm going to stay here.' But he really was a bit on edge so something was weird and I was just like, OK, something's weird."

At this point, Carla pulls out a video camera. For some reason, it wouldn’t record, but she got out of the car and started pretending to film the police anyway.

They told her to get back in her car, and then a second officer showed up and asked her where the camera was. She refused to tell him, and refused to hand over her license and registration.

"So things escalated. I was arrested. The people in the car that I was following got arrested and at the police station the police officers refused to give me my camera and they refused to give me a receipt to say they had taken my camera, and so I got a little stroppy and that's when they decided to charge me with wiretapping."

Carla told me this experience - of being told she could not document the actions of a police officer - re-affirmed everything Carla knew about the state. Not just New Hampshire - the very concept of a state.

"Government is force. And what I mean by that is for every law we write it is backed by the barrel of a gun. If you refuse to do whatever's in that piece of paper and you keep saying I won't do it someone will eventually show up at your house with a gun and make you do it."

It’s a philosophy shared by many liberty-minded folks. But decisions about how individuals should respond to that force - and which laws they choose to follow or fight - aren't anything close to unanimous among Free Staters.

Carla chose to fight her arrest by suing the town of Weare, and the officers who arrested her.

Other Free Staters fought by showing up town hall meetings. Others just lived and worked like everybody else - but occasionally got together to discuss and debate libertarianism.

But one group of Free Staters was attracting a lot of attention. Because they were fighting just about everything.

The tale of the Free Man

Ian Freeman's birth name is Ian Bernard. He had it changed in probate court a few years ago. He looks a little bit like David Tennant from Doctor Who, if Doctor Who wore a goatee and backwards hat.

Ian is the main host of Free Talk Live, a radio show he started in 2002. The show's topics range from guns to video games to public schools, and whatever else Ian and his co-hosts want to talk about.

Related: Click here to read earlier NHPR stories featuring Free Keene's Ian Freeman

Whatever the subject, the level of intensity on the show remains a constant. In one episode, they talk about the arrest of a raw milk producer for about 20 minutes. It’s enough to inspire a caller to suggest it’s time for revolution.

"If that means something that could result in mass casualties," the caller says, "well you know what, I think it’s about time to do it..."

Ian had been following the Free State Project since its early days, and a few years in, he liked what he was seeing, particularly in Keene, a college town not far from Mount Monadnock.

In 2006, he got on board, and snagged a mutual sponsorship agreement with the Free State Project. He got free tickets to Porcfest and other events, and they got free on-air promotion.

Around the same time that Carla was first showing up to Porcfest, Ian was already stepping up his liberty activism in Keene.

He and a gaggle of other Free Staters chalked pro-Libertarian message on the city sidewalks, gathered in state liquor stores and sang carols with Libertarian lyrics, and started meeting every day to smoke pot in Keene's picturesque town square, right in the shadow of the United Church of Christ.

And while Ian wasn’t involved in all of it, almost all of it was written up in Ian’s YouTube page and blog Free Keene.

In an article called 150+ Reasons to Move, Ian called Keene's central square a “demilitarized zone” for cannabis usage.

Not that Free Staters weren’t getting arrested, which is why Ian describes another reason to move: “If you’re going to do civil disobedience, Keene is a great place to get jailed, all things considered.”

Ian's group took the activism to court too, refusing to stand for judges, filming inside the courthouse, and generally making enemies of city employees. And while all that attention helped get the name of the Free State Project in the news and the Free State pledge in front of prospective eyeballs, the press in mainstream outlets was often negative, or sometimes just confusing.

'If you're going to do civil disobedience, Keene is a great place to get jailed, all things considered.' - Free Keene's Ian Freeman, in an essay called 150 Reasons to Move

All this mattered to Carla, because in 2011, she became president of the Free State Project.

"I had a very short punch list of things I wanted to accomplish," Carla said. "One was to get the 20,000 people to sign up, to continue to encourage people to move to New Hampshire in the meanwhile... And the third one was, I was like, 'I want to meet Edward Snowden.'"

Both Carla and Ian signed the same pledge to "exert the fullest practical effort towards liberty." But it seems they're not on the same page about the meaning of the word “practical.”

Not-so merry men

Of all of the stunts that Free Keene pulled, the one that has gotten the most attention was something they called “Robin Hooding.”

A handful of activists, including Ian, would feed expired parking meters to prevent meter maids from handing out tickets.

On its face, it sounds pretty nice. Until you see the footage.

In a lot of these videos, two or three people surround the meter maids as they walk. They use walkie talkies to coordinate location. They’re like weird, reverse bodyguards.

But while all this was going on, Carla was engaging in her own brand of activism. She protested the city of Concord’s purchase of an armored military vehicle called a Bearcat. She wrote pro-liberty op-eds to the major New Hampshire newspapers.

And in 2014, she settled her lawsuit with the town of Weare, which made it all the way to the 1st Circuit Court of Appeals.

Her case - one involving the right to film law enforcement - should have been the Free State Project’s biggest victory of the year, especially given the growing general public anger over police shootings of young black men.

But just a couple months later, Free Keene managed to overshadow that story by getting their own national press - on Comedy Central’s "Colbert Report."

Ian doesn't think his kind of action hurt the Free State Project, despite some of the feedback he's gotten.

"It's just funny. It's just people being made fun of. And you know it's interesting some of the response to that from some libertarians like, you guys are ruining the movement. I can't tell you how many times I've been told that."

After a couple of the meter readers in Keene decided to quit, saying they couldn’t stand being harassed, the city sued Ian and a couple of other Robin Hooders.

But, as it turned out, the Robin Hooders had the law on their side. The city of Keene lost the suit.

"In their public press releases and interviews with the media it was just straight up lies," Ian said, "If they had any evidence that we were harassing their employees, they would have arrested us and charge us with criminal harassment."

'Non-aggressive' people

As I've reported this story, I've grown more hesitant about grouping Free Staters together. So many people came to the movement for different reasons, and they don't all stand behind the same tactics.

But many Free Staters do have something in common, ascribing to something called “the non-aggression principle.” Simply put, it's an ethical position that says that violence, or threatening violence against a person or their property, is inherently wrong.

Self-defense, however, is a natural right, should someone else aggress against you.

Theoretically, they reason, if everyone follows the code, everything should be just fine. But if it they don't, some say that's justification for carrying a weapon.

(In case you were wondering, this is why the porcupine is a libertarian icon - it’s the perfect mascot for the non-aggression principle.)

But watching the Free Staters' videos from Keene, it's easy to get the feeling that some Libertarians - like Ian - feel they are under constant threat. And that feeling justifies an attitude of constant vigilance - of perpetual, angry, self-defense.

For Carla and company, that attitude doesn't look very “on-brand."

But then again...who, exactly, in charge of that brand?

A leaderless movement?

Nearly everybody I spoke to from the Free State Project described the movement as “leaderless” or “bottom-up." This is partly true because the movement is largely voluntary.

But there’s also board of directors and some staff. And there are actual Free State Project leaders like founder Jason Sorens, and Carla Gericke.

And they do have the power to kick people out. And they have kicked people out, at least officially.

One of those people is Christopher Cantwell, the so-called “Crying Nazi,” featured in a Vice News documentary about the "Unite the Right" rally and protest in Charlottesville. Cantwell was arrested after that rally.

Related: Read NHPR's reporting on Keene-based white supremacist Christopher Cantwell

Cantwell got booted from the Free State Project in 2012.

But shy of endorsing violence or bigotry, the non-aggression principle - the very philosophy that provide the movement its backbone - is also what makes it nearly impossible for the leaders of the Free State Project to assert any authority over the group.

To many, the ability to hold strong to your principles of individualism, even in the face of behavior you find distasteful, that’s what makes you a true libertarian.

'Maybe someone would say 'I'm only going to open a blacks only bar. No white people allowed here.' They should be allowed to do that.' - Carla Gericke

"Let's take smoke," Carla explained. "So if you believe in property rights then you should believe that the property owner or the bar owner has the right to say this establishment is a smoking or a non-smoking establishment. And if you don't like smoke, don't go there. It's very simple."

"Now, the unfortunate thing is that means in a scenario with racism, maybe someone would say, 'I'm only going to open a blacks-only bar. No white people allowed here.' They should be allowed to do that. It sounds horrible but if we're going to stick to the principles and if we stick to those principles from start to finish the entire world would be a better place because at least we would all know what the rules are."

It might seem surprising that someone could have grown up under apartheid in South Africa and still endorse a system that would allow racial discrimination to flourish. So it's important to point out that Carla is white. And statistically, so are most libertarians.

This also shows just hard it is to characterize the Free Staters as a group, because central to their ideology is an aversion to declaring any idea out of bounds.

But even so, while the Free Keene movement was making headlines for Robin Hooding and other tactics, the Free State Project was trying to attract followers, and Ian didn’t make it easy for leadership.

He criticized the board for kicking out people like Christopher Cantwell, who remained a regular co-host of his radio show, and whom he still associates with today.

Related story: In Keene, Charlottesville Connection Greeted With Discomfort and Dismay

Ian even created his own splinter group – The Shire Society – which, as far as I can tell, is another version of the Free State Project with no official leadership.

A red line?

Aside from directly advocating violence, it turns out there is a red line for the Free State Project. And like a lot of big news for the FSP, it came to light in 2016.

That was the year that Carla achieved her dream of meeting Edward Snowden, who appeared as a speaker at the New Hampshire Liberty Forum via Skype from Russia. Carla was in the front row holding back tears behind a mask of Snowden’s face when he was introduced.

Video: Watch Edward Snowden's Skype appearance at the 2016 Liberty Forum

2016 was also the year that the Free State Project reached its goal of collecting 20,000 signatures. And it was the year that two petitions started circulating online.

Both of them wanted Ian Freeman stripped of power because of his views on the age of sexual consent. One of the petitions, called People Against Pedophile Defenders, featured a clip from Free Talk Live:

Note: The content featured in the audio below might not be appropriate for some listeners

But that clip from Free Talk Live was recorded in 2010, which meant the leadership of the Free State Project had known about Ian’s views on consent for years.

[FSP Founder Jason Sorens says that he, and at least a few other board members, were not listeners of Free Talk Live and therefore were unaware of Ian Freeman's views on age of consent.]

The Free State Project eventually released a statement. In it, they acknowledged Ian Freeman had likely convinced more people to move to New Hampshire than any other single individual.

But they also said they couldn’t risk having the Free State Project associated with discussions about age of consent.

So they ended their mutual sponsorship, and kicked him out. This meant Ian was no longer welcome at Porcfest, or any other FSP events.

Three days later, the FBI raided Ian’s home on the suspicion that somebody living there had been downloading child pornography.

Charges have never handed down in that case. The equipment taken by the FBI, save a camera, has never been returned.

Ian is still the host of Free Talk Live, and there’s been some on-air conspiracy theories about what may have led to the raid. But the Free Keene faction has been a lot quieter since then.

"I don't have any personal hard feelings about it," Ian told me. "I don't hold a grudge if I see Carla. You know I usually hug her and you know, it's always good to see her and she was one of the board members who voted in favor of kicking me out."

But Ian also continues to "pursue liberty" however he sees fit with his own splinter group, the Shire Society. They’re even holding their own summertime festival, just one week before the Free State Project's premiere event, Porcfest.

He's calling the event Forkfest.

Live Free State or Die

While a handful of activists drew much of the public attention around the Free State Project in the years since its founding, other Free Staters were busy working to transform the state's culture - and its legislature.

The Free Staters were among the earliest adopters of cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin, and Dash.

Related story from 2013: Digital Currency Finds a Foothold in New Hampshire

Joel Valenzuela moved to New Hampshire about five years ago.

"I live off of cryptocurrency right now," he said. "A couple of years ago I closed my bank account as part of an experiment. I still haven't opened it back up."

New Hampshire is home to the first Bitcoin ATM, and in Portsmouth, you can even buy a cup of coffee without resorting to the US dollar.

The hallmarks of Free State culture vary, and the so does the geography of Free State communities in New Hampshire. While crypto is big on the seacoast, or 'Freecoast' as they call it, survivalists and off-the-grid types can be found in the North Country, and Free Keene dominates the southwestern part of the state.

In each of these places, liberty-lovers pursue freedom however they see fit, and they pride themselves on embracing the contradictions that define them as a group.

For all the talk of their decentralized organization, Free Staters are both incredibly organized and incredibly independent. Through a spiderweb of forums and Facebook pages, they help incomers unpack, find apartments and jobs.

They give tours to prospective signers, hold regular movie nights, and even have a community center in Manchester nicknamed The Quill.

There are Free State real estate agencies that accept Bitcoin, custom crafters of rifles, Free Stater-owned bars like Murphy’s in Manchester, Free State lawyers, and Free State non-profits.

There are even Free Staters working inside state government.

And if you thought the Free State Project was a just migration of flatlanders, think again. Of the approximately 4,300 Free Staters currently living in New Hampshire, I've been told as many as 3,000 are native Granite Staters who signed onto the project without having to move an inch.

Of course, it's hard to be too precise. This is a group that doesn't exactly love the idea of being tracked.

So what exactly does the label "Free Stater" really tell you about a person? Not much, says State Representative Elizabeth Edwards.

"It tells you that they take their beliefs seriously enough to pick up their lives and move somewhere, which is interesting information. And it tells you that they are skeptical about government power. But it doesn't really tell you anything else because there is so much variety."

I was having trouble getting a hold of Elizabeth, until one of her colleagues told me to text her through an encrypted messaging app called Signal.

Now in her second term in the State House, Elizabeth ran - and won - as a Democrat. She says she made that choice for a few reasons.

"I'm married to a woman and I didn't feel like the most that I wanted to be a part of a party where the most important part of my life was like contradicted by the party platform - that just seemed really like it would be a super uncomfortable situation for me to be in."

In 2006, the first Free State Project participant was elected in the New Hampshire House of Representatives. By 2012, there were 12 Free Staters in the House. Right now, there are 17. That we know of.

All but two of them are registered Republicans.

And while 17 may seem like a small number in the 400-member New Hampshire House, compare it to this: The Libertarian party holds just four seats in state legislatures around the country.

The relative success of the Free State party in the New Hampshire legislature is a testament to success of one aspect of their experiment. They haven't won by running as Libertarians, but by running as Democrats and Republicans.

So, what kinds of laws can Free Staters take credit for? So far, they've led the charge in creating lower-fee nano-brewery laws, repealed the state's knife codes, and passed a bill that grants immunity to users who report a drug overdose to the police.

But consistently voting in favor of more liberty can actually be pretty tricky. Rep. Keith Ammon, a Free Stater from New Boston who was elected as a Republican, told me abortion is a divisive issue inside the FSP.

"Libertarians can disagree on that because they focus on whose rights are being violated or protected. If you focus on the mother, you might be more pro-choice. If you focus on the fetus, the unborn baby, you might be more pro-life."

With this kind of tricky decision-making, it’s no surprise that Libertarians sometimes need a little help figuring out how to vote. That’s why Keith chairs the New Hampshire Liberty Alliance, or NHLA, an organization that rates bills in the house and senate.

A bill increasing privacy rights for genetic data? The NHLA rates it pro-liberty.

A bill requiring companies to pay fired employees their unused vacation time? Anti-liberty.

A bill repeals prohibitions on carrying guns while riding snowmobiles? Pro-liberty.

But his group doesn't rate every bill, and I was surprised to find that Keith and a number of other Republican Free Staters support stricter voter registration laws, for example.

"When you’re there and you actually have to push the button, it’s not easy to parse every bill and be consistent," he explained.

Elected Free Staters don’t always make it easy for their adopted party. Free State legislators make up about half of a newly formed coalition that, in 2017, stymied Republican efforts to pass a budget, a sort of Tea Party deja vu in the New Hampshire legislature.

'By the time I was sworn in, I was just sort of like doubting everything. And at that point I just wanted to do the best job I could. Whatever that meant - and not particularly vote with any agenda or game in mind, even if that meant voting to make New Hampshire less free or in some sense.' - Free Stater and Democratic state rep Elizabeth Edwards

But the Republican Free Staters have had an easier time blending in at the State House than their Democratic counterparts, according to Elizabeth Edwards.

"The libertarians occasionally treat me like a traitor and a good number of Democrats have no idea what to make of me," she said, adding that by the time she won her first primary, the responsibility of being a representative - of really being responsible for constituents out there - started to weigh on her shoulders.

"By the time I was sworn in I was just sort of like doubting everything. And at that point I just wanted to do the best job I could. Whatever that meant - and not particularly vote with any agenda or game in mind, even if that meant voting to make New Hampshire less free or in some sense."

Elizabeth is still outside what you might call the mainstream - she sponsored a bill to decriminalize sex work, for example. But on issues like climate change, she’s voting further along the progressive spectrum, and she’s not necessarily opposed to things like taxing carbon.

"All of my libertarian friends would be like, 'Are you crazy? Taxation is theft," she said. "They really don't understand."

Libertarians are tribal, she said, just like every other group, no matter how much importance they may place on the individual.

"If the Free State Project means that a lot of people who don't vaccinate their kids move here and it causes like outbreaks of vaccine preventable illnesses then deaths, then in that sense I definitely don't want the Free State Project to succeed."

Pushing back on the Free State

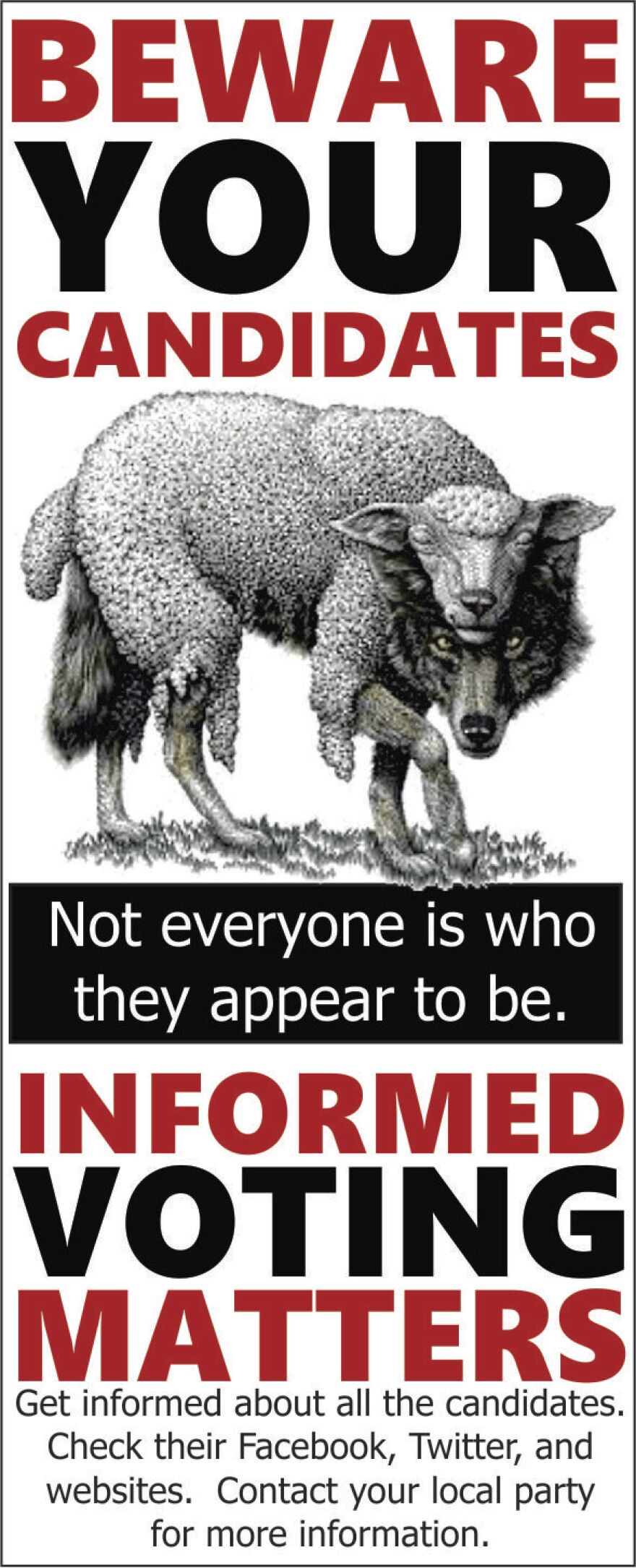

Zandra Rice Hawkins is Executive Director of Granite State Progress, which runs a website called Free State Project Watch. Every year, they put out a list of Free State Project candidates who are running for, and elected to office.

The logo on the website is a little red porcupine set over an image of New Hampshire. But the shadow of the porcupine, which stretches ominously upwards, reveals the black Halloween-esque silhouette of a fox.

It looks like a piece of Cold War propaganda, and in a way, Free State Project Watch has been waging a cold war against the FSP since 2009.

That’s because historically, FSP members running for office haven’t always divulged their Libertarian roots to the public - they just run as Republicans or Democrats.

New Hampshire has the biggest legislature in the country, and while that means state reps are accessible, it also means that it’s hard to research all of the candidates running for those offices. And some races go uncontested.

Zandra told me a story about two FSP candidates.

"He and his roommate were both running on the ballot. They flipped a coin. One ran as a Democrat, the other as a Republican, because they figured than a day one of them's going to get in office, which is what happened. And he was asked how he felt about public education and whether he would advocate for improvements to our roads and bridges and he said, 'I'm an anarchist. I don't believe there should be public schools or public roads.'"

This secret strategy of working inside the established parties rather than running as Libertarians - it actually goes all the way back to Jason Sorens’ original ideas about how the Free State Project could take over state politics.

If you live in New Hampshire and voted in a recent election, there's a chance you voted for a Free Stater without knowing it. That’s why Zandra says she's been “outing” FSP candidates for nearly a decade.

"What we ask is, 'Why did you move to New Hampshire? And if you moved because you signed a pledge to a political organization, and that is your sole purpose for moving here, then that doesn't leave a lot of room for us to have a gray area...you're either a member of the Free State Project or you're not.'"

It’s a question that rubs Carla Gericke the wrong way, which isn’t surprising. Carla stepped down from the Free State Project in 2016 and is now running for state senate for the second time.

"It seems very McCarthey-esque," she told me. "I mean, I could break down the Democratic Party into all kinds of little nuanced groups...maybe I'll send out a thing that asks, you know, 'Are you a socialist?'"

In addition to running for state Senate, Carla is now heading the Foundation for New Hampshire Independence. Their mission is to “educate citizens on the benefits of the Live Free or Die state peacefully declaring its independence and separating from the federal government of the United States.”

Zandra doesn’t care about the non-aggression principle, nor some of the other ideals embraced by the FSP. To her, the group will never shed its origin story: the Free State Project was started in an effort to secede.

"I give a lot of credit to the FSP for being so organized…but it does terrify me what their end goal is," she said.

Liberty? Anarchy? Or Party?

When the Libertarian Party was still brand new, there was a convention in Dallas, Texas.

The party was threatening to split, with a minority of members wanting to go full-on anarchy in the platform language, and the majority arguing that was political suicide.

'There's no utopia at the end of the tunnel...All we can hope to do is stimulate conversation and hopefully make the state a better place.' - Jason Sorens, founder of the Free State Project

This story shows that even for a third party, unrestricted by conventional politics, there is this question: Where do we compromise our ideals in exchange for a shot at success?

With the Free State Project, Jason Sorens seems to have done the impossible, convening a group of people who can have both.

Since they triggered the move, the mainstream media outlets haven’t had much reason to pay attention to the Free State Project. But one by one, Free Staters are continuing to move to New Hampshire, and the biggest changes are likely yet to come, even if some, like Elizabeth Edwards, are already finding a new ideology to follow.

"There’s no utopia at the end of the tunnel," Jason Sorens told me, "Which we should have known at the beginning. That’s what it means. All we can hope to do is stimulate conversation and hopefully make the state a better place."

Some see the Free Staters as chaos-makers, and some see the project as echoing other classic immigrant stories.

Whatever the perception, the truth is that since the Free State Project's founding, New Hampshire has seen them infighting over political tactics, grappling with who should be allowed in their tent, and running smart campaigns that win.

And when you add all those things up? What you get, at least on paper, is something that doesn't sound much different from Democrats and Republicans.

Click here to listen to the Word of Mouth episode from which this story was excerpted.

Do you have a question about New Hampshire or some quirk of your community? Submit it here at our Only in New Hampshire project page, and we could be in touch for a future story.

Correction: A previous version of this article claimed that Carla Gericke went to high school in Johannesburg, South Africa. In fact, she attended school in Pretoria.

In addition, the article claimed that Carla moved to the United States with her boyfriend. This was incorrect - she moved with her husband.

This post was further updated to clarify that Jason Sorens is a lecturer in the Department of Government at Dartmouth College, and that Ian Freeman legally changed his name in 2013.